Edge City Redux: Las Colinas and the Fourth Wave of American Suburbia

University: UTSA

Level: Undergraduate

Student Projects: Antonio Chapman, Zach Maes, Matthew Gloria

Summary:

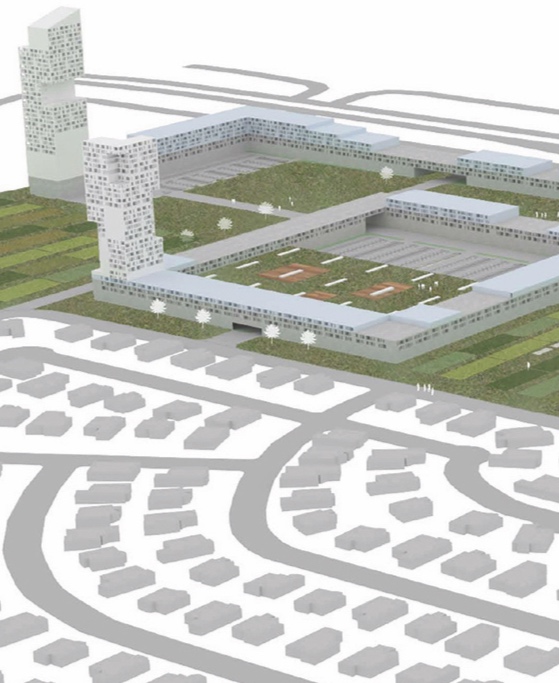

The Edge City in history. In 1991, author Joel Garreau introduced a new type of suburban place to the United States: the Edge City. While the term was new, the Edge City itself needed no introduction. In fact, U.S. developers had been building these places for decades. As Garreau explained, Edge Cities represented the third wave of postwar suburban development in the United States: in the first wave, people built homes outside of historic downtowns and commuted to work; in the second wave, after WWII, developers moved shopping centers to the suburbs to serve the new residential markets; and in the third wave, beginning in the 1960s, employers moved offices and industry to the suburbs so that people would not have to commute to work. The third wave represented the advent of the Edge City phenomenon that remains so prevalent in U.S. cities today. This advanced undergraduate studio will reconsider the twentieth century Edge City phenomenon within the contemporary Texas context, asking several critical questions:

First, what is the state of first-generation Edge Cities today, fifty years after their emergence? How can we assess their economic, social, environmental, and architectural success?

Second, what possibilities exist to retrofit, renovate, or reimagine these environments? Could the retrofit of an Edge City like Las Colinas represent a fourth wave for American suburbia? If so, what would this look like?

This studio proceeds on the assumption that in order to fundamentally transform the social, spatial, environmental, and programmatic trajectory of urban growth in the United States, we have to fix Edge Cities. We know that 75% of new construction takes place in the suburbs, which means that if designers are to help shape the character of the next American city, we must address the large-scale deficiencies--and opportunities--that exist in suburban environments. The site for our work will be the Texas Triangle, a megaregion that includes five of the ten fastest growing large cities in the U.S.: Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, Houston, and Austin (United States Census Bureau). We will specifically travel to the fourth largest metropolitan area in the United States, the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, to investigate Las Colinas, an early Edge City development in the United States that is now failing across a number of ecological, financial, and urban criteria.

This studio will provide students with an opportunity to

1. investigate contemporary urban design issues within the context of a fast-growing North American city

2. use drawing to generate clear and formally powerful urban design proposals

3. practice designing across multiple scales from the site to the building to the unit

4. acquire mapping techniques capable of analyzing urban context with precision and breadth

5. study contemporary housing typologies and learn how to re-apply them in a suburban context

6. generate urban strategies to intensify the civic realm within dispersed, polycentric growth patterns

7. leverage the synergies that exist at the intersection of infrastructure, program, and urban form

8. develop a systems-based approach to design

Metropolitan and regional context

Growth, and more growth. Founded in 1841, Dallas began to emerge as a major financial and freight center with the discovery of oil in the 1930s. Today, Dallas is home to twenty-two Fortune 500 companies, which is five more than London and just two less than New York. Each month, Dallas-Fort Worth adds 12,000 people to its population, making it the second-fastest growing metropolitan area in the U.S., trailing only Houston. Current estimates indicate that the metropolitan area will absorb 3.8 million more residents by the year 2040, a 54% increase that will swell the overall population from 7.1 to 10.9 million residents. Where will all of these people live, shop, and work? How will they move through the city? And most importantly, what will be the quality and character of the urban landscapes that they inhabit?

The site

Las Colinas. The specific site for our work this semester is Las Colinas, an Edge City site that lies ten miles northwest of downtown Dallas. The project, founded in 1972 by millionaire cattle rancher and developer Ben Carpenter, began with great promise: it was one of the largest master planned communities in the South and initially attracted the global headquarters of four Fortune 500 companies. Much of its initial popularity was due to the development’s close proximity to an international airport. Las Colinas added another 6.5 million square feet during the 1990s and today is home to more than 2000 companies.

In recent years, however, neighboring Edge Cities like Frisco, Addison Circle, and Legacy have surpassed Las Colinas as prime destinations for new development. This is not surprising, as Las Colinas suffers from the same shortcomings that plague similar first generation Edge City developments: a lack of mixed-use programming, civic space, walkability, sense of place, and diversity of housing options. International urban planning firm Sasaki recently produced a new master plan that aims to overcome the development’s poor urban image, create a sense of destination, and diversify land use. The prospects for the success of Sasaki’s redevelopment plan are not clear.

The dissolving distinctions between urban, suburban, and exurban form. As cities expand and suburbanize, traditional distinctions between urban, suburban, and exurban landscapes continue to dissolve, making established programs and forms increasingly obsolete. Architect Judith DeJong writes:

“The ongoing flattening of the American metropolis is increasingly visible through the proliferation of hybrid sub/urban practices...each of these practices not only evinces new forms from reciprocating urban and suburban influences, but also provides a key point of departure for the articulation of new ways of forming the evolving American metropolis…”

As a response to this increasingly fluid situation, the studio will generate new spatial and programmatic arrangements for the Edge City of Las Colinas. This will mean proposing redevelopment scenarios that introduces spatial compactness, programmatic diversity, residential density, and connectivity to existing fabric. This will require designers to confront a series of complex questions: What possibilities exist to hybridize programs? Can we develop new housing typologies capable of interfacing with these new programmatic arrangements? What infrastructural strategies can increase connectivity both within emerging nodes and with adjacent urban fabric?

The studio will act on the assumption that currently, architects and urban designers lack clear and tested answers to these critical questions.

Traveling on Fredericksburg Road: 120 Years in 12 Miles

University: UTSA

Type: Seminar

Level: Graduate

Students: Xuhua Cheng (Research Assistant and Exhibit Designer), Emi Furuya (Research Assistant and Exhibit Designer), Raul Montalvo (Research Assistant and Exhibit Designer), Peyvand Ali Amiri, Alvaro Espino, Raymond Flores, Marco Gonzalez, Braulio Hurtado, Britta Moe, Barry Reyna

Faculty Researcher and Exhibit Designer: Ian Caine, Assistant Professor, UTSA

Lead Curatorial Researcher for Exhibit: Dr. Sarah Gould, Institute of Texan Cultures

Introduction

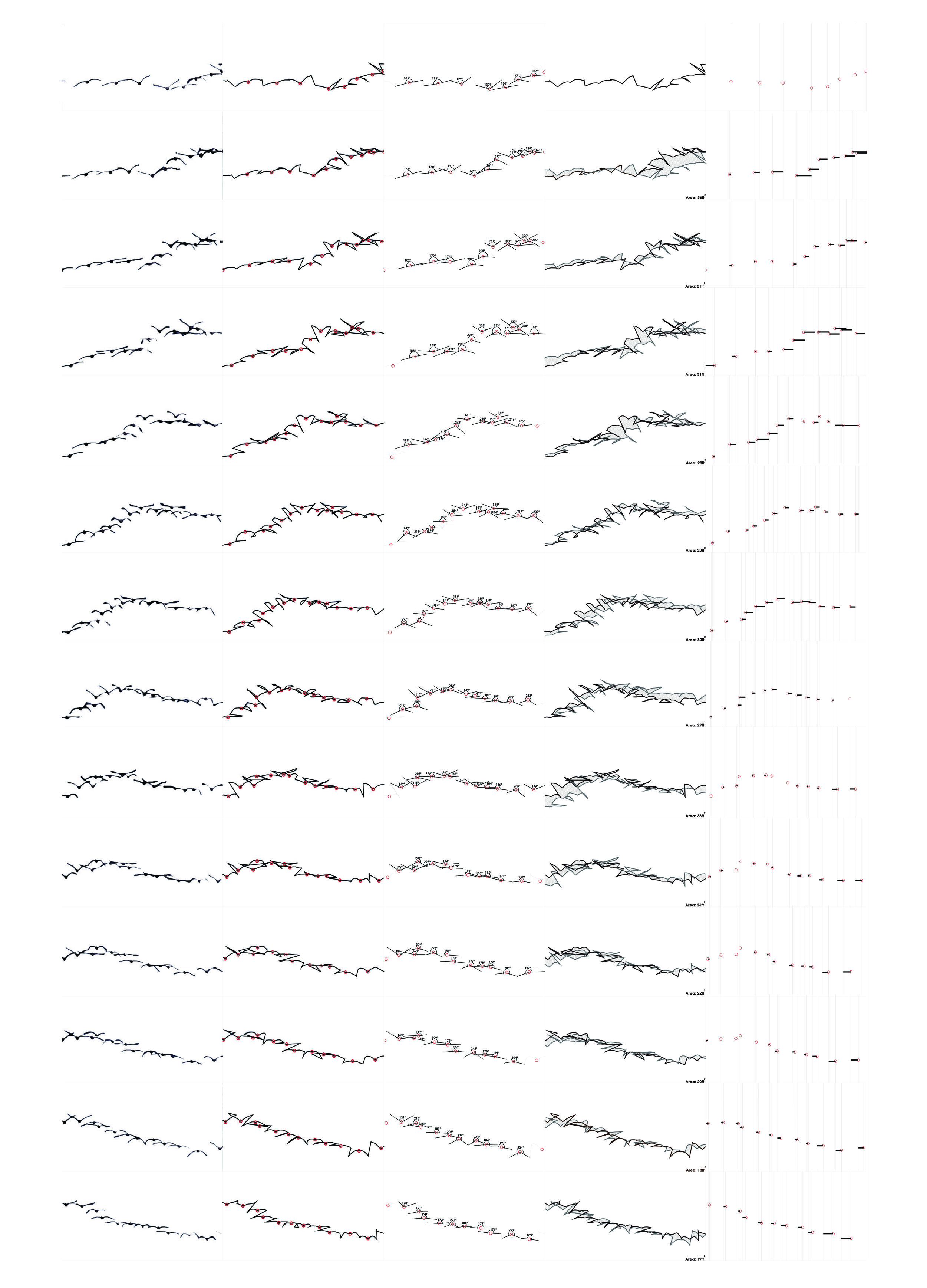

This seminar will investigate the historical foundations of North American suburbia by studying the life of a single street: Fredericksburg Road in San Antonio, Texas. Fredericksburg Road, founded in the 1840s as a military route to the frontier, has served a number of purposes throughout the years: as a camel route for the Army in 1855, as a path for troops during WWI, as an automotive link to the Old Spanish Trail highway in 1929 and most recently as one of the most travelled commercial arterials in the city [1]. For the purposes of this class, Fredericksburg Road will serve as a physical timeline that chronicles the physical expansion of San Antonio, one of the ten fastest growing cities in the United States [2].

The class will utilize morphological analysis in an attempt to gain a better understanding of urban decentralization as both a universal phenomenon and a local condition. In order to accomplish this goal the course will proceed on two parallel tracks: First, the instructor will provide historical background on the prevailing economic, political and social forces that led to the decentralization of the North American city. Students will simultaneously engage key readings in support of these lectures. The lectures and readings will provide a conceptual framework for the analytical portion of the class. Second, students will generate a series of graphic transects through Fredericksburg Road as a method to develop a series of morphological snapshots that track the street’s development. The class will map and analyze these sections in an attempt to understand the relationship between Frederickburg’s physical progression and larger economic, political and social forces.

This seminar will result in the production of a single, large-scale graphic timeline suitable for museum display. The instructor is currently arranging for the funding and installation of an exhibition in San Antonio during the fall of 2013. Both Architecture and Planning students with graphic backgrounds are encouraged to enroll in the class and participate in this project.

Topics for analysis will include buildings, lots, setbacks, ownership, occupation, demographics, commerce, investment, roads, sidewalks, parking, program, zoning, transportation, infrastructure, public space and natural systems. The class will provide basic GIS instruction so that students can utilize the software to generate data necessary for morphological analysis. The class will require reading, drawing and a commitment to teamwork; no papers or examinations will be involved.

Learning Objectives

This seminar will offer students the opportunity to deepen their understanding of North American urban trends while developing a significant piece of original scholarship through the intense examination of local conditions.

Learning Outcomes

Students will produce one large scale two-dimensional timeline that chronicles the physical development of Fredericksburg Road. The timeline will be publicly displayed at the end of the Spring 2013 semester and again during the Fall of 2013.

Special Thanks

Mitchell Andry, Cool Crest Miniature Golf Course

Linda DeWese, De Wese’s Tip Top Café

William Dupont, Director, Center for Cultural Sustainability, UTSA

Dr. John Frederick, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, UTSA

Andrew and John Garcia, Garcia’s Restaurant

Dr. Sarah Gould, Lead Curatorial Researcher, Institute of Texan Cultures

Claudia Guerra, Program Coordinator, Center for Cultural Sustainability, UTSA

Charlotte Kahl, Chair, OST 100

Martin Rodriguez, Senior Information Technology Associate, UTSA

Madeline Slay, Madeline Anz Slay Architecture, PLLC

Dr. Richard Tangum, Professor, Director, Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research,UTSA

Dr. Anne Toxey, Visiting Researcher, Center for Cultural Sustainability, UTSA

Jacob Valenzuela, Deco Pizzeria

Christine Viña, Project Manager-Urban Design, VIA Metropolitan Transit

Institute of Texan Cultures

UTSA Center for Cultural Sustainability

UTSA Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research

UTSA College of Architecture

[1] David Green. Place Names of San Antonio. (San Antonio: Maverick Publishing Co, 2002), 23.

[2] Fisher, Daniel, “America’s Fastest Growing Cities.” Forbes 18 (April 2012).

