International Competition: Dry Futures

Result: Honorable Mention (16 total selections/387 entries)

Jury: Allison Arieff, Charles Andersen, Colleen Tuite, Ian Quate, Geoff Managua, Hadley Arnold, Peter Arnold, Jay Famiglietti, Peter Zellner

Designers: Ian Caine, Derek Hoeferlin

Team: Emily Chen, Tiffin Thompson, Pablo Chavez

Date: 2015

Competition Brief

California – and much of the Western United States – is currently in the midst of a severe and unprecedented water crisis. After four consecutive years of exceptional drought, Governor Jerry Brown issued an executive order earlier this year intended to limit water usage and preserve the few resources that remain. But many worry that the measures amount to “too little, too late.” And the stakes couldn’t be higher: not only is California the most populous state in the country, it is by far the largest agricultural producer. Built on centuries of questionable riparian practices and infrastructure, this agro-industrial behemoth not only consumes the majority of the state’s dwindling water reserves, but amounts to a significant chunk of the national and international economy.

WATER MAY VERY WELL END UP BEING THE DETERMINING ISSUE OF THE NEXT CENTURY.

According to many experts, the drought in California correlates to both unsustainable human practices and the larger product of unsustainable human activity: climate change. It is simply irresponsible to imagine that a solution will magically appear off the coasts or in the clouds or anywhere else. California is on the verge of collapse. And for millions around the world – from Syria to Brazil – drought is already a determining factor in everyday life, creating conflict and reorganizing social relations.

While the practice of architecture may have not traditionally taken the primary role in determining how water is used, today, we no longer have a choice. Water is not only a fundamental precondition for dwelling, but the manner in which we choose to build (or not) is pivotal to the future viability of entire regions of the world. Water may very well end up being the determining issue of the next century. Yet, increasingly, it feels that the discourse of the “smart city” has overtaken all considerations of the future of architecture. How will ecological crises and technological advancement cohabitate the same future?

Archinect is launching a new competition oriented around the unfolding drought crisis in California. We believe architects possess a remarkable set of tools and skills that uniquely establish the capacity to adapt to a problem that is both multifaceted and enormous. We are looking for the imaginative, the pragmatic, the idealist, and the dystopian.

Competition Submission

The drought crisis in California is first and foremost a political crisis. Decades of public policy have created a system of massive water conveyance, fostering and maintaining a fundamental misalignment between the supply and demand of water. The untenable status quo in California is maintained through an elaborate slew of public policies, designed to support a system of water-trading between western states in areas like the Colorado River Basin.

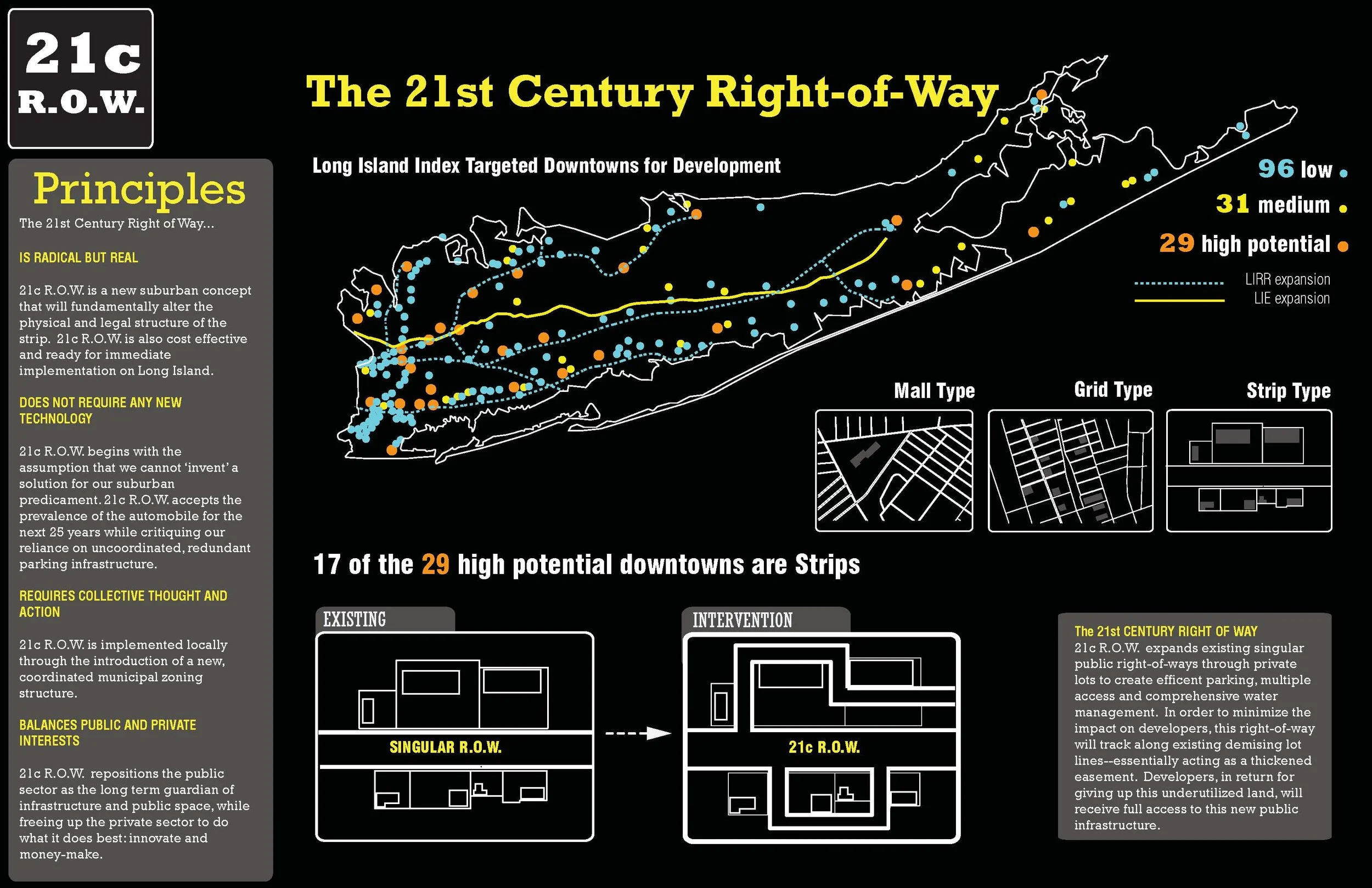

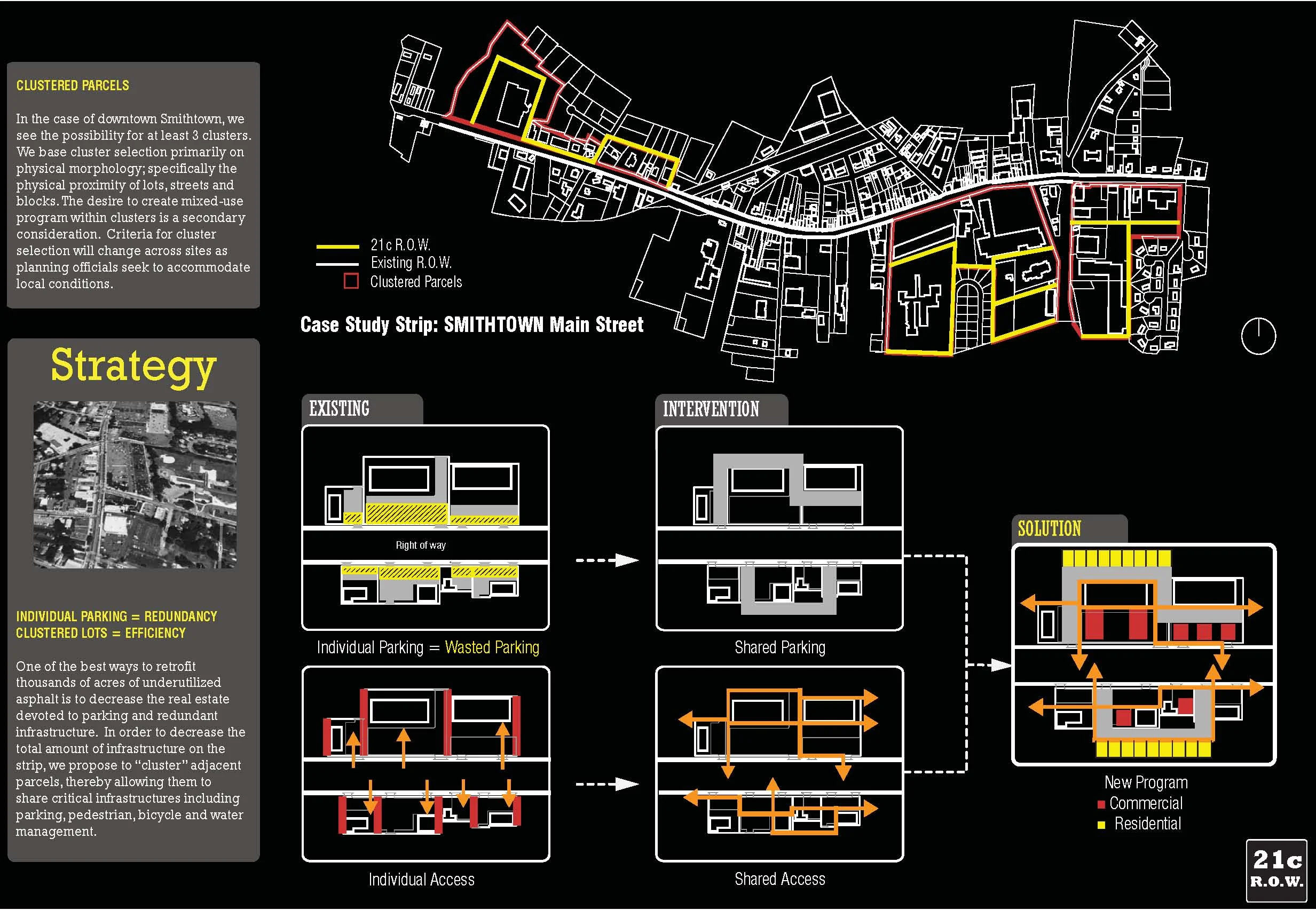

The Continental Compact proposes to fundamentally alter the culture of water-trading: re-legislating water distribution, first in California and ultimately throughout the United States, Canada and Mexico. The new laws will be based on four principles: Don’t transfer water. Do guide population growth to water. Do allow regions to shrink by attrition. Do return the river to its natural course.

California has maintained itself through an elaborate mechanism of water conveyance via aqueducts for decades. Unfortunately, the financial and environmental costs of this strategy are high. Currently the financial costs are being borne by the State and Federal governments, while the environmental costs are simply externalized, thereby delaying and intensifying their impact. This is an infrastructural shell game that California cannot win.