Produced by Dr. Sarah Gould

Theorizing Sprawl I

University: UTSA

Type: Seminar

Level: Undergraduate and Graduate

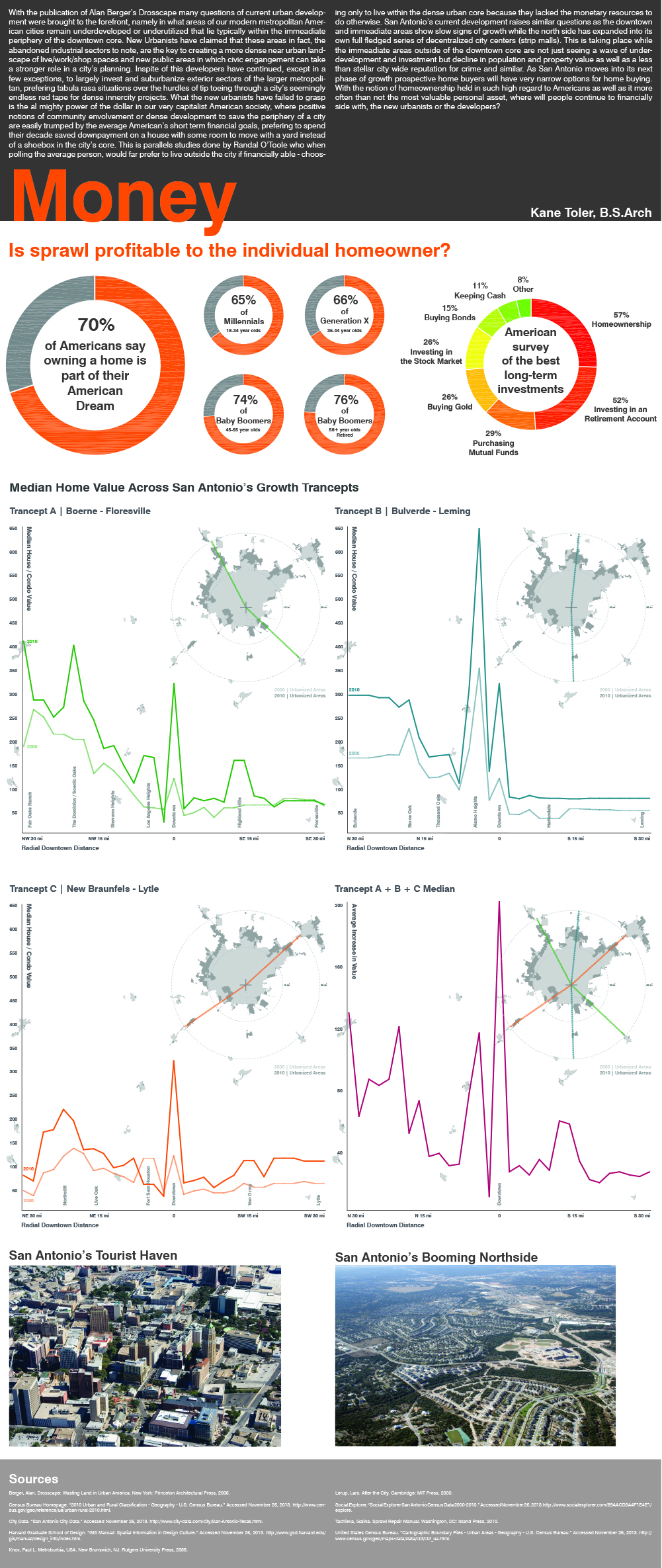

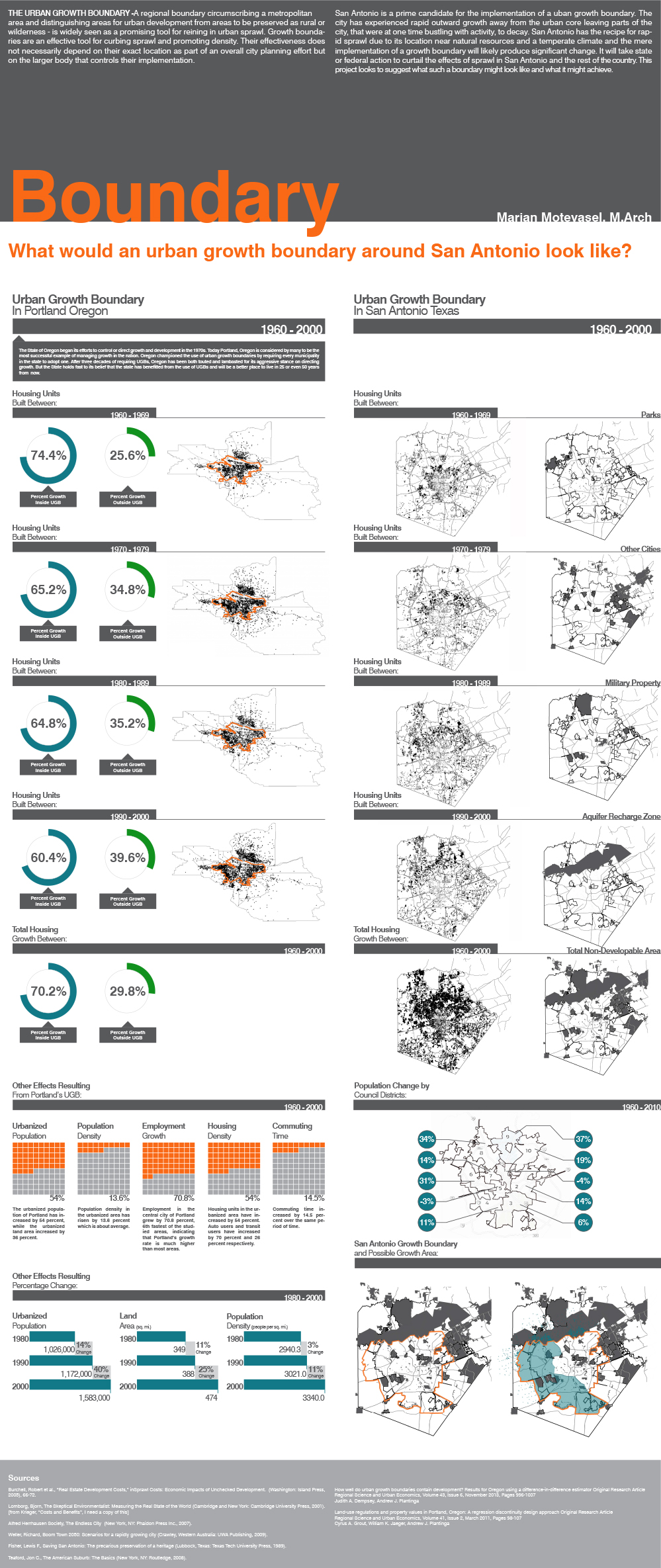

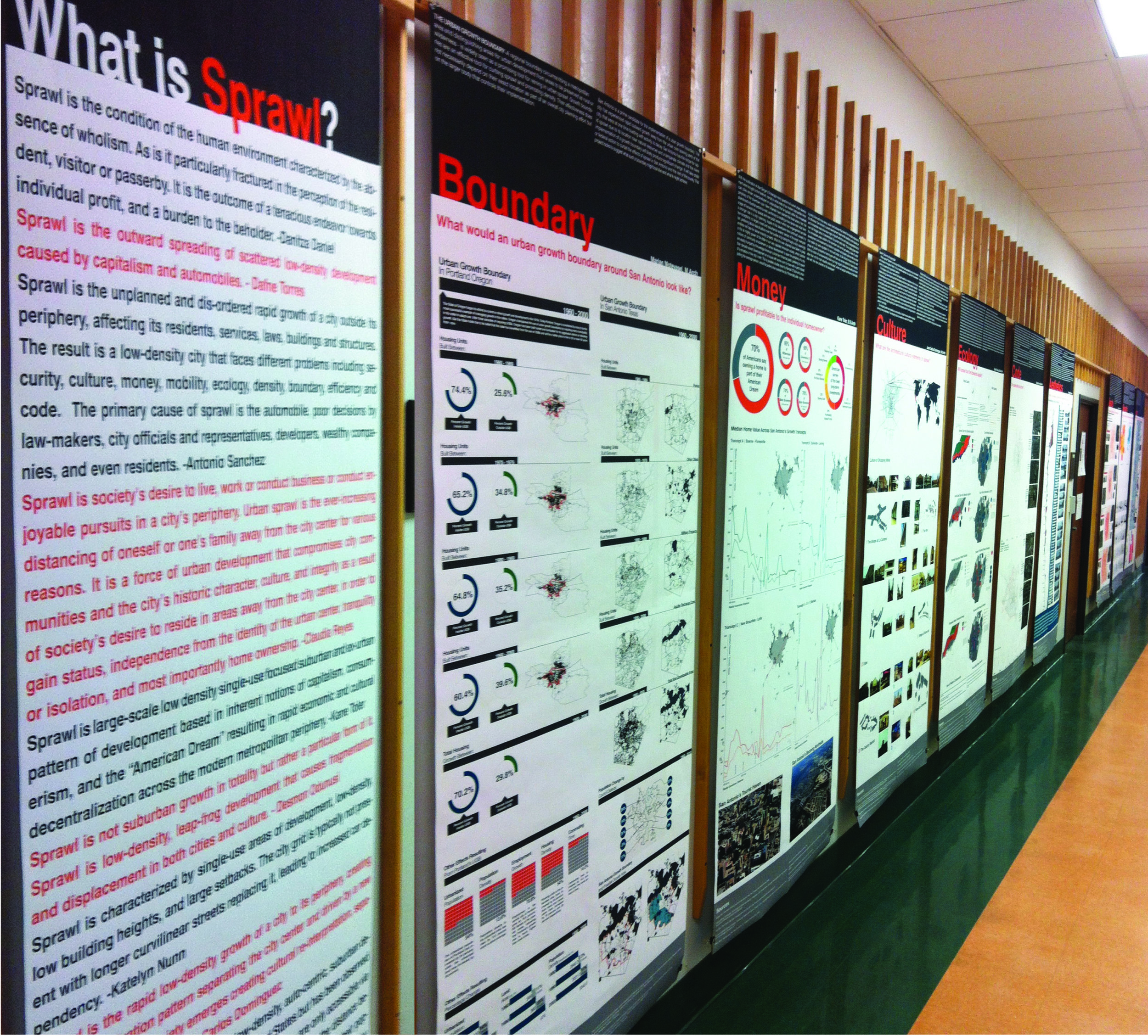

Student Projects: Sima Jolghazi (Form), Brandon Turriff (Boundary), Daphne Torres (Ecology), Kane Toler (Money), Marjan Motevasel (Boundary), Group Exhibition

Summary

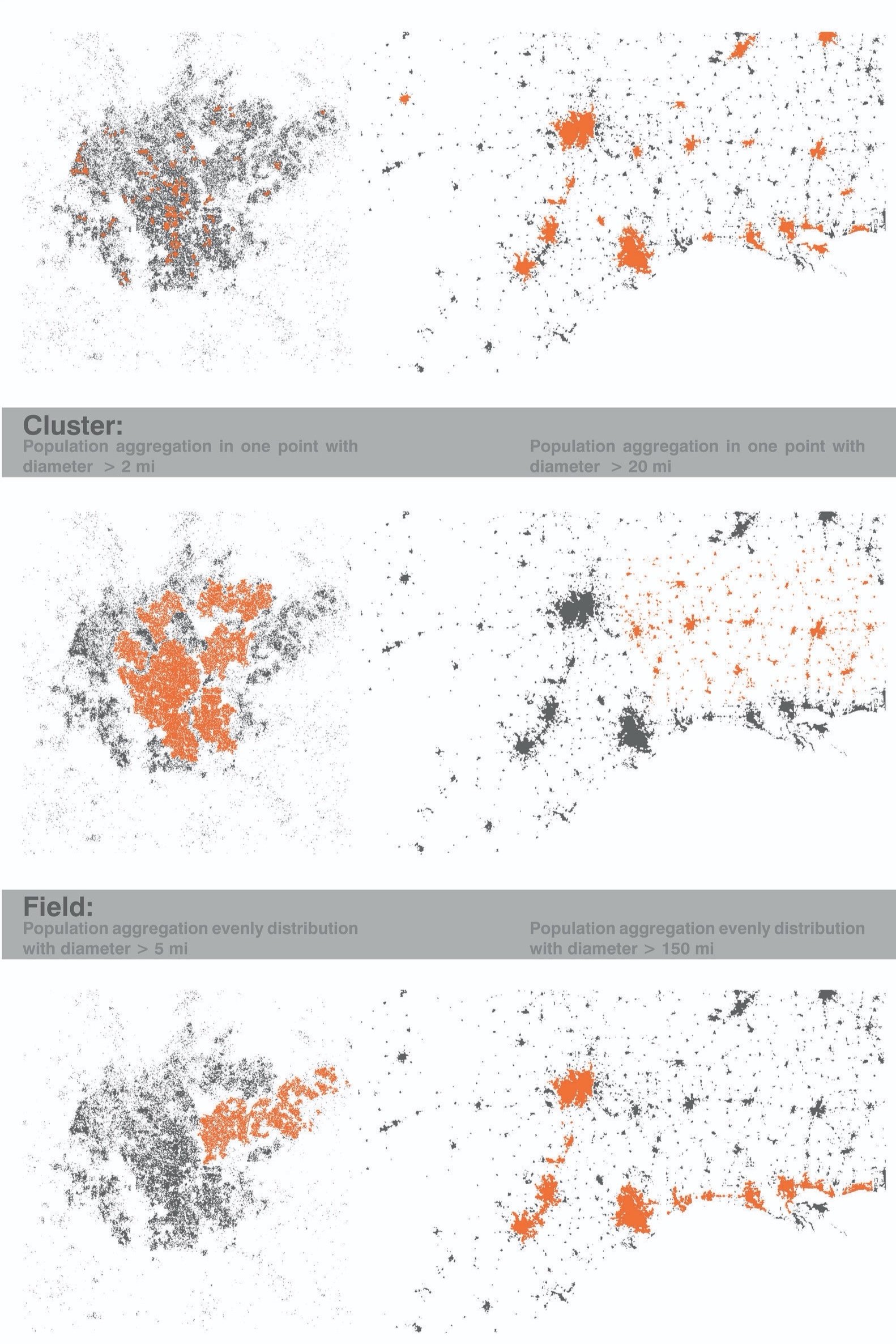

Sprawl is perhaps the most objectionable term in today’s urban lexicon. A wide range of urban actors including policy-makers, planners, public health officials, and designers routinely blame sprawl for the most intractable urban problems. The prevailing sprawl narrative explains that a range of urban challenges from pollution to poor health, cultural dislocation to commute times, will be solved with a return to the compact city. Is this diagnosis accurate? Are we correct to attribute such a wide array of liabilities to a phenomenon as specific as sprawl? If the answer is yes, is it even possible to reverse the prevailing trend towards urban decentralization? This seminar will re-position the sprawl narrative within an accurate theoretical and historical framework. In doing so, the class will pursue answers to the following fundamental questions: What is the most useful working definition of sprawl? Are sprawl and suburbanization the same? When, where, and how has sprawl evolved? What are the verifiable health and environmental impacts of sprawl? What are the competing theories and evaluations of sprawl?

The advanced graduate seminar asks students to undertake one semester-long graphic-based/applied research project within the most critical emerging mega-region in North America: the Texas Triangle (Dallas, Houston, San Antonio). The seminar is structured around the following themes:

Week 01 What is Sprawl?

Week 02 GIS Training

Week 03 Form

Week 04 Aesthetics

Week 05 Culture

Week 06 Security

Week 07 Mobility

Week 08 Ecology

Week 09 Infrastructure

Week 10 Money

Week 11 Density

Week 12 Boundary

Week 13 Region

Week 14 Exhibition

Background

During the first two decades after WWII the population of the United States rocketed from 150 to 200 million people, an unprecedented demographic explosion that revolutionized the nation’s social landscape and gave rise to the great American middle class. The demographic growth also catalyzed a radical reconfiguration of the physical landscape, transforming cities from continuous grid-based configurations composed of blocks and streets to intermittent spine-based systems comprised of highways and culs-de-sac [1]. This massive shift revolutionized the form of U.S. cities and gave rise to the uncoordinated, scattered, and decentralized landscape that many now term sprawl.

The large-scale decentralization of U.S. cities prompted a fierce and divergent set of reactions from critics: early responders like Peter Blake railed furiously against the unwieldy turn of events, condemning the complicit actions of the federal government, developers, and others “…who have already befouled a large portion of this country for private gain….” [2]. Still others like Kevin Lynch and Robert Venturi came to embrace the emerging logic of decentralization, generating research programs that sought to establish terms for the new city. This philosophical split continues today, as observers like James Kunstler Howard and Andrés Duany cast the decentralized city as an anomaly, best corrected with a return to traditional urban morphologies. Others, like Lars Lerup and landscape architect James Corner, accept the prevailing terms of the new city, recommending a systemic reading of the diffuse terrain that de-emphasizes form and prioritizes ecology.

Urban history tells us that the origins of decentralization are multifaceted and extensive: throughout the early Christian period Rome saw the emergence of a suburbium that catered to travelers and programs that were not easily accommodated within the city walls; during the early 18th century gridded suburbs grew just beyond Berlin’s wall, accommodating growth that did not fit within the confines of the medieval city; in the early 19th century Brooklyn emerged as the first commuter suburb in the country, allowing wealthy residents of Manhattan to escape the industrial city after work; and late in the 19th century streetcar suburbs materialized at the perimeter of U.S. cities, the result of burgeoning streetcar lines. These diverse histories offer critical perspective on the complex challenges facing decentralizing cities like San Antonio, which between the years 2000-2010 emerged as one of the fastest growing and sprawling cites in the U.S. [3] [4]. The unrelenting expansion has transformed the physical landscape of San Antonio: the original 36 square mile grid--which bound the city as recently as 1922--has expanded ten-fold to 368 miles, while the metropolitan area now consumes 7371 square miles [5] [6]. At the regional scale, San Antonio represents one of three legs in the “Texas Triangle,” an expanding mega-region that will add another ten million people in the next four decades. These staggering numbers leave San Antonio and the surrounding region in a precarious balance: seduced by the spoils of growth while scrambling to evade ecological peril. The statistics also remind us that any legitimate discussion of urban futures in the United States will require us to establish a critical position regarding the ubiquitous condition of sprawl.

Learning Goals

1. This seminar will provide students with an opportunity to develop a historical and theoretical framework on the topic of sprawl, allowing them to develop informed opinions on the complex and contenious topic.

2. The seminar will help students develop the ability to read, evaluate, and develop their own theoretical positions related to the complex issue of sprawl.

3. This seminar will introduce students to the principles and methods of architectural research, particularly as they relate to the emerging multidisciplinary field of the spatial humanities.

Learning Outcomes

1. Students will complete a series of guided readings and participate in facilitated discussions covering theoretical and historical issues related to sprawl. The instructor will additionally provide a series of lectures covering history, definitions, and theory of sprawl.

2. Students will participate in weekly discussions, facilitated by the instructor.

3. Students will develop architectural research tools including text, data collection, field research, archival research, and mapping. Students will produce a semester-long research project related to the geographic and demographic expansion of the Texas Triangle. The class will exhibit this work at the end of the semester.

[1] Susan Rogers, “An Interview with Albert Pope,” Cite: The Architecture + Design Review of Houston 94 (Spring 2014): 9.

[2] Peter Blake, God’s Own Junkyard: The Planned Deterioration of America’s Landscape (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964), 7.

[3] Daniel Fisher, “America’s Fastest Growing Cities,” Forbes 18 (April 2012).

[4] “San Antonio among top cities for urban sprawl,” San Antonio Business Journal.

[5] “San Antonio Statistics,” San Antonio Chamber of Commerce.

[6] “San Antonio, New Braunfels Metro Area,” USA.com.

[7] Kent Butler et al. “Reinventing the Texas Triange: Solutions for Growing Challenges.” University of Texas at Austin: Center for Sustainable Development (2009): 14.

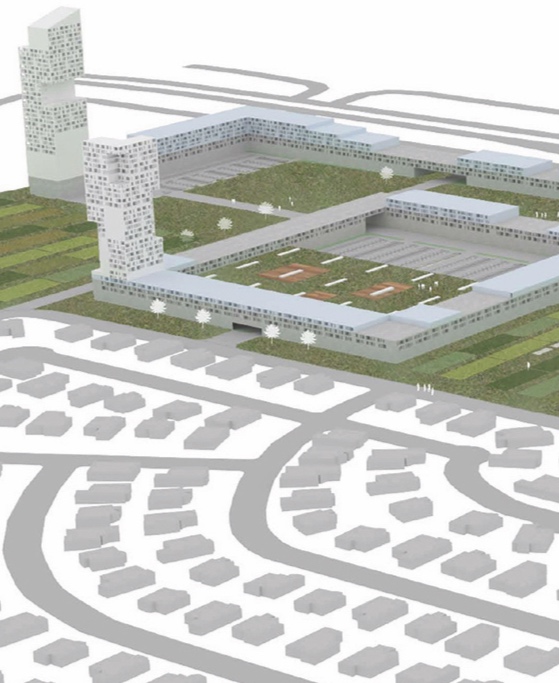

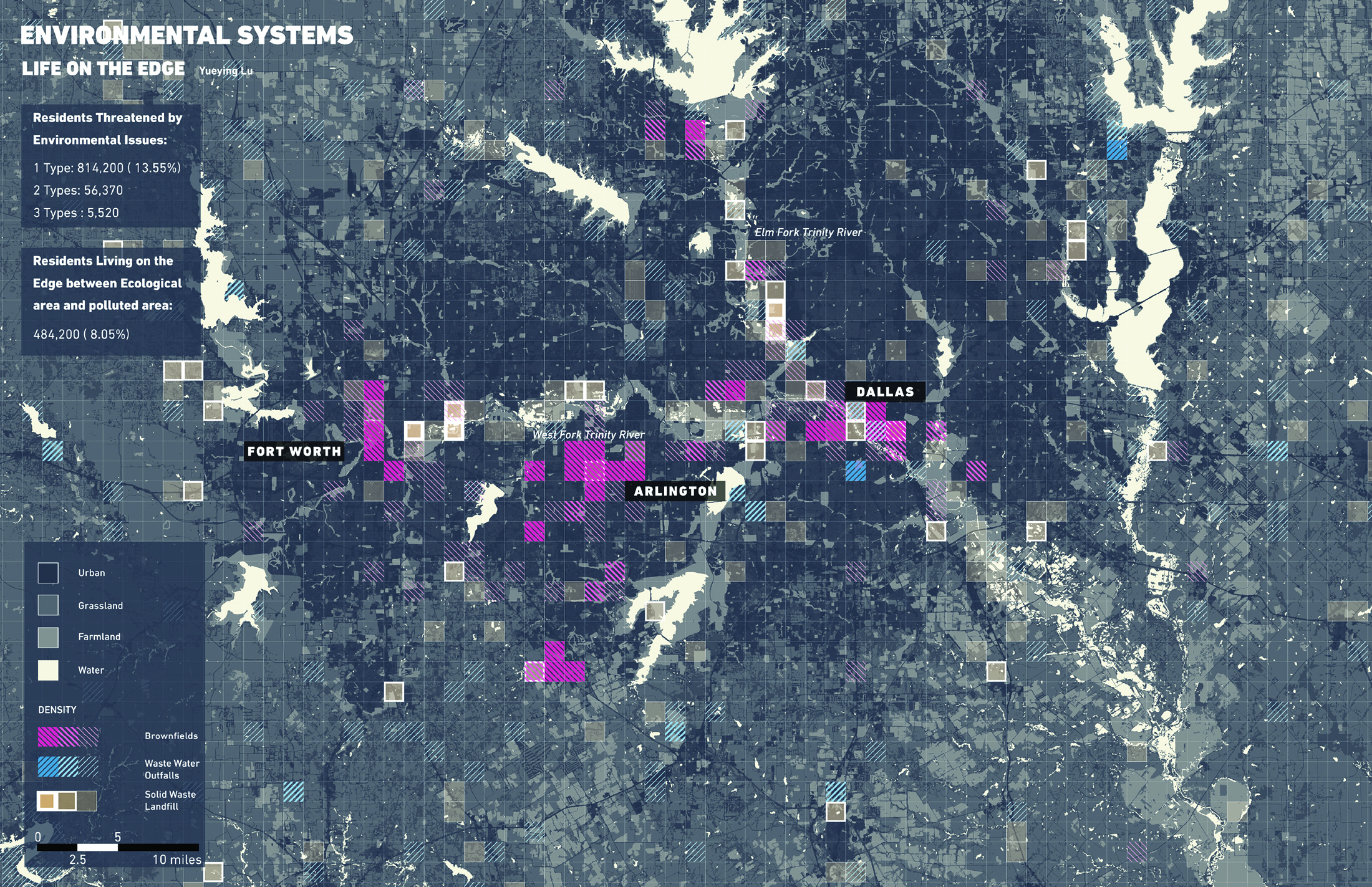

New Growth Strategies for the Polycentric City [Analysis]

University: Washington University

Type: Urban Design Studio

Level: First Year Master of Urban Design

Co-Instructor: Pablo Moyano

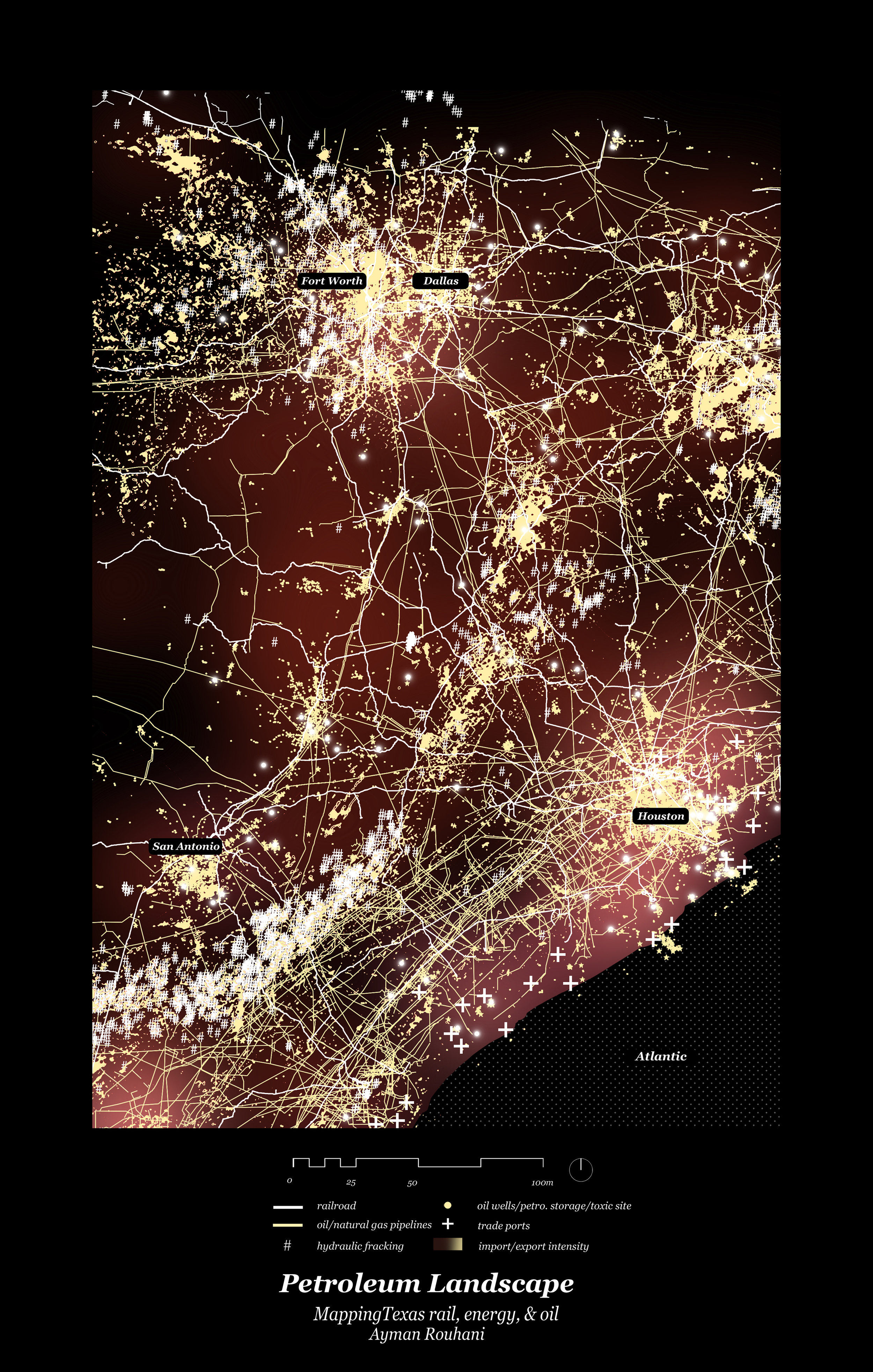

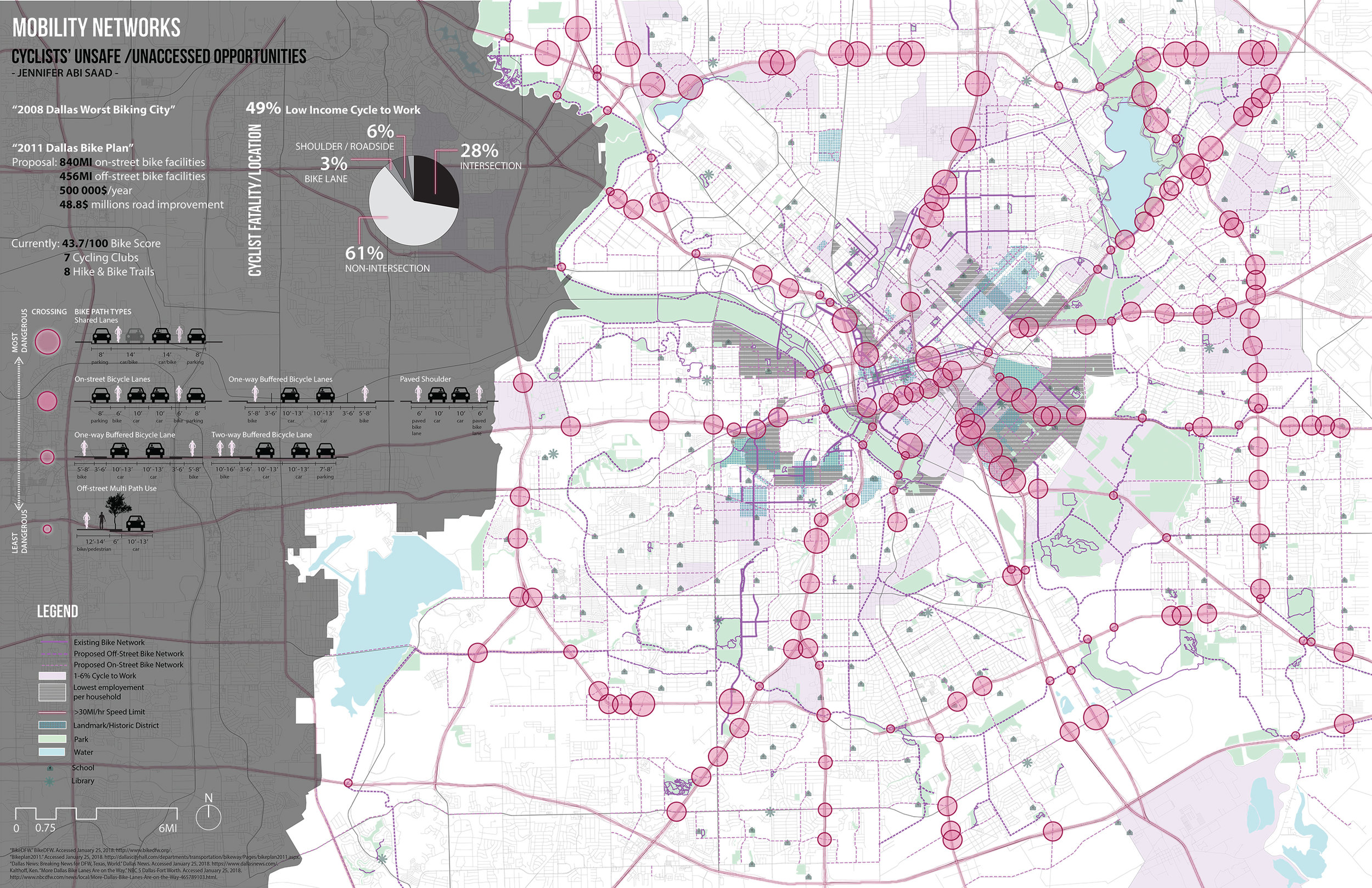

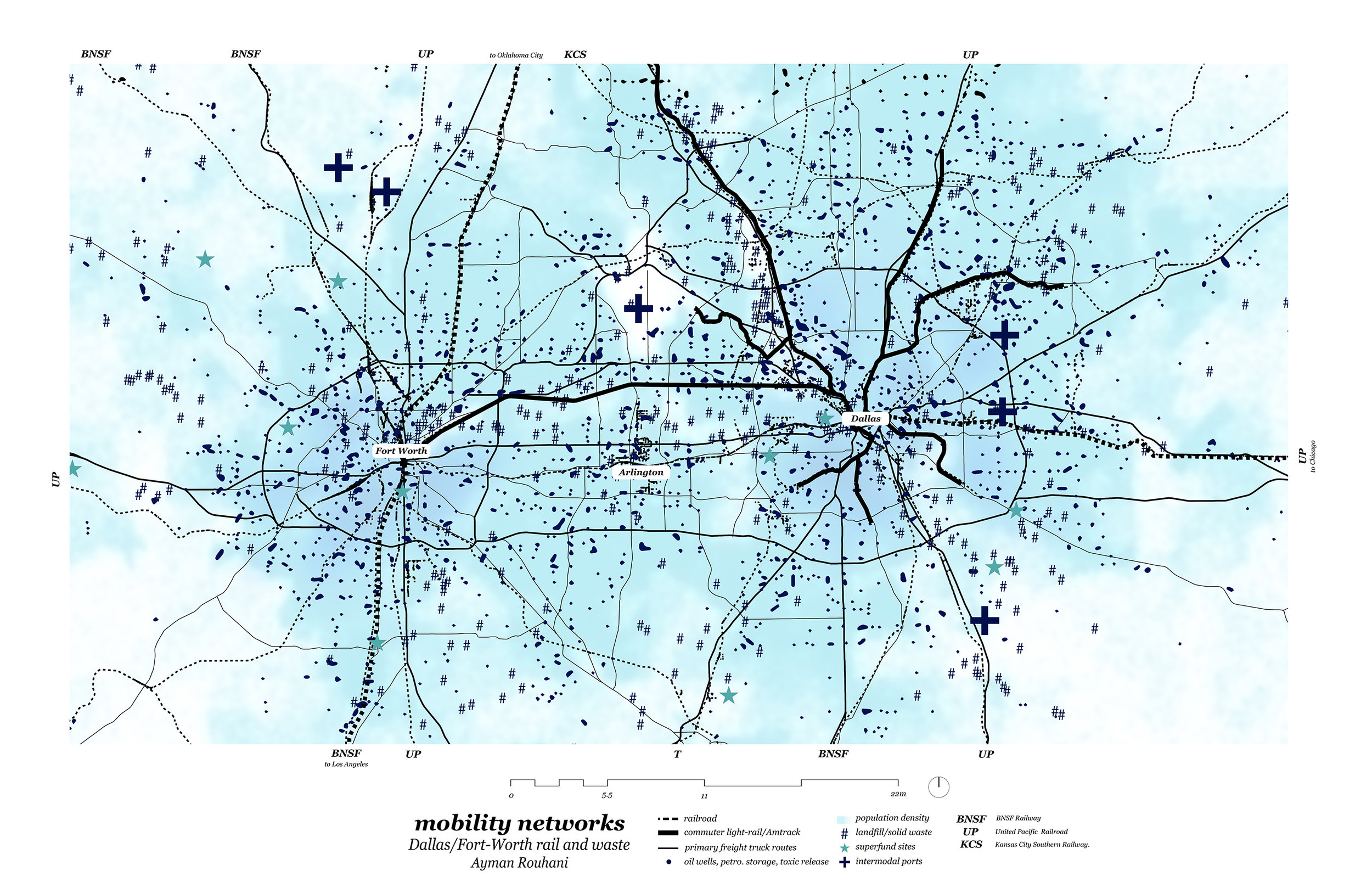

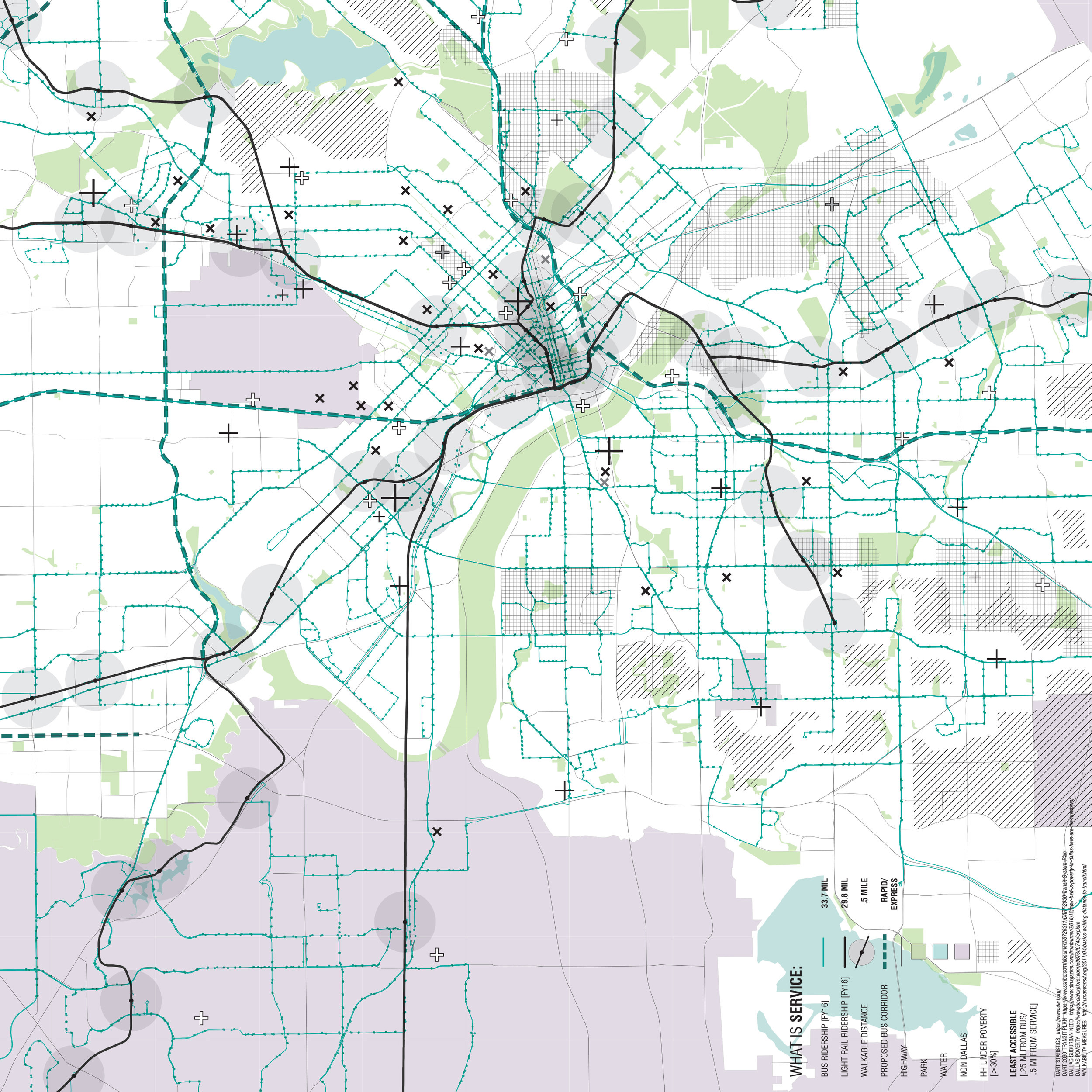

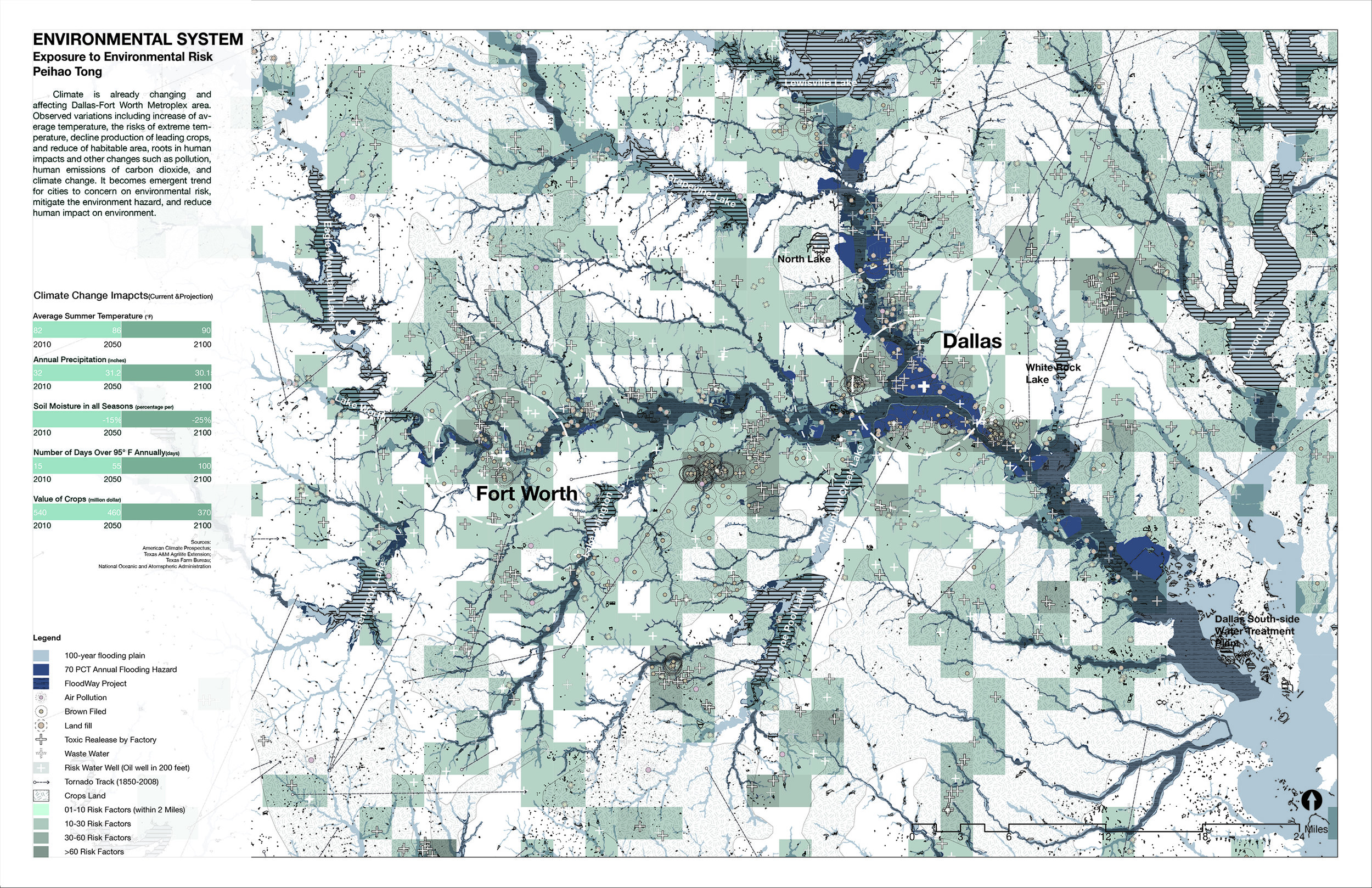

Student Designers: Yueying Lu, Ayman Rouhani, Jennifer Abi Saad, Christine Doherty, Ayman Rouhani, Peihao Tong, Yong Yuan

Exercise Duration: 1 week

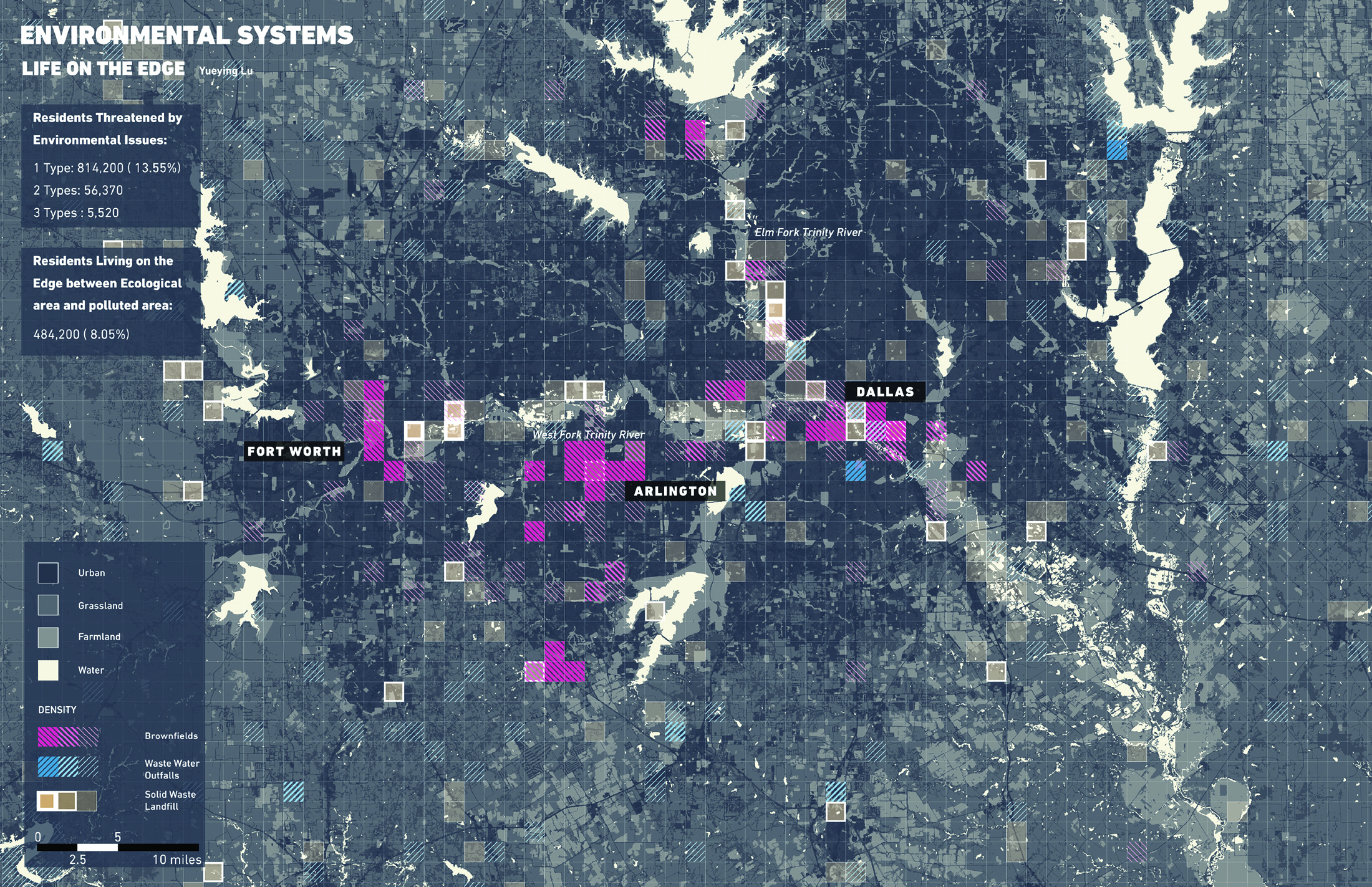

Summary

This exercise will prepare students for the design portion of the semester, introducing them to the essential urban systems and components of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex. Working at the metropolitan scale, students will explore the entire 13 county Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington MSA.

Each student will be responsible for completing a single, individual mapping exercise. Within each topic group, students will coordinate their research efforts to avoid redundancy, share data, and benefit from the collective insights of colleagues.

Students will begin by choosing one of the suggested subtopics, then identify, research, and map a CRITICAL RELATIONSHIP related to the topic. For example, if you are assigned ENVIRONMENTAL SYSTEMS, instead of simply mapping the watersheds, you might map watersheds v. flood events. Or if you are assigned MOBILITY NETWORKS, instead of mapping transit networks, you might map transit networks v. residential density. As you develop the mapping, consider well established categories of urban relationships, such as transit v. land use or infrastructure v. program.