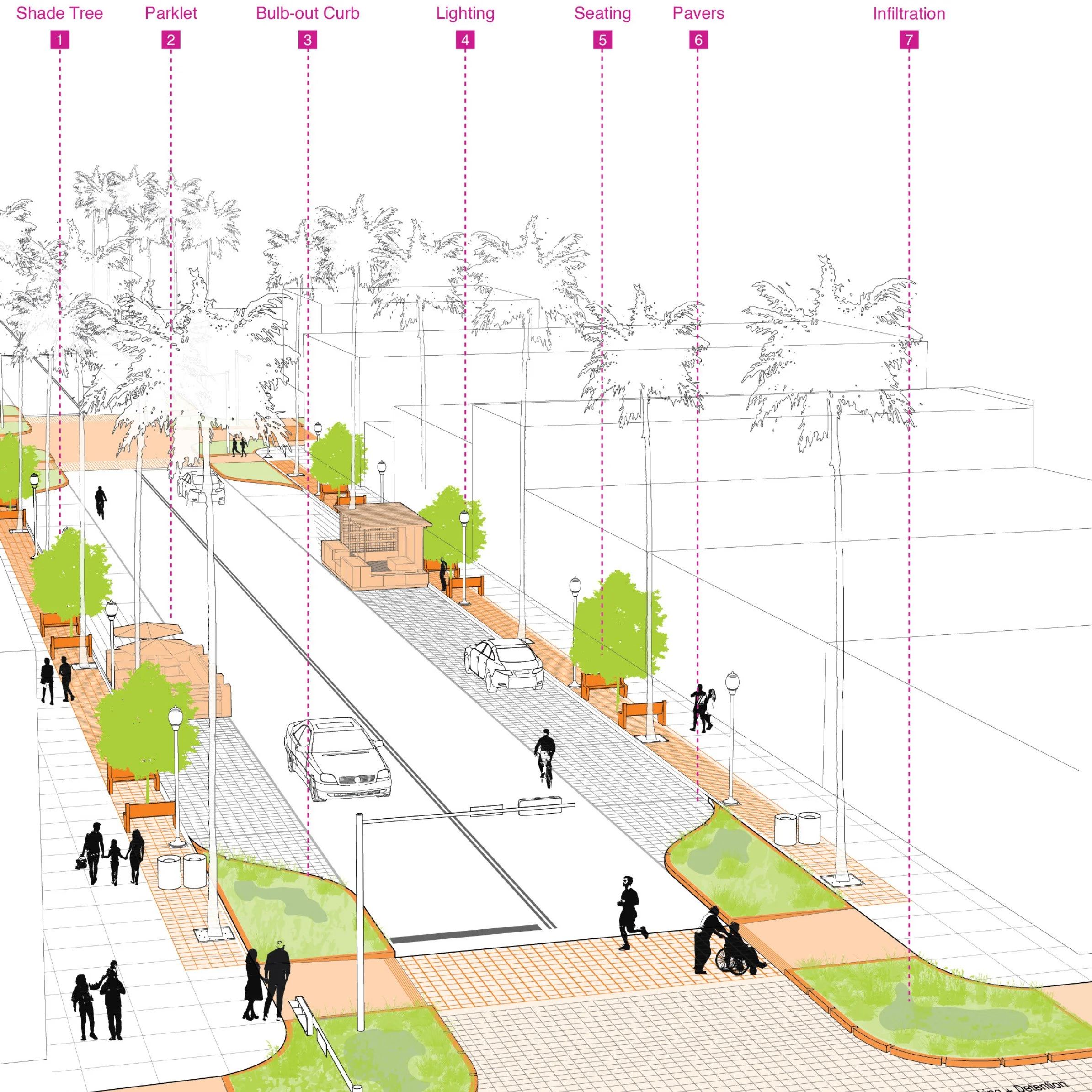

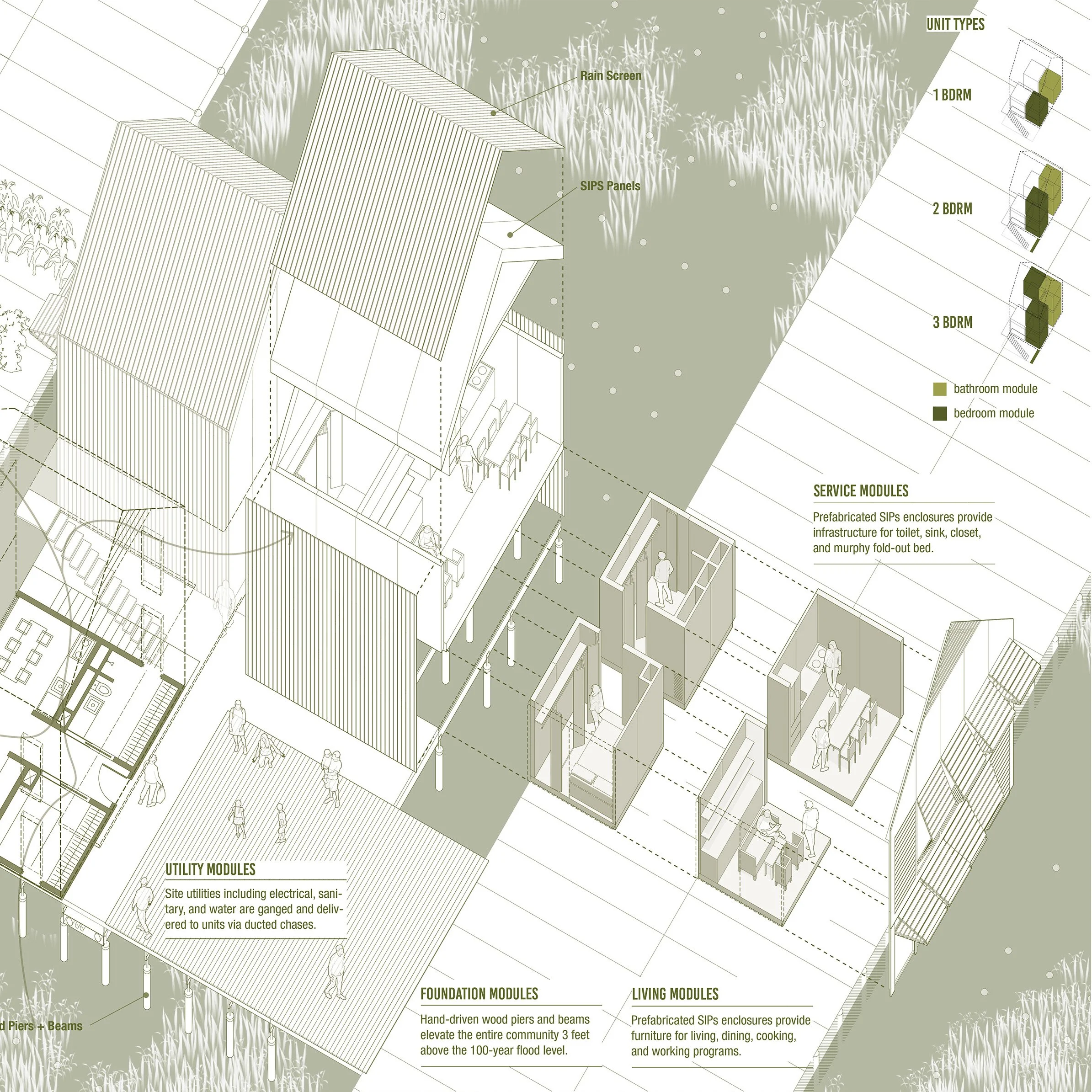

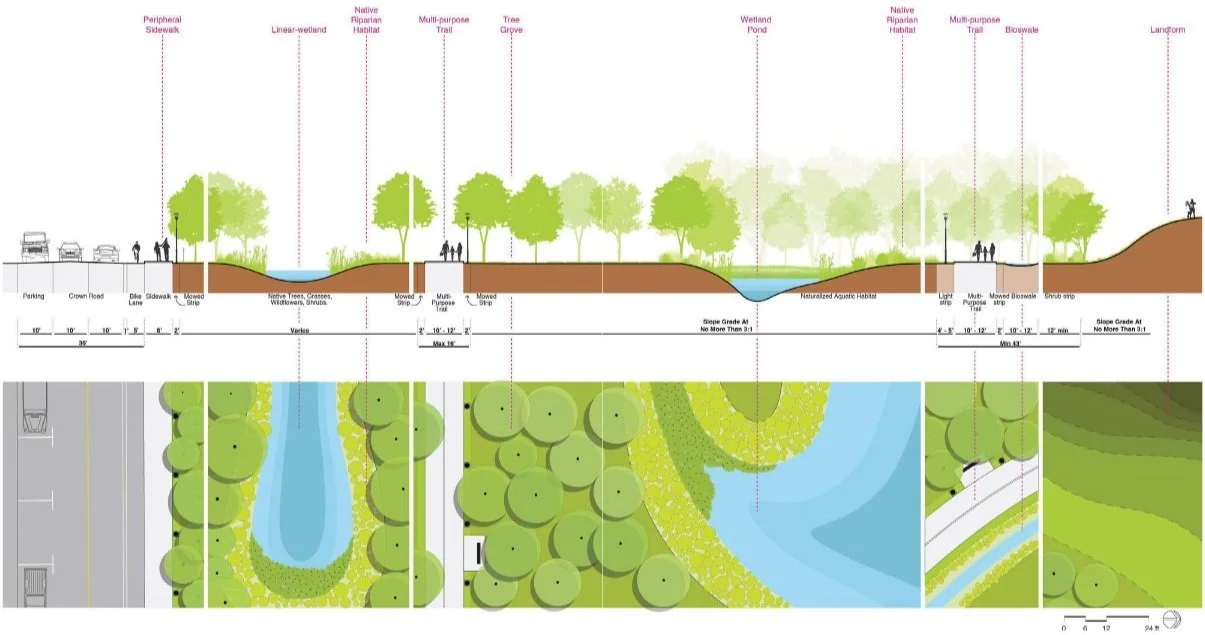

The Continental Compact provides a long-term solution to the contradiction that is California, incentivizing urbanism in water-rich basins near dams, rivers and deltas. The 3 types of hydro-urbanisms leverage existing water resources to create a conurbation at the scale of the river basin. Locally, each responds to the specific characteristics of its riverine, geographic and landscape environment. The hydro-urbanisms are capable of accommodating diverse programs including agriculture, residential, ecology, industry, recreation and tourism.

The Continental Compact replaces hydraulic urbanism with hydrological urbanism. Simply put, the Continental Compact stops moving water to the people and starts moving people to the water. The Continental Compact incentivizes a series of Hydro-regions, each leveraging a piece of new infrastructure in an existing water basin. The resulting megalopolis allows new water-rich urbanism to grow over a period of one hundred years. Conversely, it allows existing water-poor urbanism in Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, Phoenix, and Denver to slowly shrink via attrition. The positive environmental and financial benefits of the revised policy will be significant, saving energy, reducing carbon emissions, slowing subsidence, lowering infrastructure costs, and regenerating California’s deltas.

The history of Westward Expansion in the United States was an epic success, leveraging cheap land and abundant natural resources to grow the country. Things are very different today: land is expensive, resources are scarce, and state and federal governments are increasingly unable to afford the spiraling price tag associated with infrastructural obligations.

Current 2050 growth projections in the U.S. don’t factor what will likely become the most critical determinant of successful urbanism: water supply. The Continental Compact re-directs growth from Mega-regions to Hydro-regions, investing in water-rich urban conurbations built around dams, rivers and deltas. The Compact re-invests the massive resources that currently support the construction and operation of aqueducts into the construction of new infrastructure to support water-rich sustainable urbanism.

Images: Architect (cover), remainder of images by Ian Caine and Derek Hoeferlin