The maps are intended to be speculative, rather than objective or neutral. So, the goal is to avoid simply redrawing informational layers, or making visual lists. Each student should seek to establish one or a series of critical relationships within the existing urban structure, while establishing relevant opportunities and constraints to guide the semester’s work.

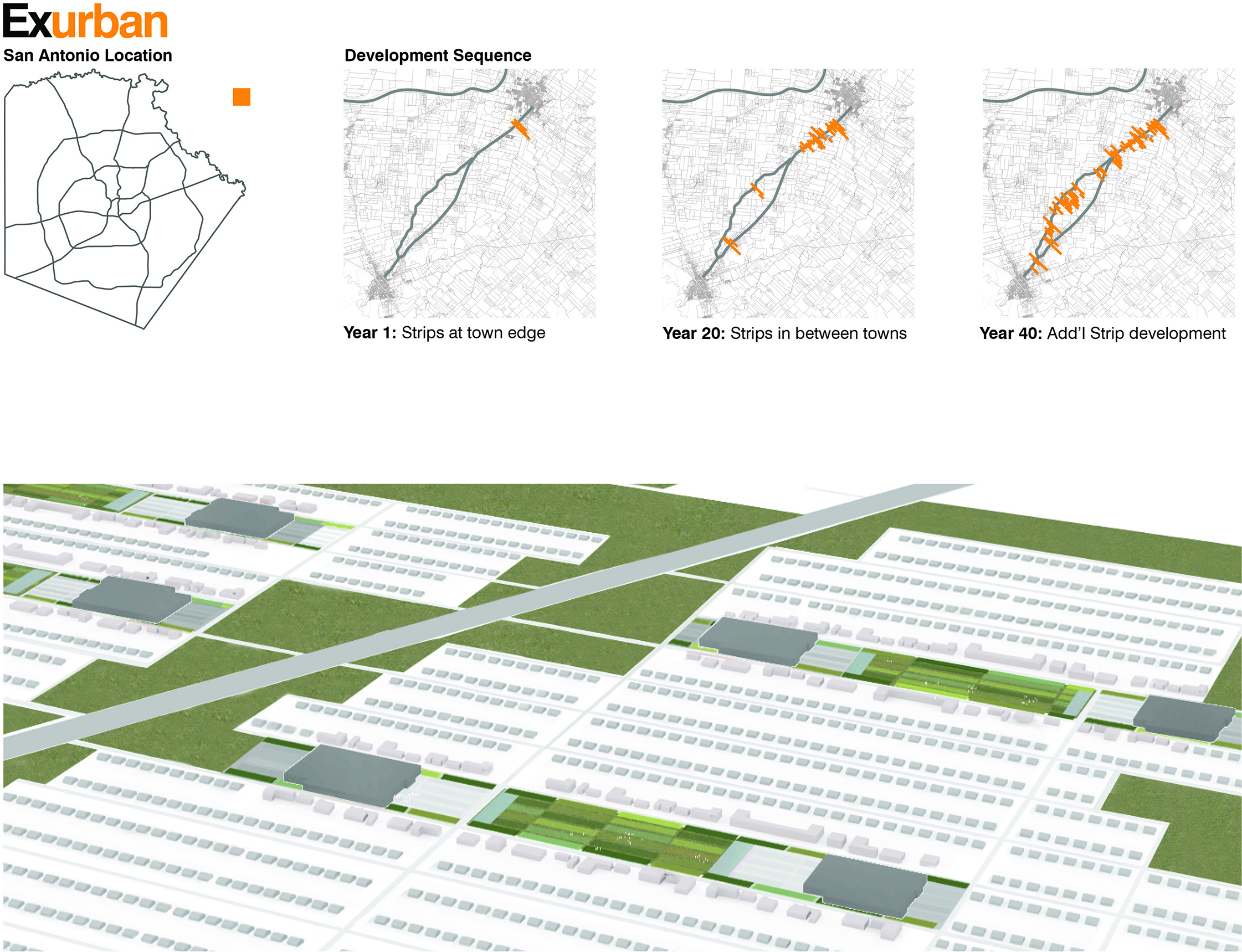

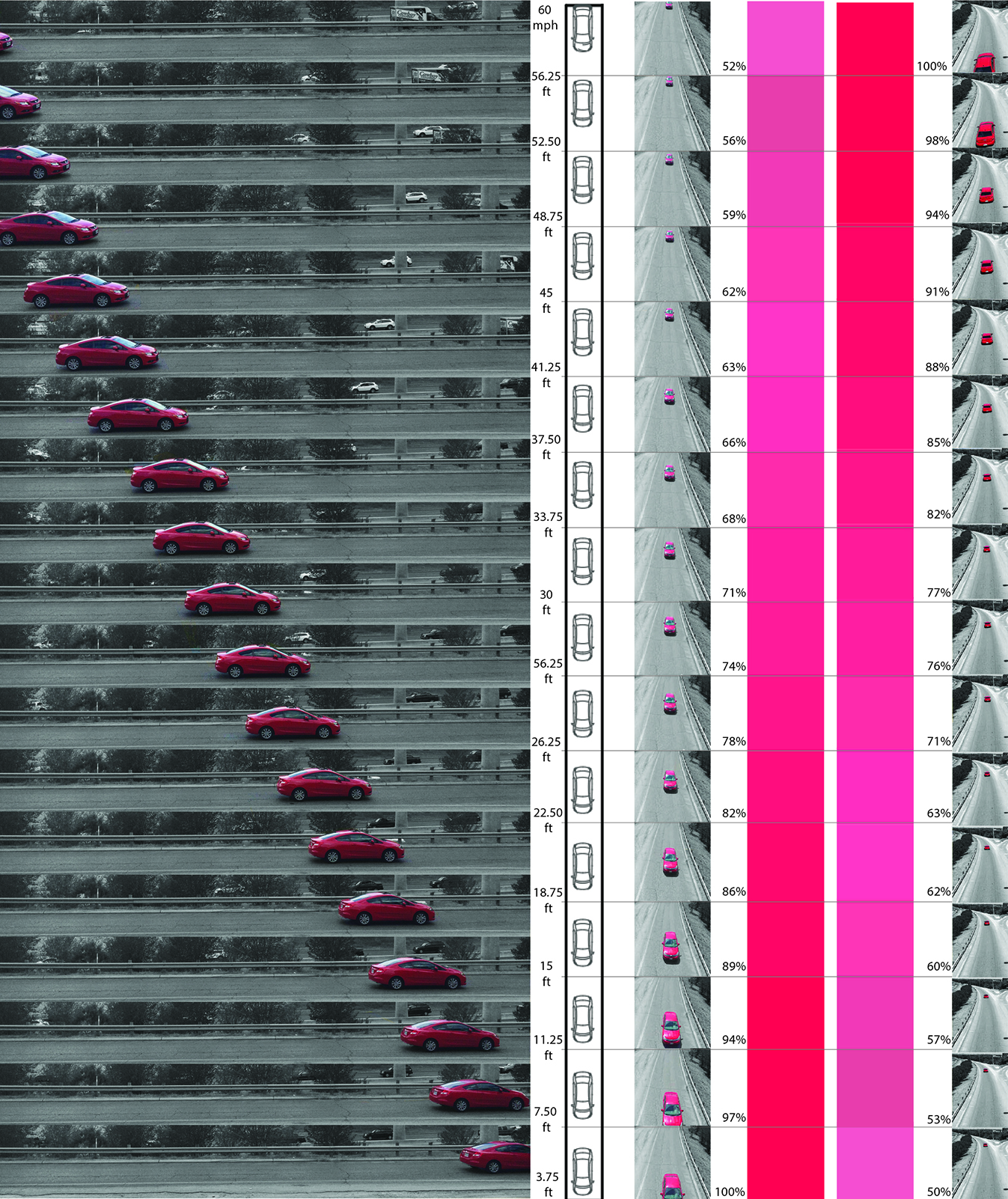

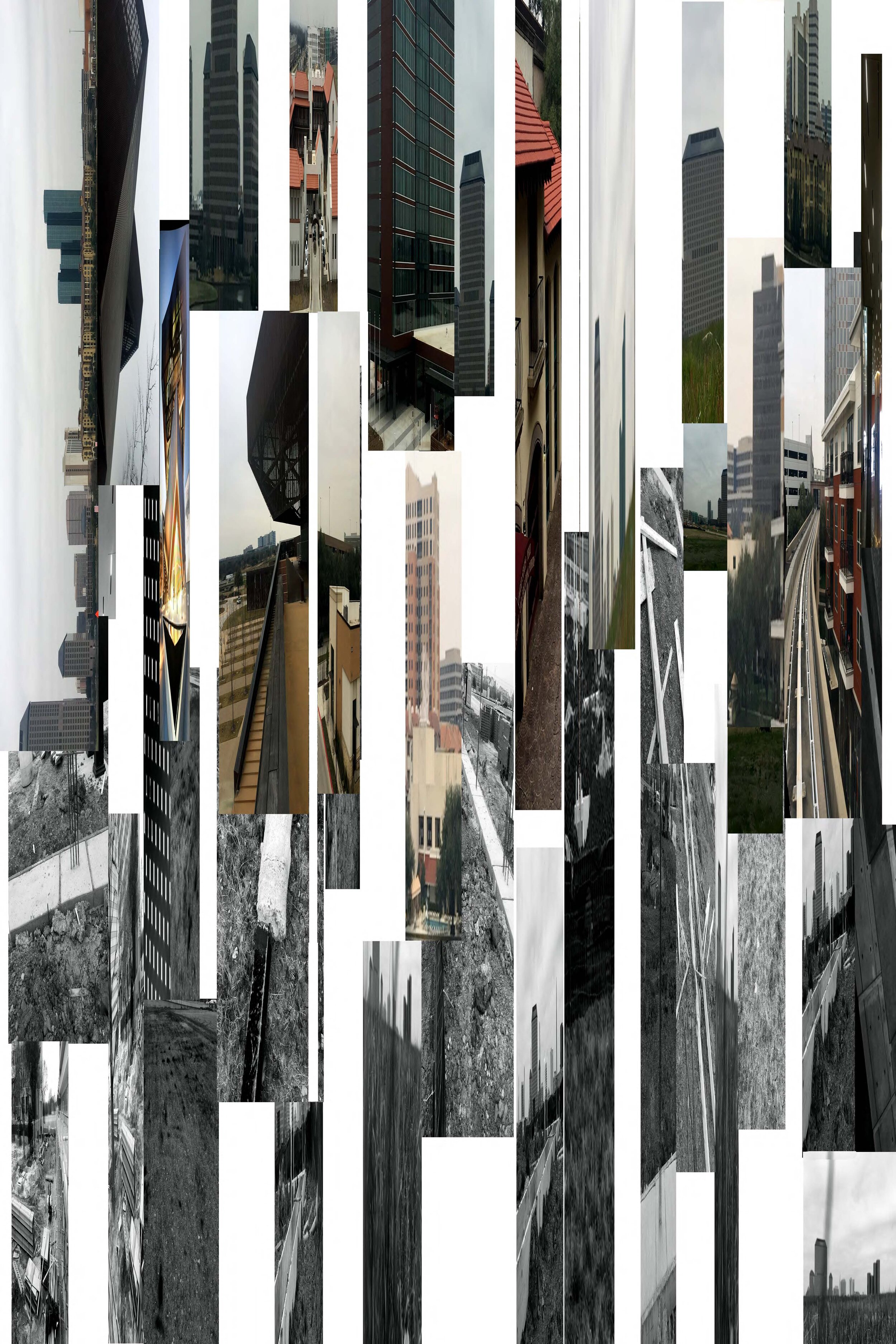

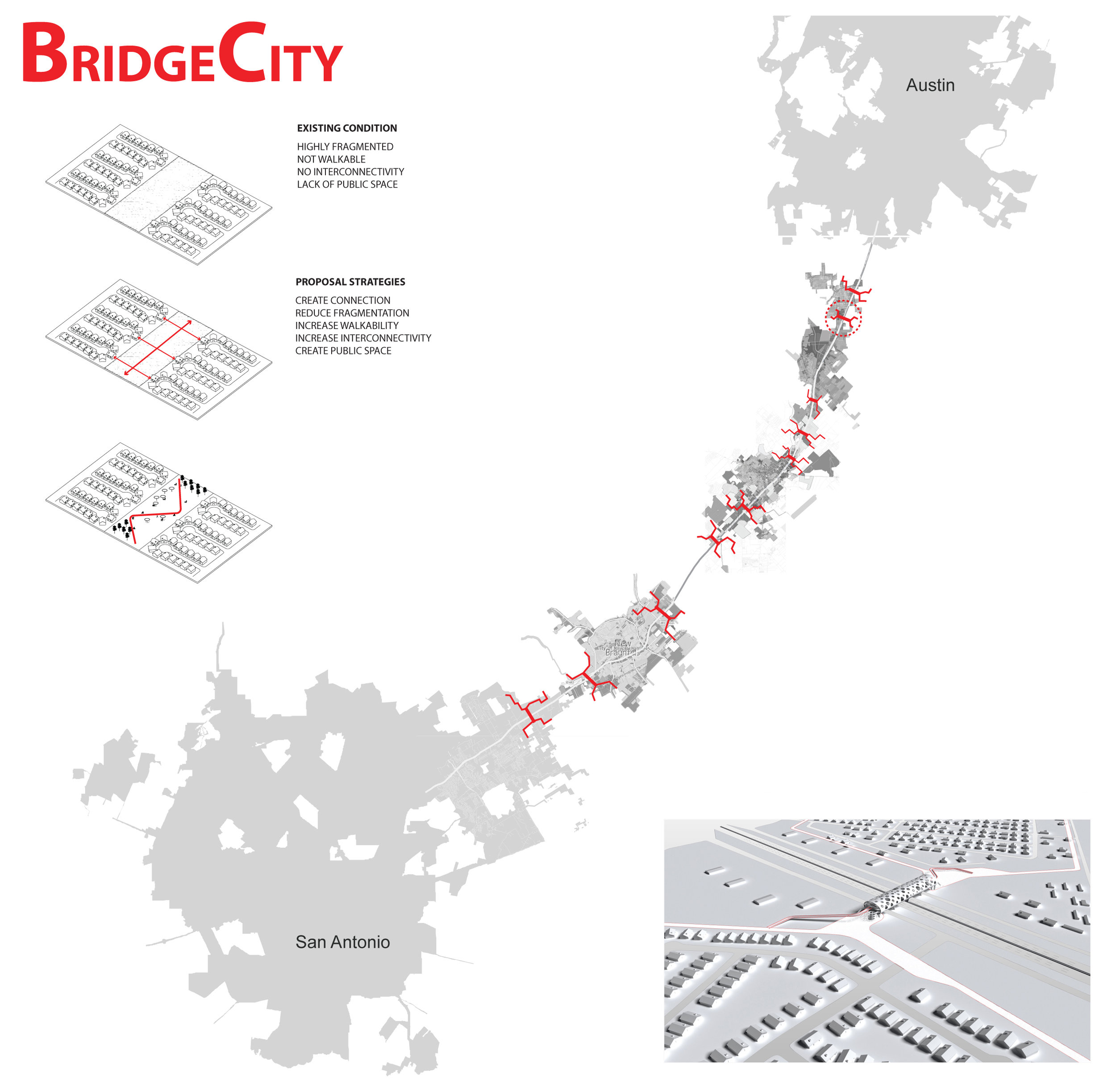

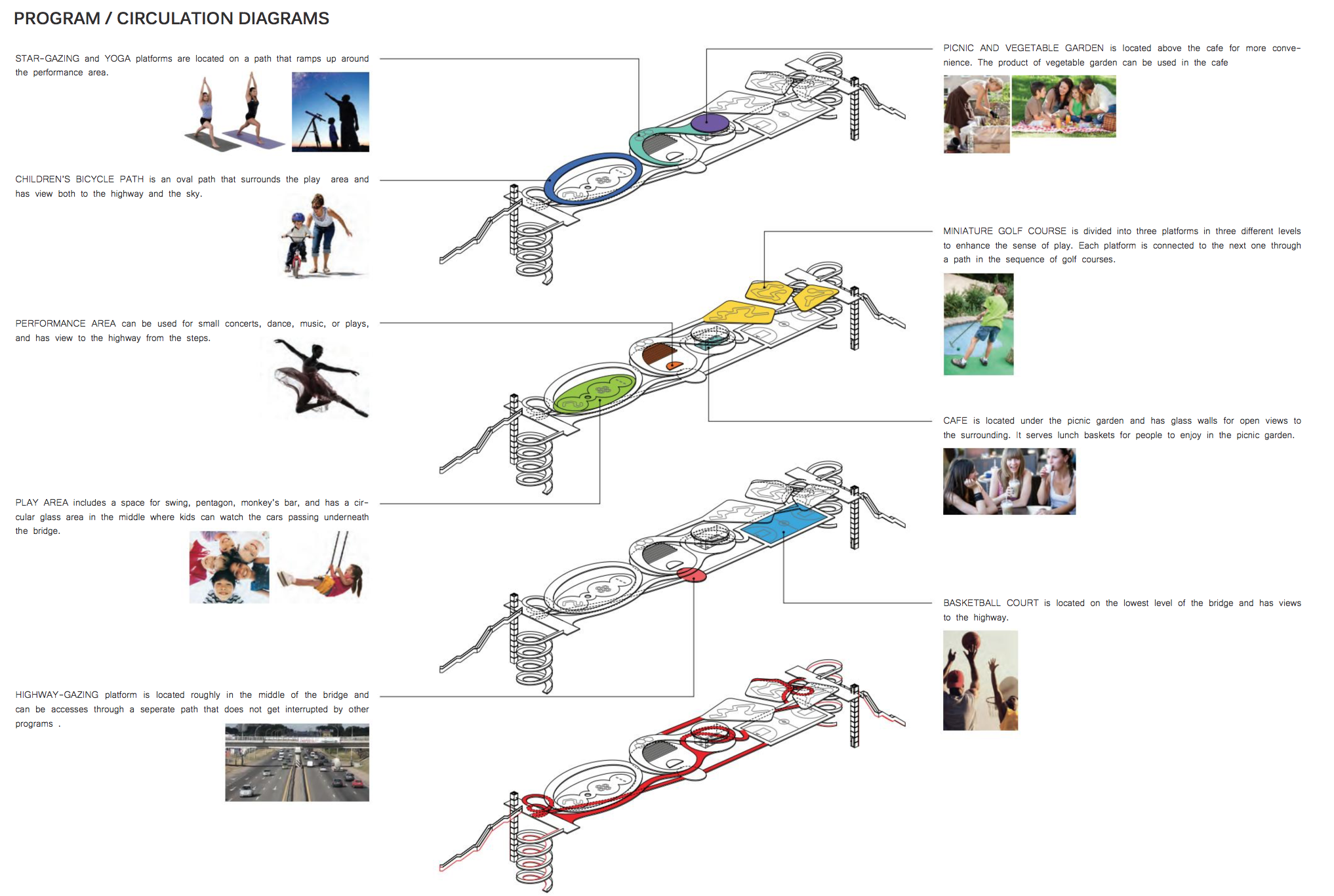

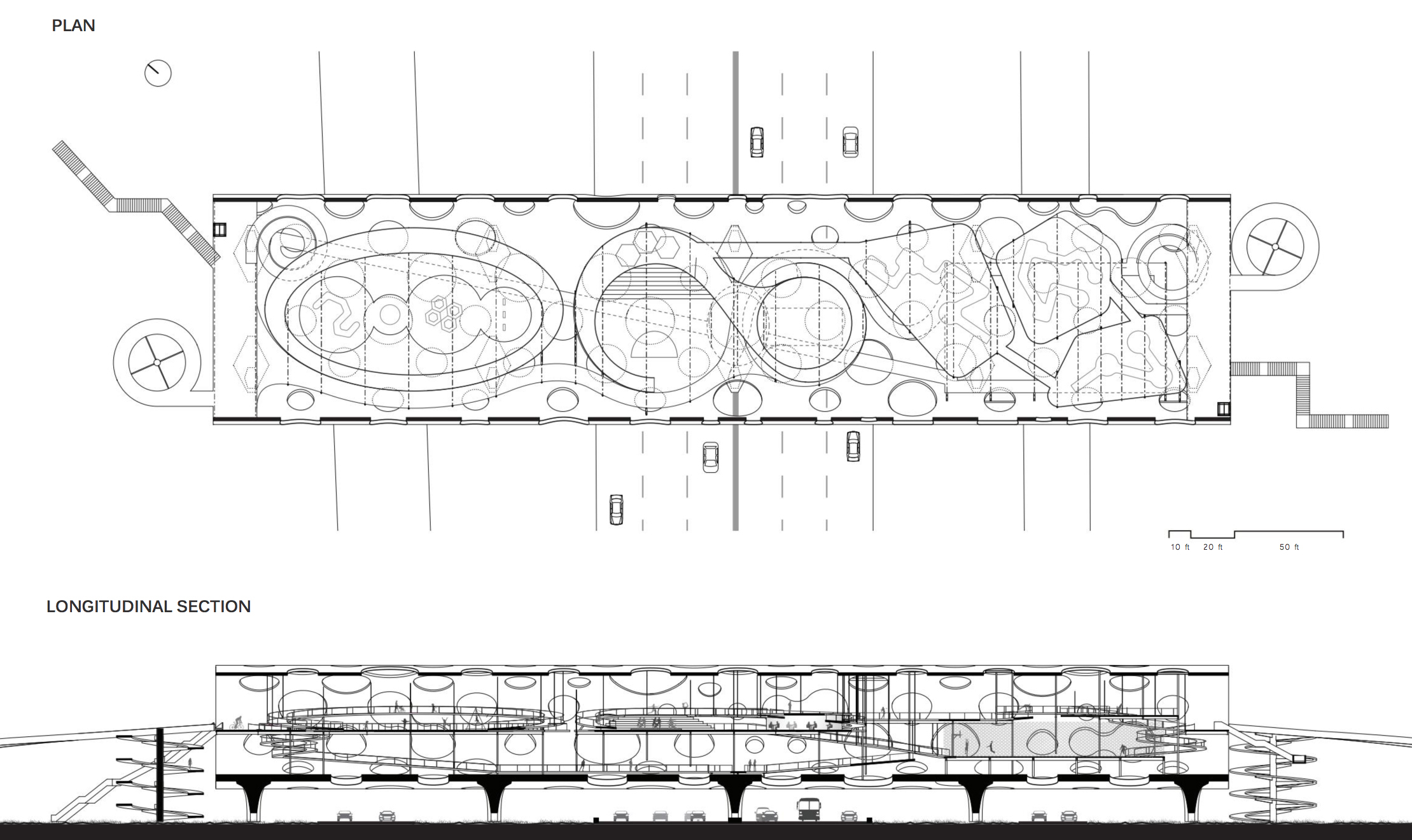

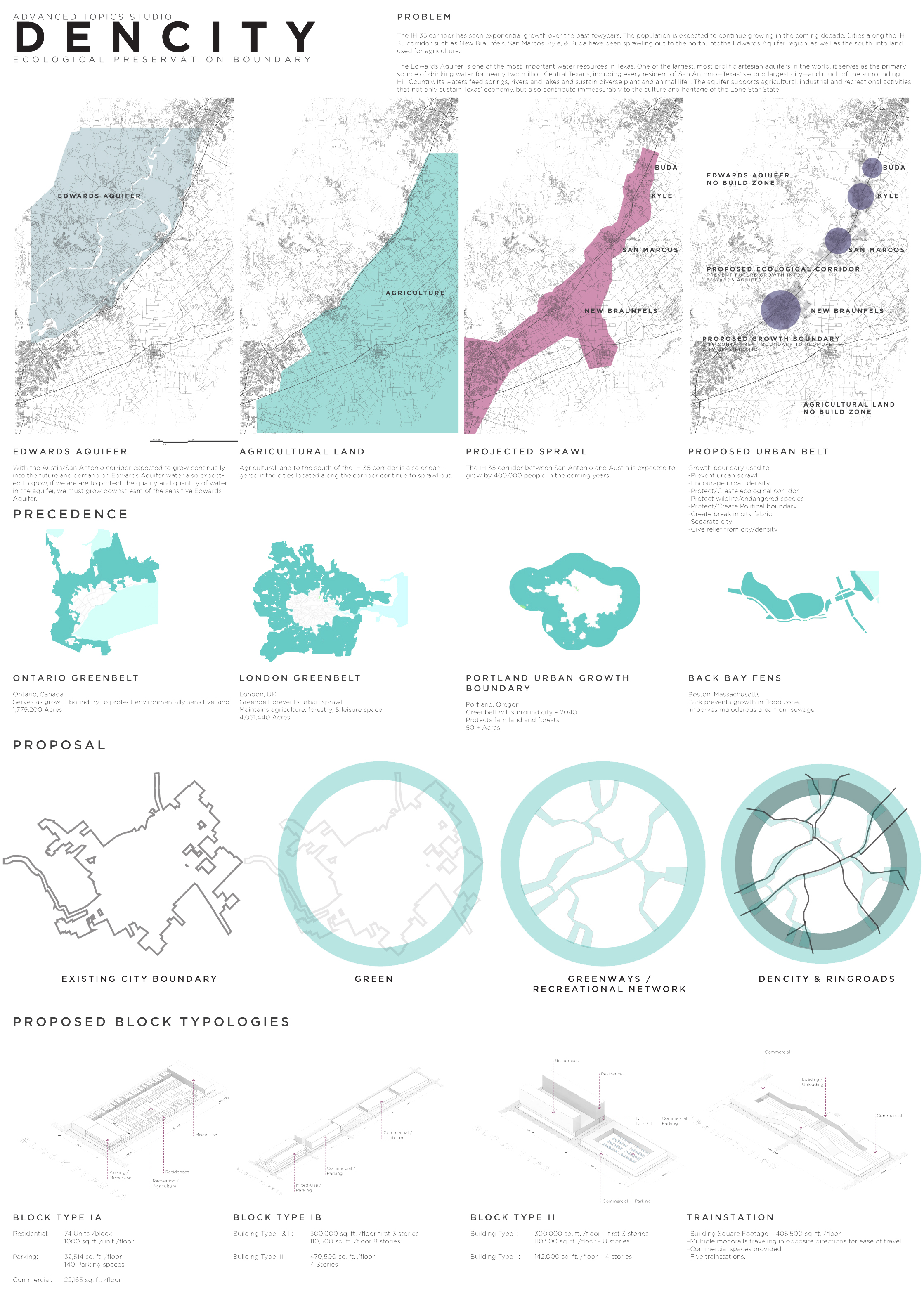

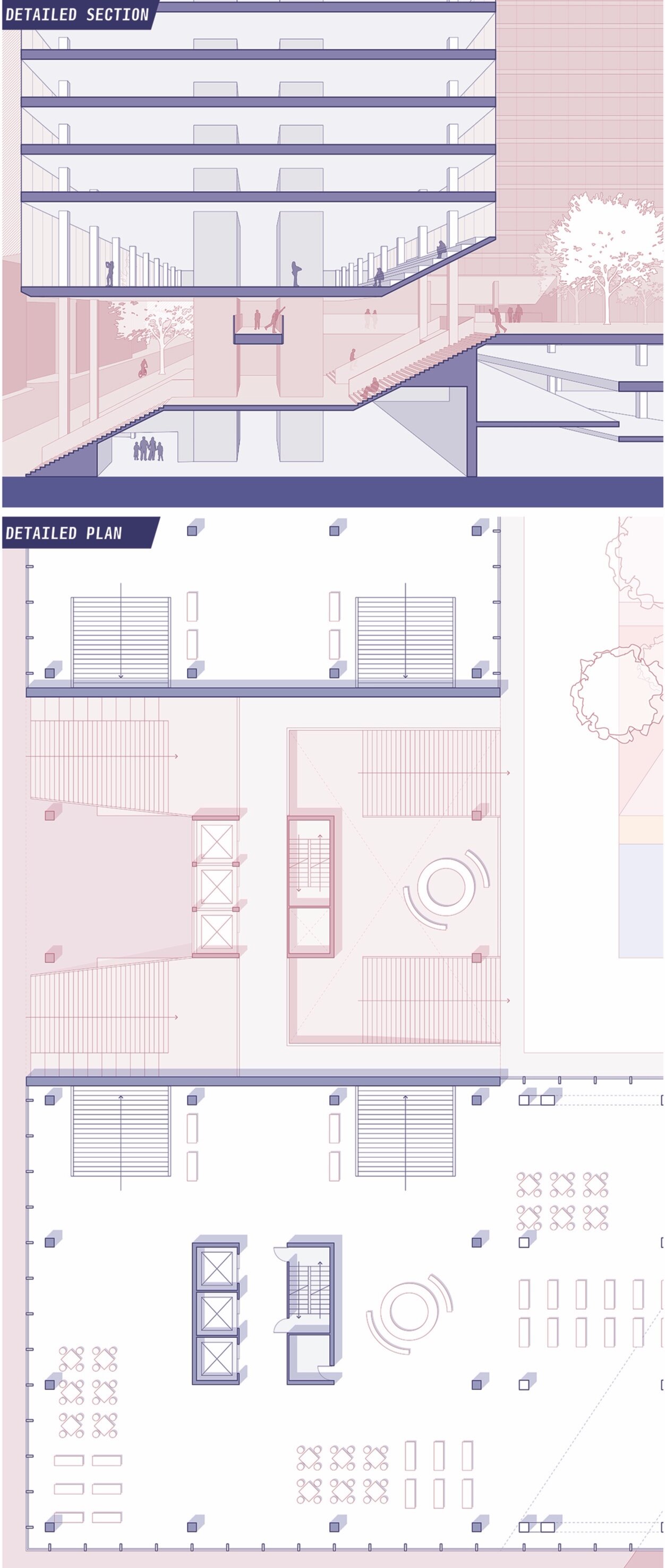

I-35 Unbound

University: UTSA

Type: Design Studio

Level: Advanced Graduate

Student Projects: Pegah Amini (Bridge City), Studio Research Book, Homero Montemayor and Tiffany Moreland (Den City)

Introduction

If there is to be a “new urbanism” it will not be based on the twin fantasies of order and omnipotence; it will be the staging of uncertainty; it will no longer be concerned with the arrangement of more or less permanent objects, but with the irrigation of territories with potential; it will no longer aim for stable configurations but for the creation of enabling fields… it will no longer be about meticulous definition, the imposition of limits, but about expanding notions, denying boundaries… it will no longer be obsessed with the city but with the manipulation of infrastructure for endless intensifications and diversifications, shortcuts and redistributions — the reinvention of psychological space.

Rem Koolhaas, “Whatever Happened to Urbanism” (1995) [1]

Twenty years after Koolhaas’ prescient words, here we are, still sorting through the implications and evaluating the possibilities. In the ensuing years, at least one unsettling paradox has emerged: while it is increasingly clear that we will never recapture the consolidated, dense urbanism of the pre-modern era; we have yet to establish any level of comfort with the expansive condition of the post-modern one. This semester we will address this paradox: first, undertaking an architectural research project that seeks to establish the existing components and logics of the contemporary city; and second, generating a series of strategic interventions in an attempt to establish new ones.

The site for our work is the I-35 Corridor, one of the longest and most active trade routes in the United States. Beginning in Laredo, Texas, the corridor stretches for over 1,500 Miles across six states before ending in Duluth, Minnesota. Along the way, it passes through some of the fastest growing cities in the U.S. including San Antonio, Austin, Dallas, Oklahoma City, Wichita, Kansas City, Des Moines, and Minneapolis. The economic and demographic importance of I-35 increased dramatically with the 1993 advent of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the trilateral trade agreement between the Mexico, the United States and Canada. At the international scale, the I-35 corridor is part of a larger system known as the Pan-American Highway. This route travels through 18 countries, winding its way from Argentina through Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Guyam, Suriname, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, and the United States before reaching Canada.

I-35 Unbound will focus on the landscape between San Antonio and Austin, utilizing the corridor as an armature to study urban growth within the Texas Triangle. This emerging mega-region has experienced significant economic growth over the past several decades—the result of increasing oil and gas extraction, continued immigration, and continued low housing prices. Much of the demographic expansion is taking place along I-35, home to three of the top ten fastest growing cities in the United States in Austin, San Marcos, San Antonio.

One fundamental goal of the studio is to illuminate the relationship between the visible and invisible logic of urban form along I-35. The studio begins with the assumption that the formal and spatial arrangements along I-35 bear very little resemblance to the traditional city and are therefore virtually impossible for planners, designers and policy-makers to discuss with any degree of confidence. In an attempt to remedy this conceptual shortcoming, the research aims to establish knowledge in four critical areas: the history of growth along I-35, the invisible networks that produce new growth along I-35, the infrastructures that facilitate new growth along I-35, and the urban morphologies that are the result of these patterns.

The Research

Urban Histories and Futures. The research begins with a timeline to establish the political, infrastructural, and economic history of the transnational route. The timeline starts with Incan efforts to establish a trade route in the 14th century and concludes with current attempts to establish an infrastructural supercorridor through Texas.

Urban networks. The next set of drawing represent urban networks along I-35. These networks, which drive the production of urban form and connect south Texas to the world beyond, come in many forms: trade, production, capital, routine, communication, and migration [5]. Kazys Varnelis, writing about Los Angeles in his book The Infrastructural City, emphasizes that in order to understand contemporary cities, we must understand the importance of the network: “Setting out to understand this city, and by extension all contemporary cities, we treat it in terms of networked ecologies, a series of codependent systems of environmental mitigation, land-use organization, communication and service delivery. In our analysis, these infrastructures form the basis of the contemporary city, but they are vastly different from the infrastructures of old. Rather than being executed in conformance with the outline of a plan, they are networked, hypercomplex systems produced by technology, laws, political pressures, with feedback mechanisms [6].”

Urban infrastructures. The research next documents material infrastructure, which is comprised of diverse physical networks like streets, electrical grids, airports--even large-scale buildings such as distribution centers. Consider the following prompt from Keller Easterling: “The building enclosures typically considered to be geometric formal objects have become infrastructural....No longer simply what is hidden or beneath another urban structure, many infrastructures are the urban formula, the very parameters of global urbanism...The seemingly innocuous layers of infrastructural space are filled with profound indicators about how the world really works [7].” The research will consider the power that these visible and architectural logics have on the production of urban space along I-35.

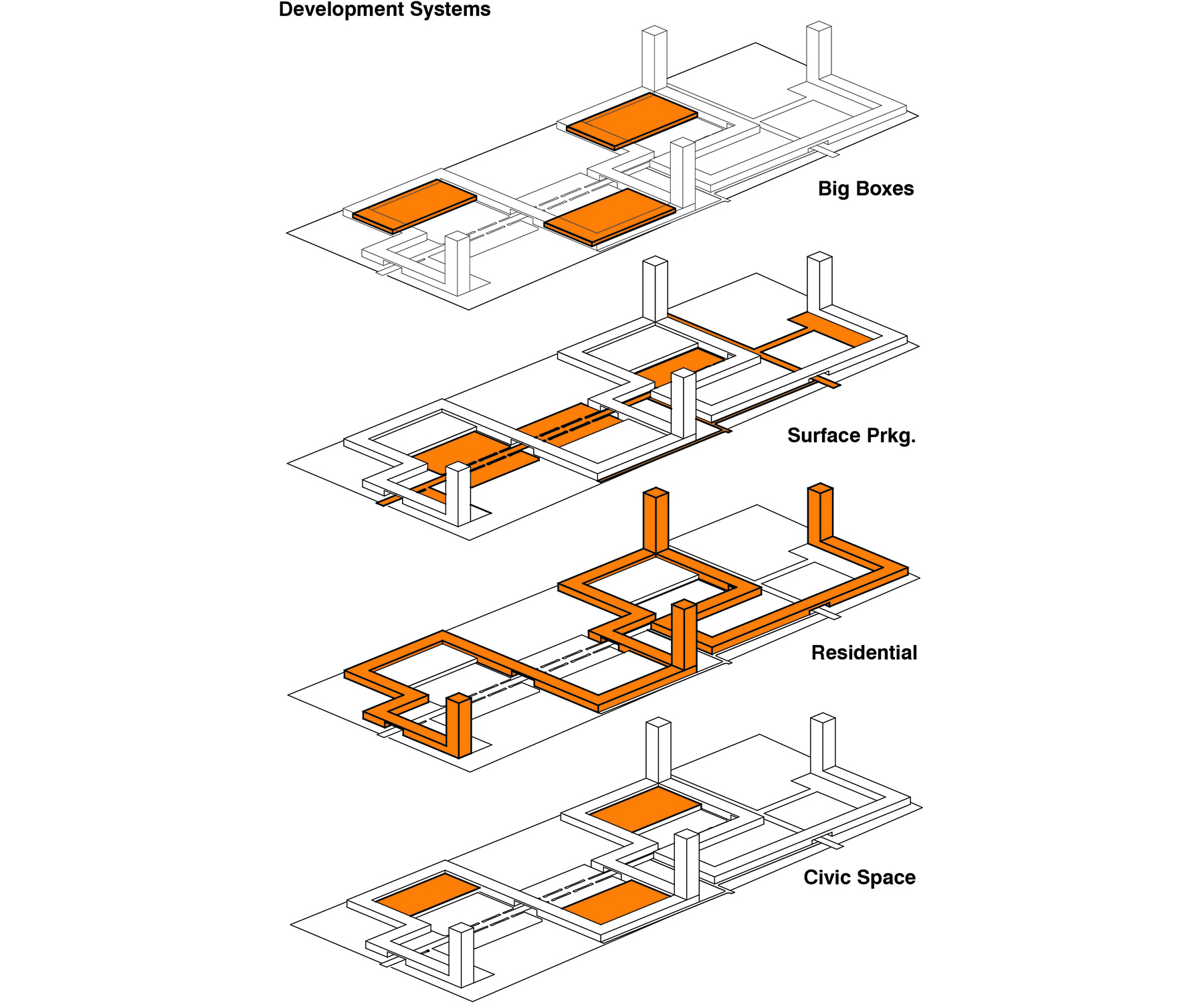

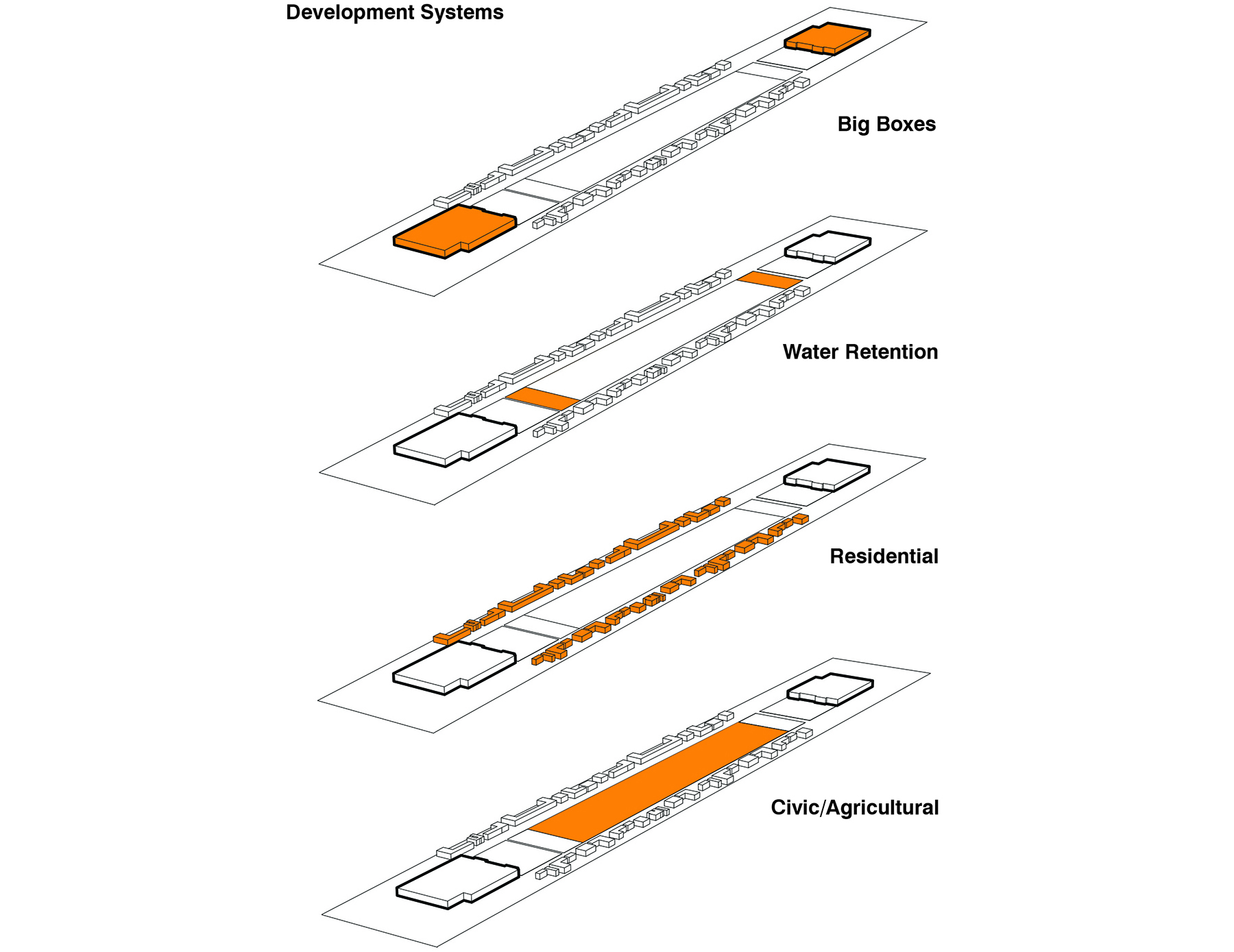

Urban Typologies. Finally, the studio considers form. An urban typology is a prototypical arrangement of space such as a big box development, a residential cul-de-sac, or a water park. The urban typologies that exist along I-35 bear little resemblance to those built in U.S. cities prior to WWII. The lack of familiarity makes it difficult for planners and policy-makers to project future scenarios with any degree of confidence. The research therefore seeks to establish a new taxonomy of urban development along I-35.

Finally, perhaps the best opportunities to improve landscapes like the I-35 Corridor lie in the repetition of forms and scenarios: after all, good design is just as easily multiplied as bad. By establishing a new understanding of history, networks, infrastructure and form, this studio intends to lay the groundwork for design interventions that are well informed and powerful enough to alter the trajectory of growth between San Antonio and Austin.

Principles for Design

Fortified by the research, the studio will develop a series of physical interventions based on the following principles:

Networks, not form. An urban network is a “...space of material interaction, exchange, meeting and encounter [8].” This semester we will resist the temptation to focus on form, instead considering the immense power that previously invisible logics have on the production of urban space along I-35.

Infrastructures, not buildings. Similarly, we will seek out the logic of material infrastructure in an attempt to leverage consider their impact on the production of urban space along I-35. As Stan Allen points out, infrastructure offers a pathway into a more democratic urbanism, suggesting possibilities rather than solutions [9].

Parts, not wholes. While we will focus on the systems, we will always focus on the parts. That is, we will engage the part, not the whole. We will begin with the assumption that one or a few incremental changes, strategically multiplied, might achieve a new, more coherent whole. This will be more promising strategy than trying to conceive a whole new whole, which is a not possible given the political circumstances that exist in south Texas and the United States today. So same ingredients, new recipe. One of our first tasks will be to discover just what ingredients we have at our disposal.

Hybrids, not singles. While the space in-between San Antonio and Austin appears to have enormous programmatic diversity, there is also very little overlap or exchange. It’s an architectural mono-culture. Where are the opportunities for programs to interact? To intersect? Can architectural hybrids emerge?

Proto-types, not one-offs. The I-35 Corridor was designed by capitalists (developers and bankers) and technocrats (transportation engineers, city bureaucrats). All of these groups like repetition. Therefore, we’ll seek prototypical situations that we can improve with design. One of the great opportunities to improve landscapes like the I-35 Corridor lies in the repetition of forms and scenarios: good design is just as easily multiplied as bad design. We’ll try to take advantage of this equivalency.

Scenarios, not utopias. Finally, this is an exercise in re-reading, re-calibrating, and re-proposing the existing components and systems that organize the space between San Antonio and Austin. The studio will proceed from the perspective that the underlying program of this space is acceptable, or at least, not amenable to change given our current political and economic structure. This assumption may be worthy of debate. Still, such discussions lie beyond the parameters of the studio. The exercise is therefore one that involves re-proposing the types and infrastructures of the I-35 Corridor. This will involve a series of physical operations: combining, hybridizing, re-organizing, multiplying, pushing, pulling, stacking, digging, removing, adding, re-ordering, prioritizing, privileging, registering, and marking.

Methodology

1: Observations: Types and Intersections. We will begin by closely observing the existing landscape between San Antonio and Austin: examining, representing, organizing. We will resist the temptation to evaluate or judge what we find. Instead we will draw, reduce, sort, curate, measure, categorize, chart, and count. In other words, we’ll do research. The two primary categories for our investigation will be types and infrastructures.

2. Scenarios: Architectural Fantasies. One of the primary impediments to urban change is our collective inability to see beyond existing circumstances. At this point in the semester we will temporarily suspend reality, generating possible, semi-possible, and perhaps a few impossible scenarios that re-configure the existing typologies and infrastructures along the I-35 Corridor. We’ll then evaluate the opportunities and constraints of each and select the most promising ones for development.

3: Interventions: Intersections and Hybrids. New scenarios in hand, we’ll propose a series of hybrid typologies that re-establish their relationship with existing and re-configured infrastructures. The goal will be to create more sympathetic, productive, or efficient arrangements of the pre-existing programs along I-35.

4: Multiples: Finally, we will attempt to project the logic of such arrangements across a larger territory, projecting their potential impact as far as possible. Would such incremental shifts impact the I-35 Corridor at a larger scale? Would they resonate in San Antonio? In Austin?

[1] Rem Koolhaas, “Whatever Happened to Urbanism”, in S,M,L,XL. (New York: Monacelli Press, 1995), 969-971.

[5] Schmid, Christian. “Networks, Borders, Differences: Towards a Theory of the Urban?”, Implosions/Explosions:Toward a Study of Planetary Urbanism, ed. Neil Brenner (Berlin: Jovis, 2014). 76.

[6] Kazys Varnelis, “Introduction: Networked Ecologies,” in The Infrastructural City: Networked Ecologies in Los Angeles, ed. Kazys Varnelis (Barcelona/New York: Actar, 2009). 15.

[7] Easterling, Keller, “Fresh Field,” in Bhatia, Neeraj et al, Coupling: Strategies for Infrastructural Opportunism. (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2011). 10-13.

[8] Schmid, Christian. “Networks, Borders, Differences: Towards a Theory of the Urban?”, Implosions/Explosions:Toward a Study of Planetary Urbanism, ed. Neil Brenner (Berlin: Jovis, 2014). 76.

[9] Stan Allen, “Landscape Infrastructures,” in Katrina Stoll & Scott Lloyd, Infrasructure as Architecture Designing Composite Networks. (Berlin: Jovis, 2010).

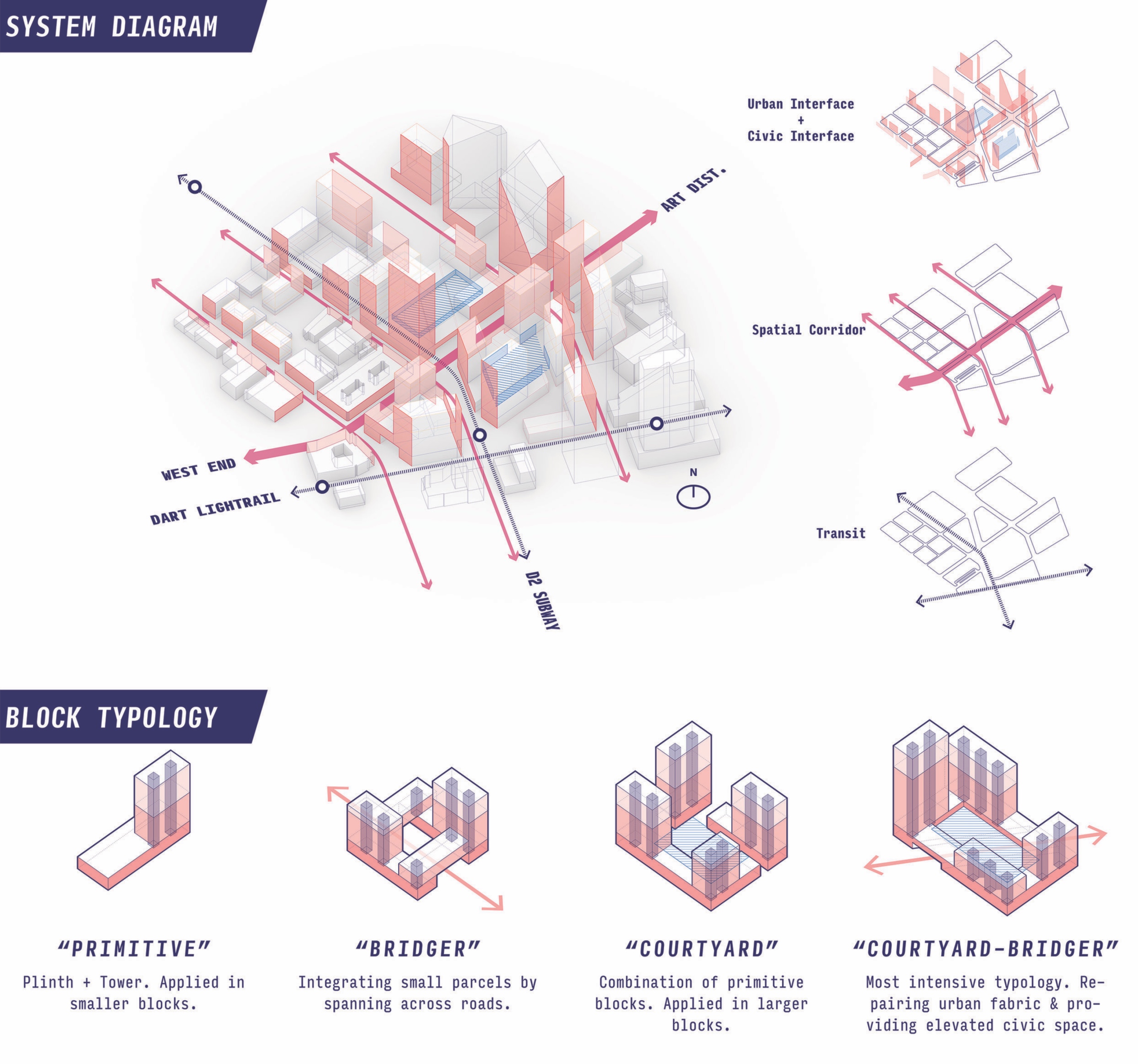

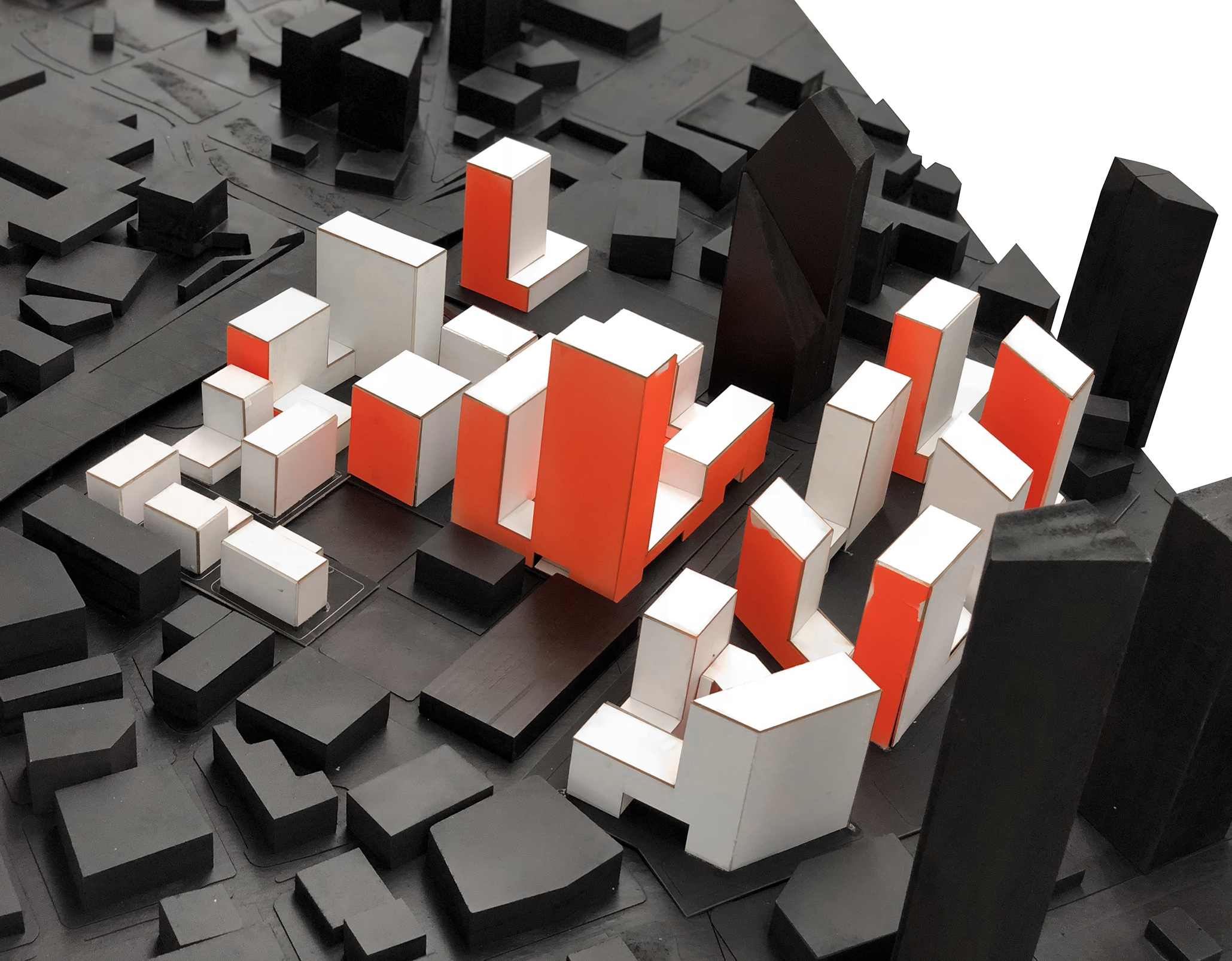

New Growth Strategies for the Polycentric City [Projects]

University: Washington University

Type: Urban Design Studio

Level: First Year Master of Urban Design

Student Designers: Weitu Zeng, Ayman Rouhani, Christine Doherty

Studio Introduction

Growth, growth, and more growth. This semester the studio will travel to the fourth largest metropolitan area in the United States, the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, to investigate rapid urban growth within the North American context [i]. Founded in 1841, Dallas began to emerge as a major financial and freight center with the discovery of oil in the 1930s. Today, Dallas is home to twenty-two Fortune 500 companies, which is five more than London and just two less than New York [ii]. Each month, Dallas-Fort Worth adds 12,000 people to its population, making it the second-fastest growing metropolitan area in the U.S., trailing only Houston [iii]. Current estimates indicate that the metropolitan area will absorb 3.8 million more residents by the year 2040, a 54% increase that will swell the overall population from 7.1 to 10.9 million residents [iv]. Where will all of these people live, shop, and work? How will they move through the city? And most importantly, what will be the quality and character of the urban landscapes that they inhabit?

These growth trends extend to the regional scale, where Dallas Fort-Worth comprises one leg of the Texas Triangle, a megaregion that includes five of the ten fastest growing large cities in the U.S. (Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, Houston, and Austin) [v]. In 2009 the Texas Triangle covered 60,000 square miles, was home to 15 million residents, and was busy planning for another 10 million people by mid-century [vi]. By 2040, Texas will be home to two of nation’s five megacities, defined as areas of continuous urban development of over 10 million people [vii]. The demographic and economic foundation for the megaregion’s rapid ascent is built on steady immigration from Mexico and the U.S., business-friendly regulations, consistently low housing prices, and massive oil and natural gas reserves. Globally, Dallas Fort-Worth is also positioned along the I-35 Corridor, one of the longest and most active trade routes in the continental U.S., and a primary freight corridor to Mexico. The economic and demographic importance of I-35 increased dramatically with the 1993 advent of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the trilateral trade agreement between the Mexico, U.S., and Canada.

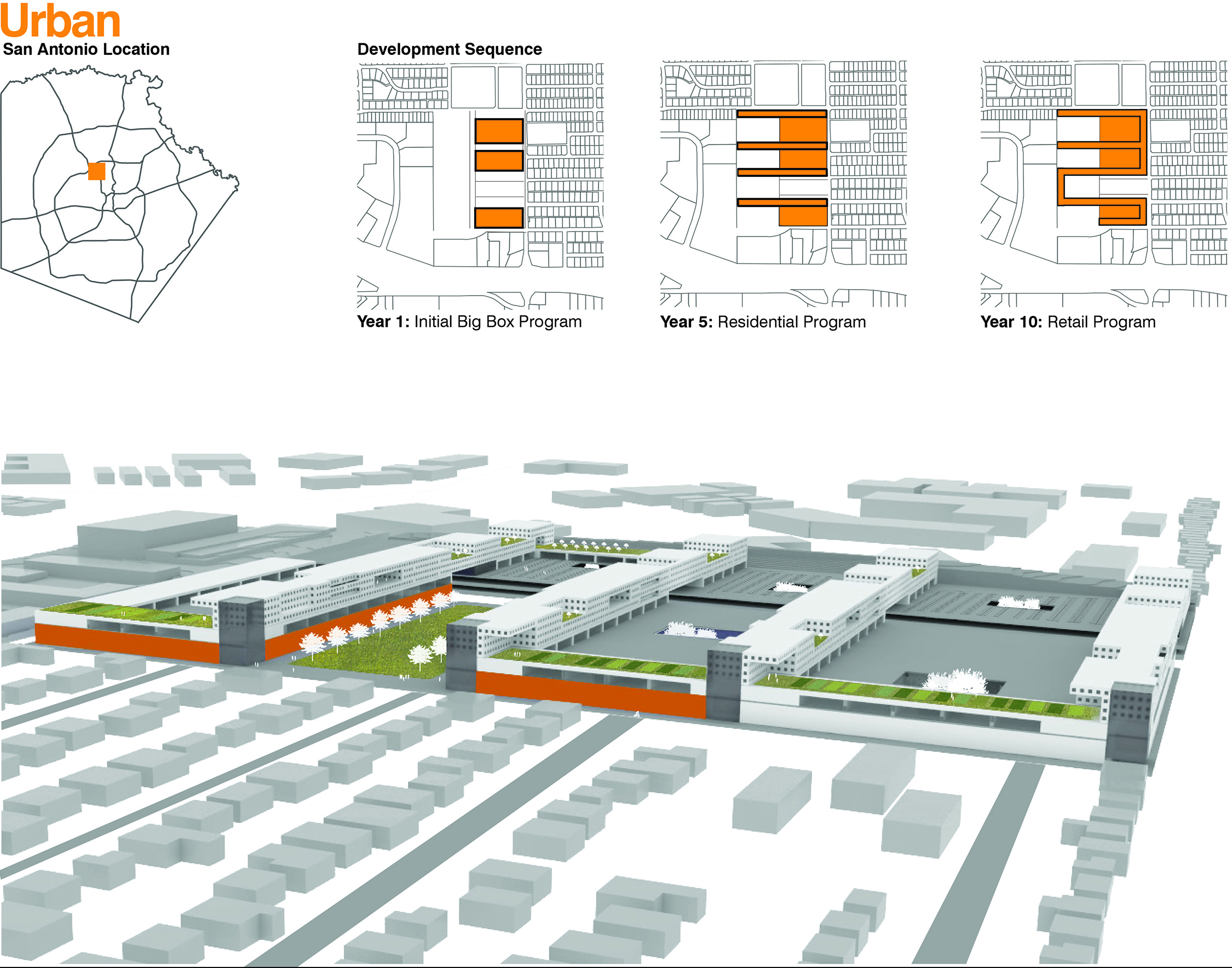

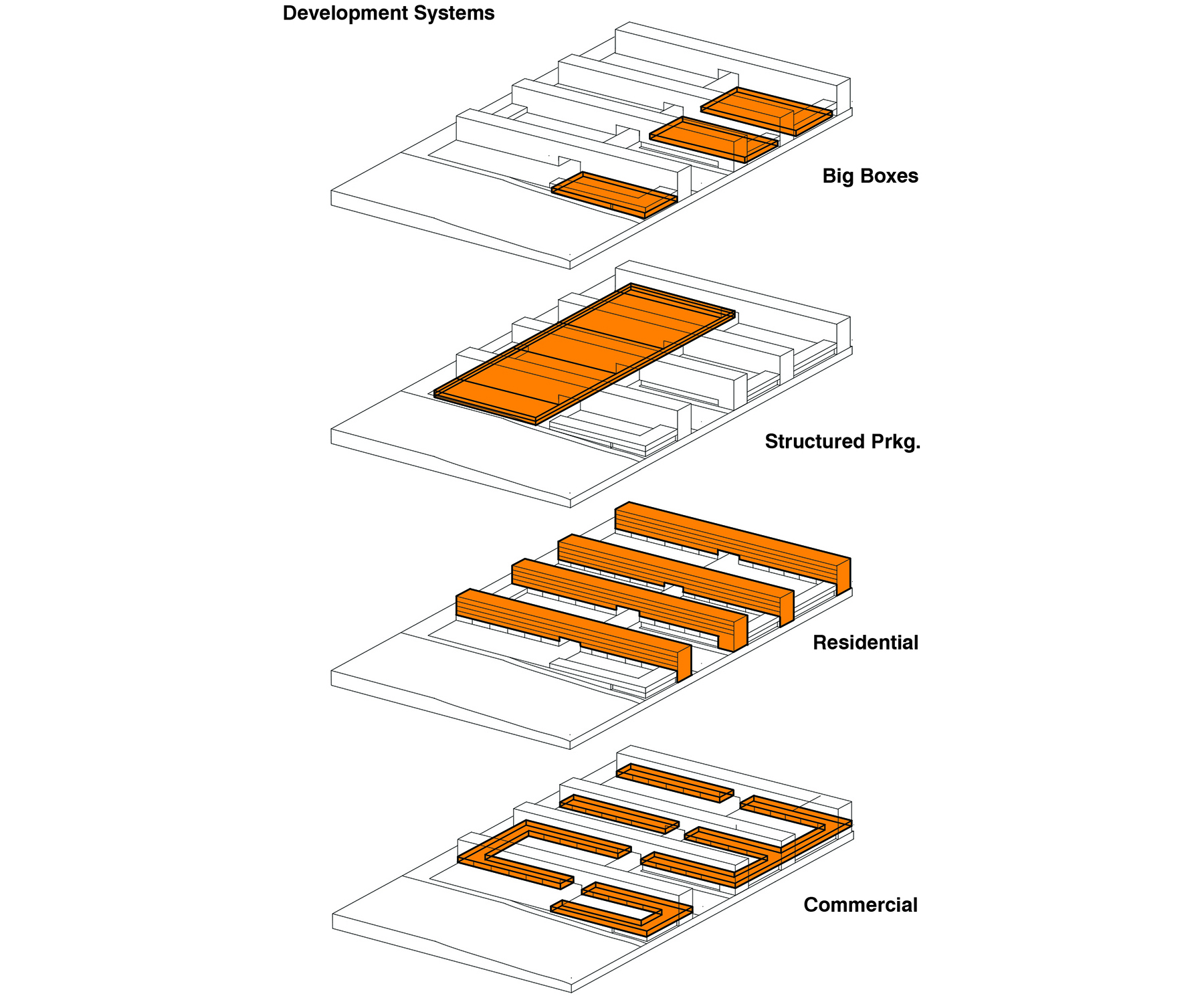

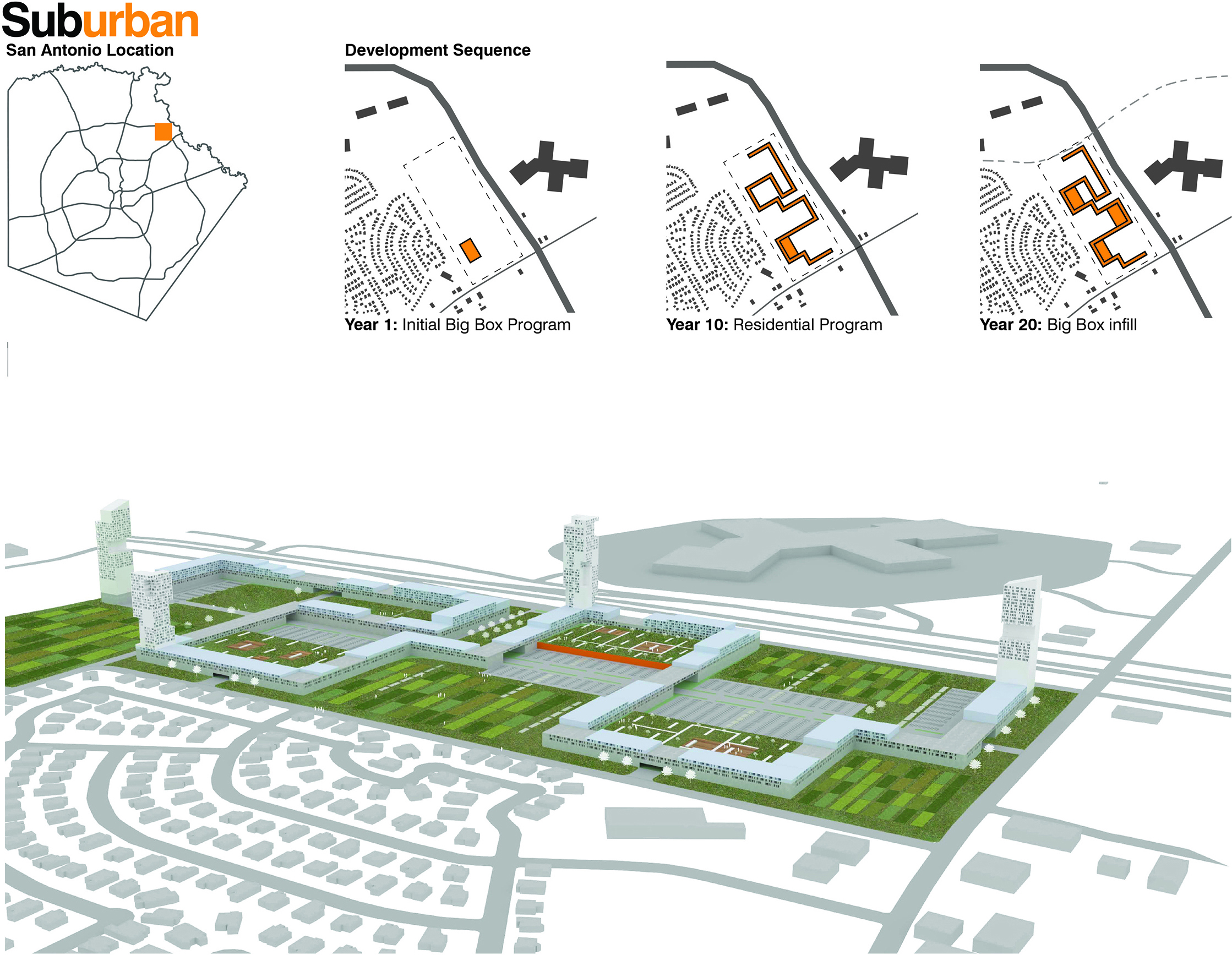

If current growth projections for the metropolitan areahold, the vast majority of urban development will take place at its northern periphery, well beyond the limits of existing historic cores [viii]. This means growth will cluster in adjacent cities like Frisco and McKinney; in Edge City developments like Richardson and Las Colinas; in and around aging regional shopping malls like Valley View Mall and Redbird Mall; and of course, within the rapidly gentrifying downtown cores of Dallas and Fort Worth. The intensely polycentric nature of this growth challenges “back-to-the city” redevelopment strategies that would prioritize the revitalization of historic cores and central business districts to the exclusion of peripheral areas. This studio argues that in order for Dallas-Fort Worth to successfully absorb the projected residential and economic growth, it must develop new planning scenarios that emphasize two fundamental realities: first, that the metropolitan area is a rapidly expanding, decentralizing landscape that will continue to resist geographic containment; and second, that this scenario will require the development of multiple, distinct urban nodes.

Moving from density to intensity. This semester, the studio will develop mechanisms to advance the spatial quality of development in these nodes. For years, designers and planners have proposed ways to measure the quality of urban space. Urbanist Jan Gehl offers the term “lively city” to describe an urban realm that appeals to a diversity of users and supports robust social interaction [ix]. Architects Allison and Peter Smithson similarly describe a “charged void,” in which the physical configuration of a space positively supports the activities of its users [x]. Policy-makers and planners often seek to quantify such phenomenon, most often proposing the concept of urban density, which uses established metrics such as population/square mile or units/acre to account for the people or program in a given space. The belief that higher density will generate spatial quality, of course, rests on the assumption that with more people and program, levels of interaction and therefore spatial quality will increase.

This studio will look beyond purely quantitative measures like density, considering as an alternative the concept of urban intensity. Researchers ChengHe Guan and Peter Rowedefine urban intensity as a measure of compactness, diversity, density, and connectivity [xi]. Others conceive it as the concentration of commercial and service activities adjacent to city streets [xii]. Such efforts to assess the quality of urban environments are promising because they look beyond the quantification of people and program, adding considerations of space and interaction.

This semester, the studio will generate urban design interventions in multiple development nodes throughout the metropolitan area, confronting two critical questions: First, what constitutes urban intensity within the rapidly expanding, decentralizing landscape of the Texas Triangle? Second, what mechanisms can designers rely on to generate urban intensity within an increasingly dispersed, polycentric framework?

The dissolving distinctions between urban, suburban, and exurban form. As the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex expands and decentralizes, traditional distinctions between urban, suburban, and exurban landscapes continue to dissolve, making established programs and forms increasingly obsolete [xiii]. As a response to this increasingly fluid situation, the studio will generate new spatial and programmatic arrangements for emerging development nodes throughout the metropolitan area. In each of these nodes, designers will generate redevelopment scenarios that introduce spatial compactness, programmatic diversity, residential density, and connectivity to existing fabric [xiv]. This will require designers to confront a series of complex questions: What spatial mechanisms are available to intensify experience? How will emerging urban nodes be programmed? How can designers intensify connectedness within nodes? How can designers intensify connectedness with adjacent urban fabric? With the rest of the metropolitan area? What will be the formal and spatial arrangements within each node? How can new public private partnerships better facilitate growth? The studio will act on the assumption that currently, urban designers and policy-makers lack clear and tested answers to these questions.

Re-concentrating growth within an expanding polycentric metropolitan structure. Planners in Dallas and Fort Worth expect that the majority of residential growth will take place at what is now the northern fringes of the Metroplex, extending a historical pattern of residential growth that continues to redirect investment away from the historic urban cores [xv]. Such trends began in the late nineteenth century with the advent of the electric streetcar, then accelerated throughout the twentieth century with the widespread adoption of the automobile, construction of the federal interstate system, and advent of metropolitan ring-roads.

Within the last forty years, an equally significant trend has challenged the primacy of Dallas and Fort Worth’s urban cores: namely, the polycentric development of employment centers throughout the metropolitan area. In order to understand this phenomenon, one need simply compare current employment densities, which remain highly concentrated in the historic downtowns and early Edge Cities, with projected employment growth, which will re-distribute jobs into several dozen pockets throughout the larger Metroplex.

These growth scenarios, which represent the norm in growing U.S. cities, make clear that a polycentric growth model will be required to absorb projected residential and employment growth. The studio will therefore examine multiple scenarios and locations for growth, generating new urban typologies capable of intensifying civic space within the expanding and dispersing metropolitan area.

Studio sites. The sites for this semester’s work represent a cross-section of the contemporary metropolitan landscape in Dallas-Fort Worth, including sites in the historic downtown, defined by the city’s initial nineteenth century infrastructure; in the inner-ring suburbs, which emerged with the advent of mid-century ring-roads; and at the metropolitan periphery, which arose as independent, or Edge Cities. Designers will generate redevelopment scenarios for each of the following critical urban typologies, envisioning powerful programmatic, regulatory, and spatial futures.

1 | Downtown Infill | Dallas and Fort Worth

Downtown Infill projects will seek to leverage the infrastructural and spatial logic of downtown Dallas and Fort Worth, intensifying spatial compactness, programmatic diversity, density, and connectivity to the historic core of the city.

2 | Suburban Retrofit | Carrolltown and Redbird Mall

Suburban Retrofit projects will reformulate the programmatic and spatial logic of an inner ring railroad suburb and a midcentury shopping mall, reusing infrastructure wherever possible, and reinventing wherever necessary.

3 | Edge City Redevelopment| Las Colinas and Cityline

Edge City Redevelopmentprojects will intensify the civic realm of two fast growing employment centers which are commercially successful, yet lack a well-considered civic realm.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

This studio will provide students with an opportunity to

+ investigate contemporary urban design issues within the context of a fast-growing North American city

+ generate strategies to intensify the civic realm within dispersed, polycentric growth patterns

+ acquire mapping techniques capable of analyzing urban context with precision and breadth

+ use drawing to generate clear and formally powerful urban design proposals

+ practice designing across multiple scales from the site to the megaregion

+ consider the design of civic space as it relates to policy, culture, economics, and real estate dynamics

+ leverage the synergies that exist at the intersection of infrastructure, program, and urban form

+ develop a systems-based approach to urban design

+ develop a performance-based approach to urban design

+ gain experience working in professional collaborations

[i] United States Office of Management and Budget, 2010.

[ii] Dallas Chamber of Commerce, “States with the Most Fortune 500 Companies.” www.cdn.dallaschamber.org/wpcontent/uploads/2016/03/The-Business-Community-Fortune-10001.pdf. (accessed December 17, 2017).

[iii] United States Census Bureau, 2016.

[iv] Dallas Business Journal, 2016.

[v] United States Census Bureau, “The 15 Cities With the Largest Numeric Increase Between July 1, 2014, and July 1, 2015, With Populations of 50,000 or more on July 1, 2014.” www.census.gov/newsroom/pressreleases/2016/cb16-81.html. (accessed December 21, 2016).

[vi] Kent Butler et al., “Reinventing the Texas Triangle: Solutions for Growing Challenges.” University of Texas at Austin: Center for Sustainable Development (2009): 14. www.cqgrd.gatech.edu/sites/files/cqgrd/files/texas_triangle_2009.pdf. (accessed January 15, 2015).

[vii] Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox, “The World's Fastest-Growing Megacities.” Forbes.com. www.forbes.com/sites/joelkotkin/2013/04/08/the-worlds-fastest-growing-megacities

[viii] Dallas Regional Chamber, 2017

[ix] Gehl, Jan, Cities for People. Washington, Covelo, London: Island Press, 2010. p.63.

[x] Allison Smithson, Peter Smithson, The charged void : urbanism, New York: Monacelli Press, 2005.

[xi] ChengHe Guan, Peter G. Rowe, The concept of urban intensity and China's townization policy: Casesfrom Zhejiang Province. Cities, 06/2016, Volume 55.

[xii] Andres Sevtsuk, Onur Ekmekci, Farre Nixon, Reza Amindarbari, Capturing urban intensity. Working paper, City Form Lab, unpublished.

[xiii] For more on this topic, see assigned reading by DeJong, Judith, New SubUrbanisms. (London: Routledge, 2013).

[xiv] See ChengHe Guan, Peter G. Rowe, The concept of urban intensity and China's townization policy: Casesfrom Zhejiang Province. Cities, 06/2016, Volume 55.

[xv] Dallas Regional Chamber, 2017.

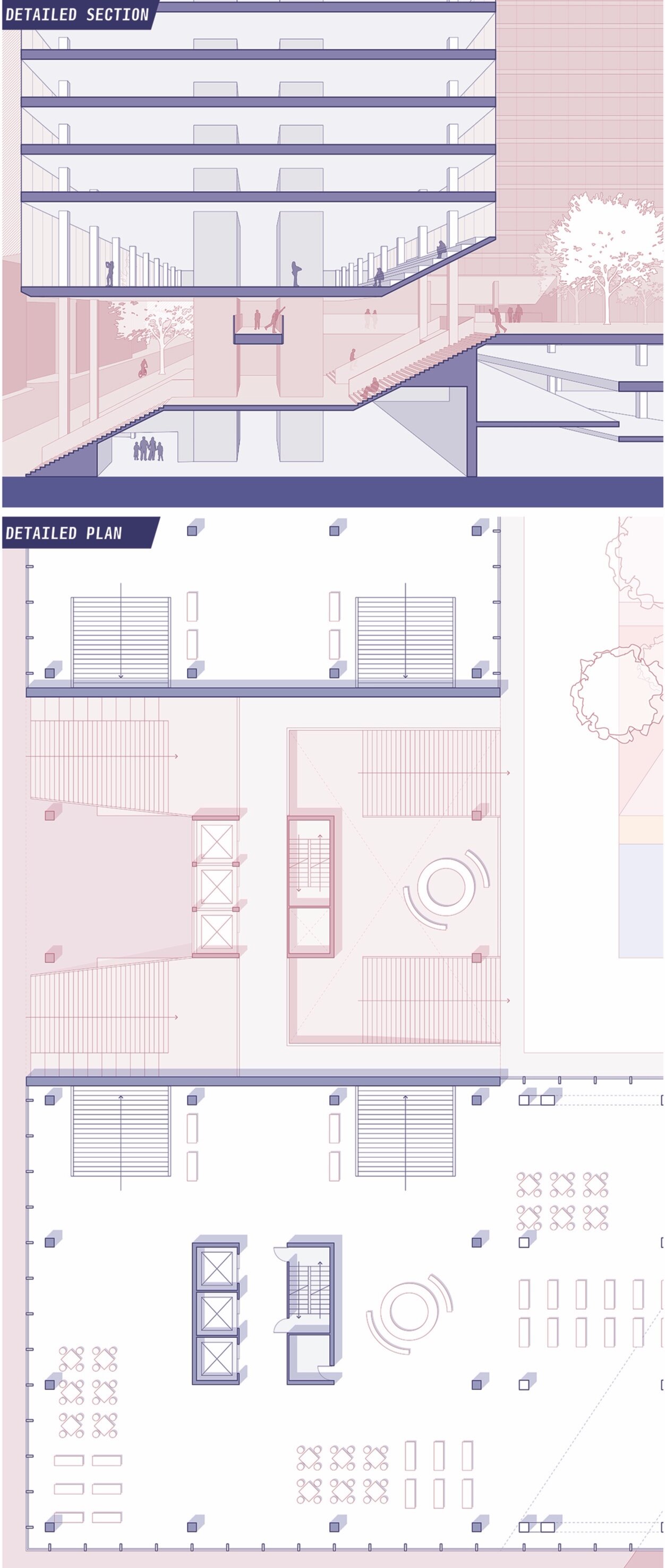

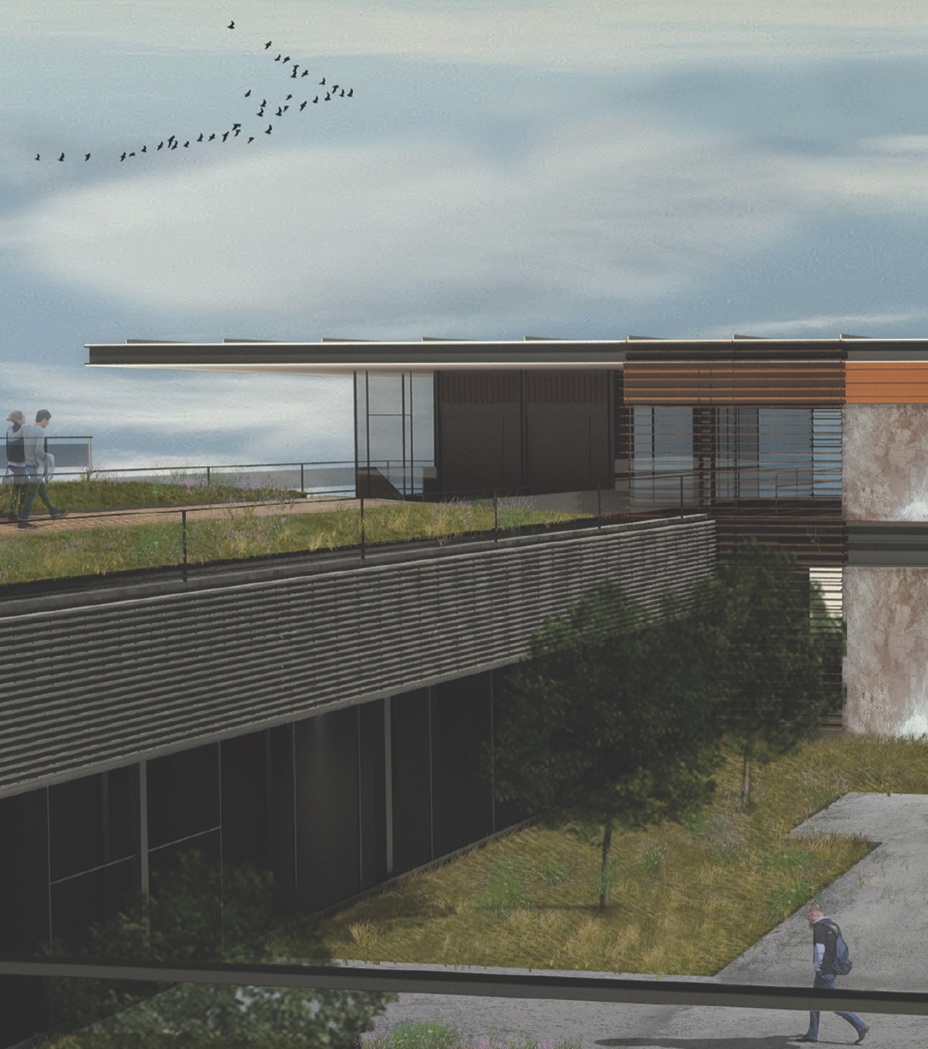

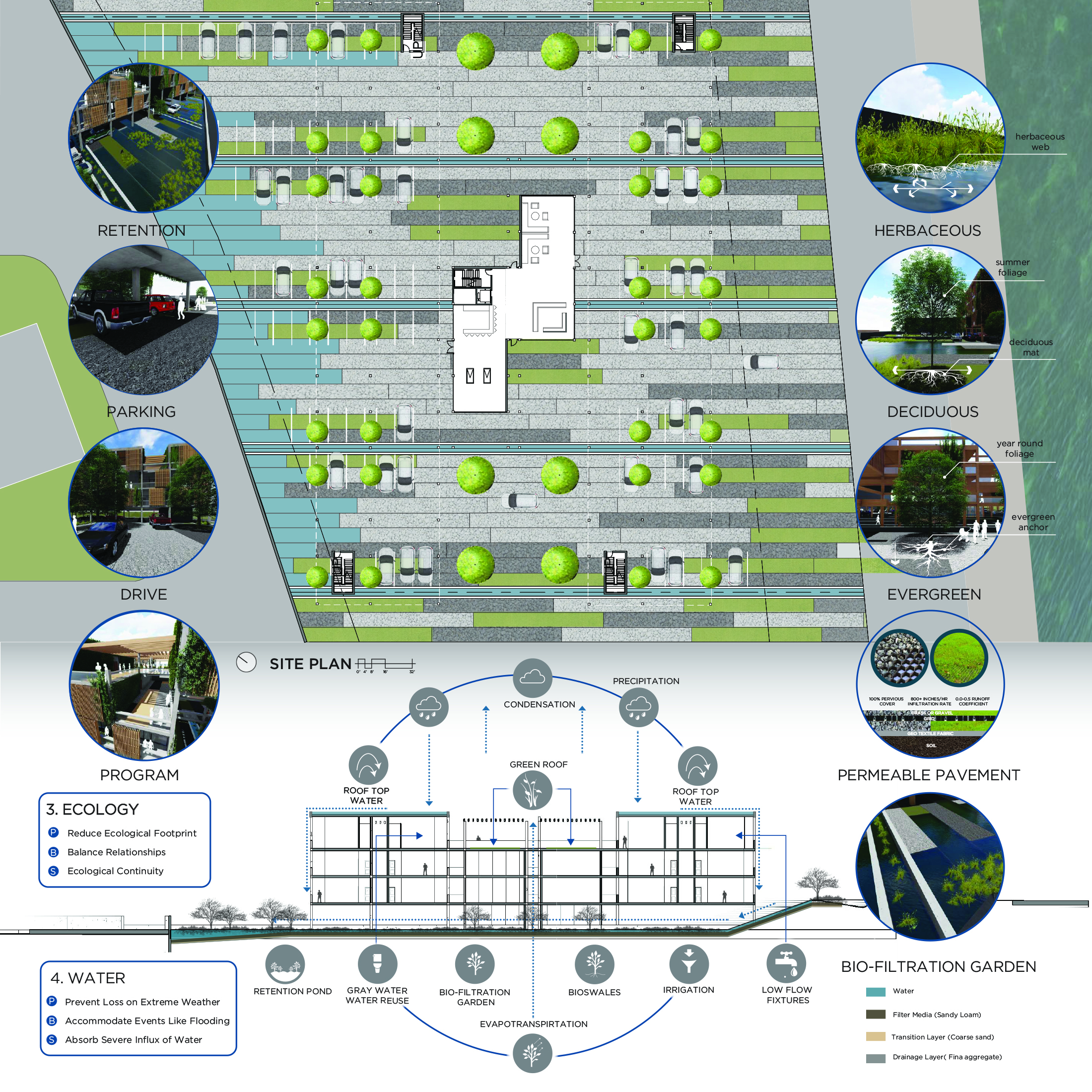

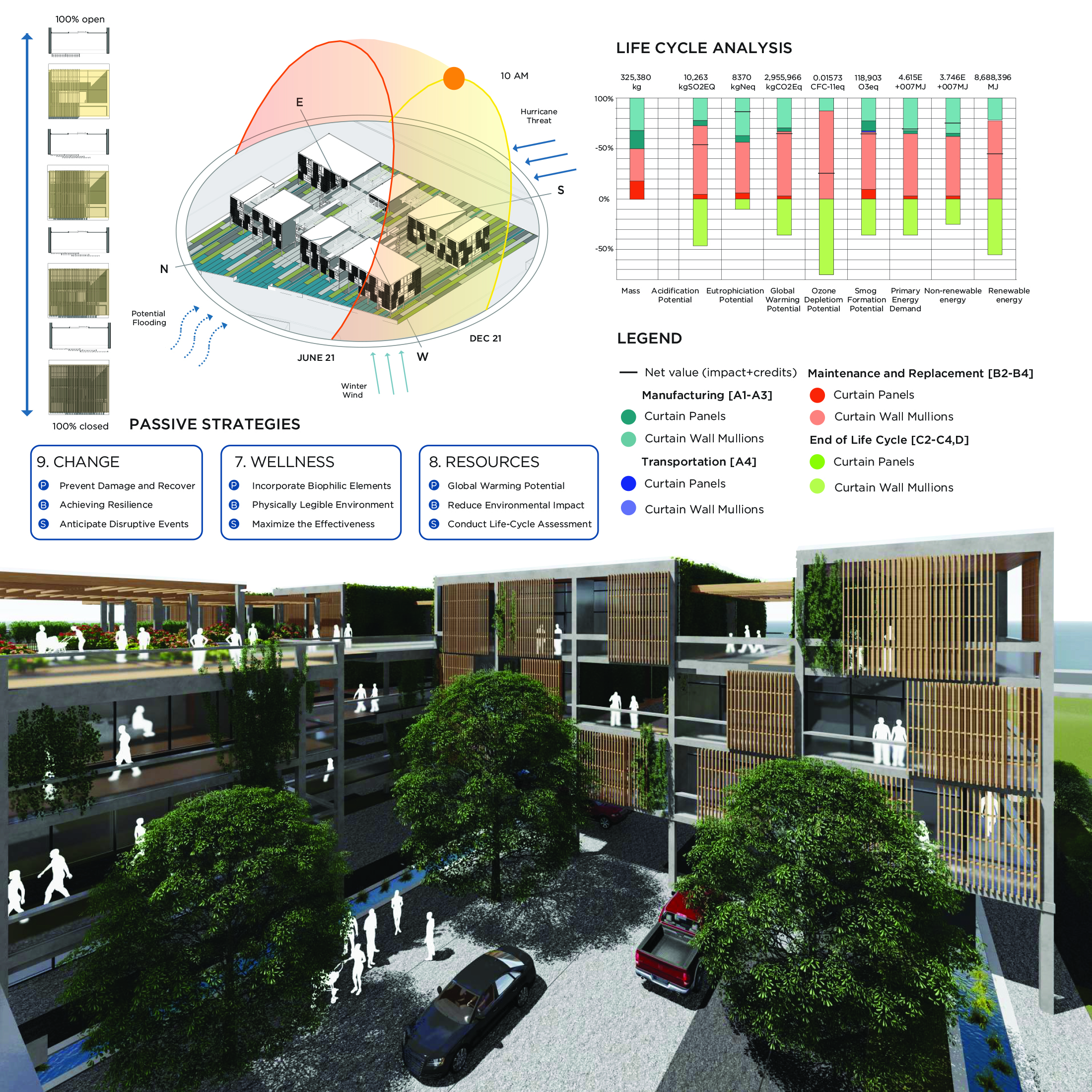

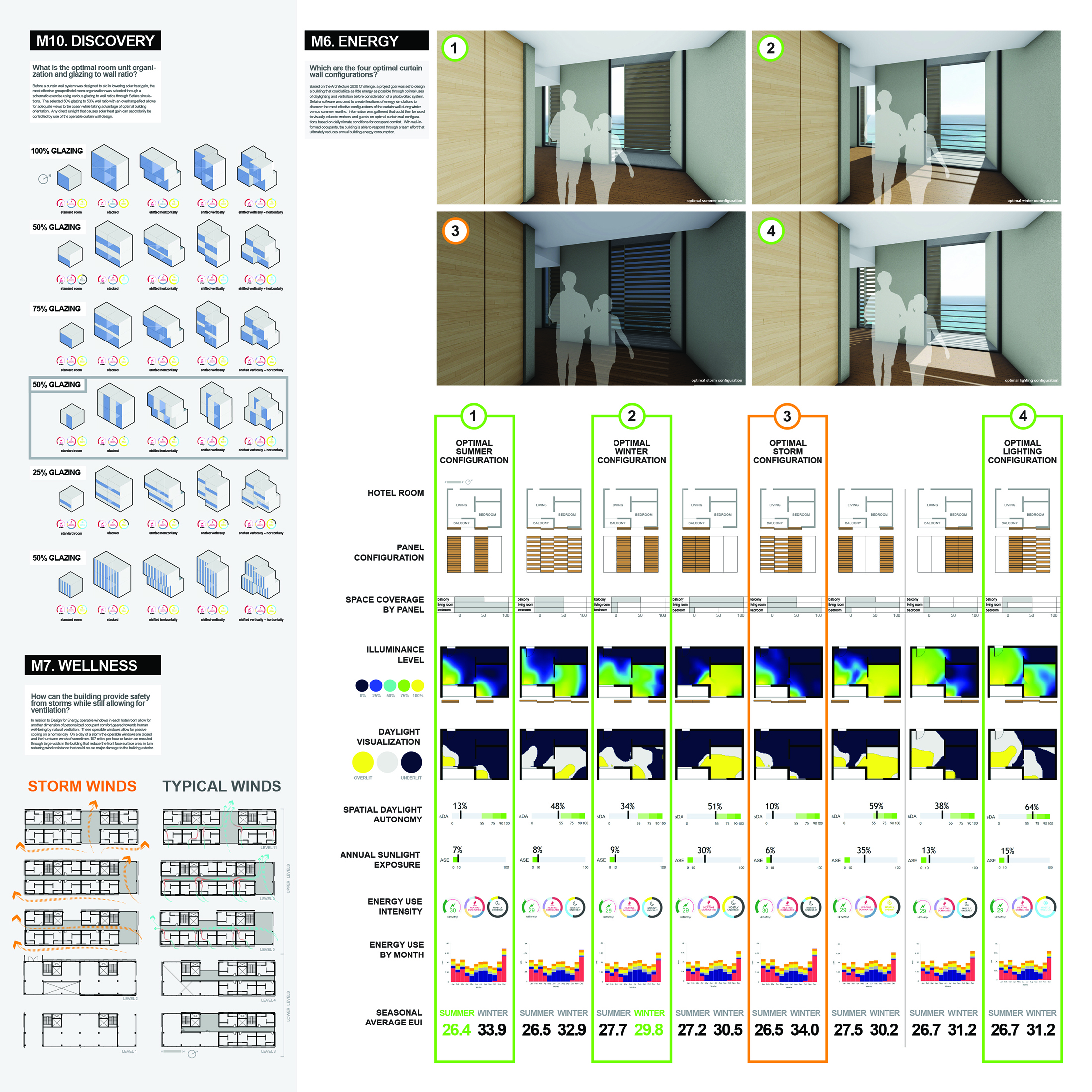

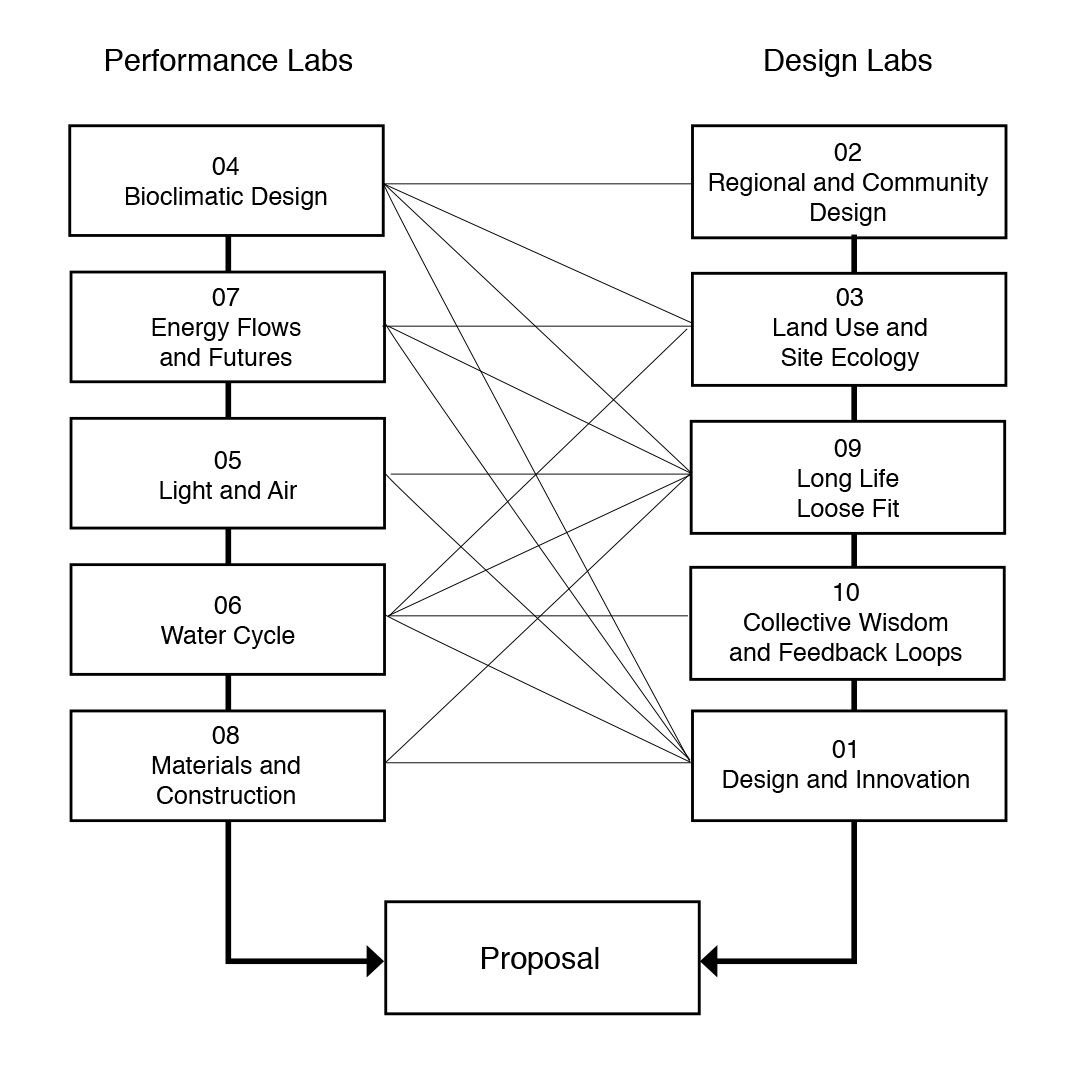

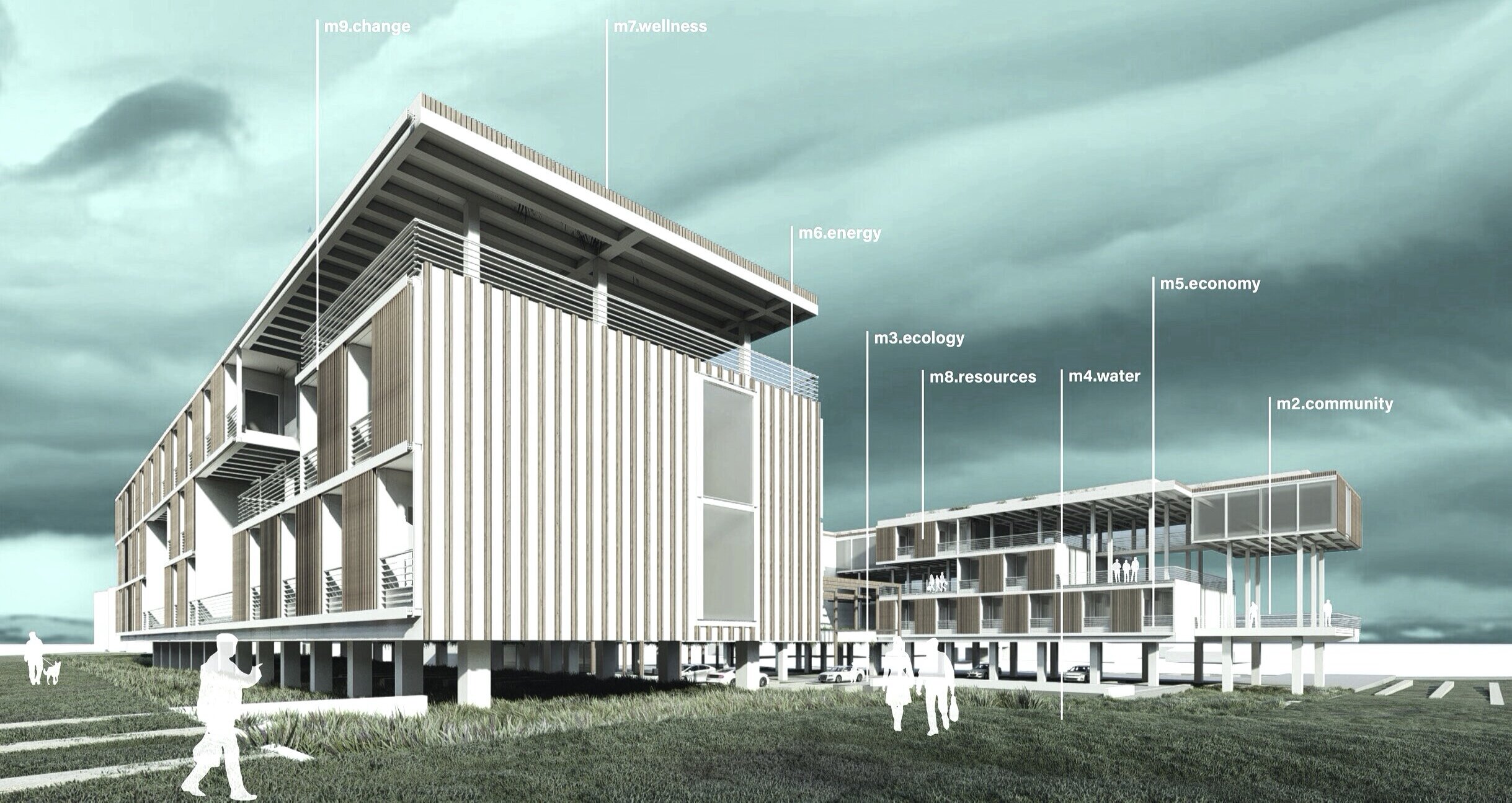

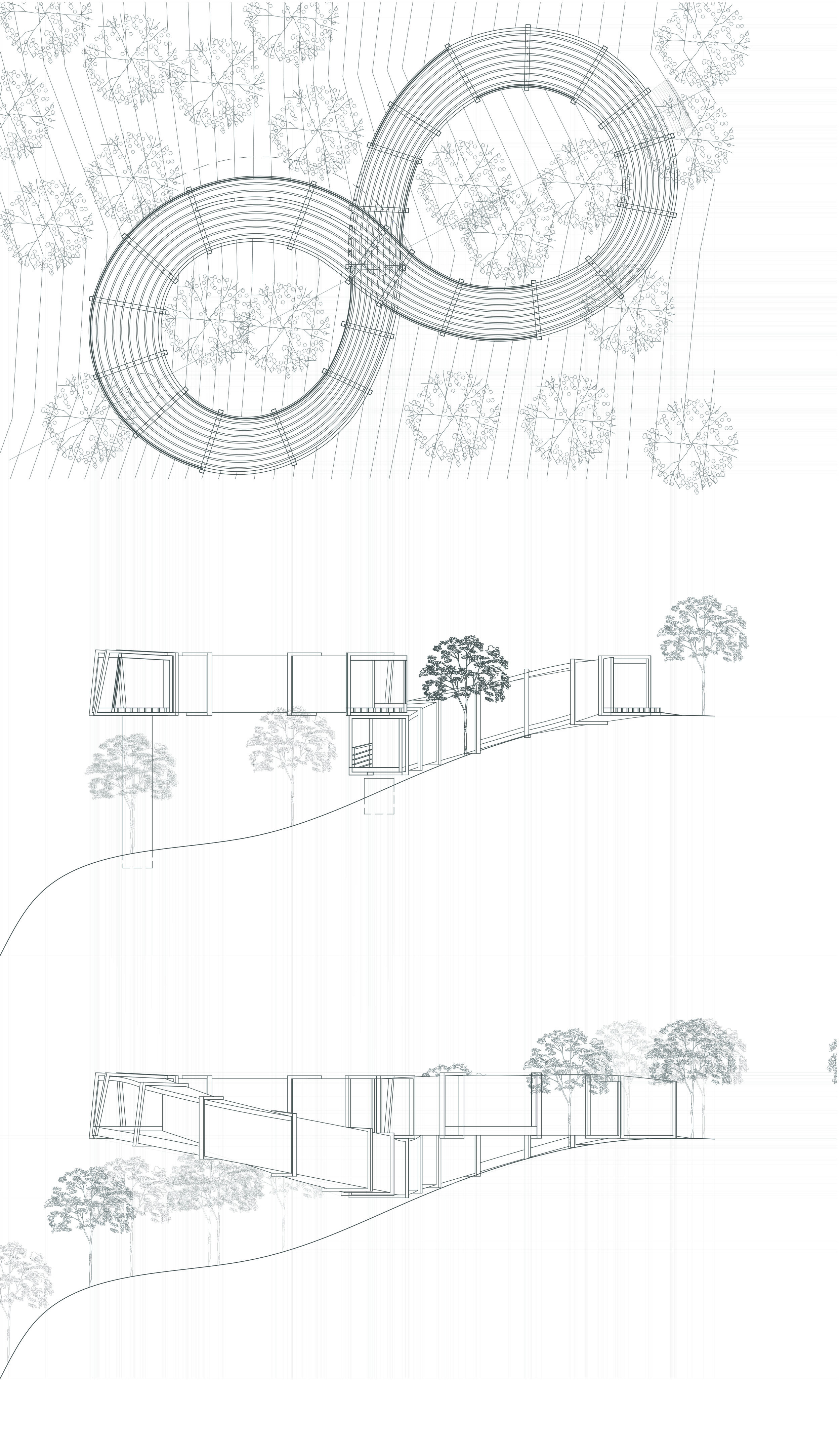

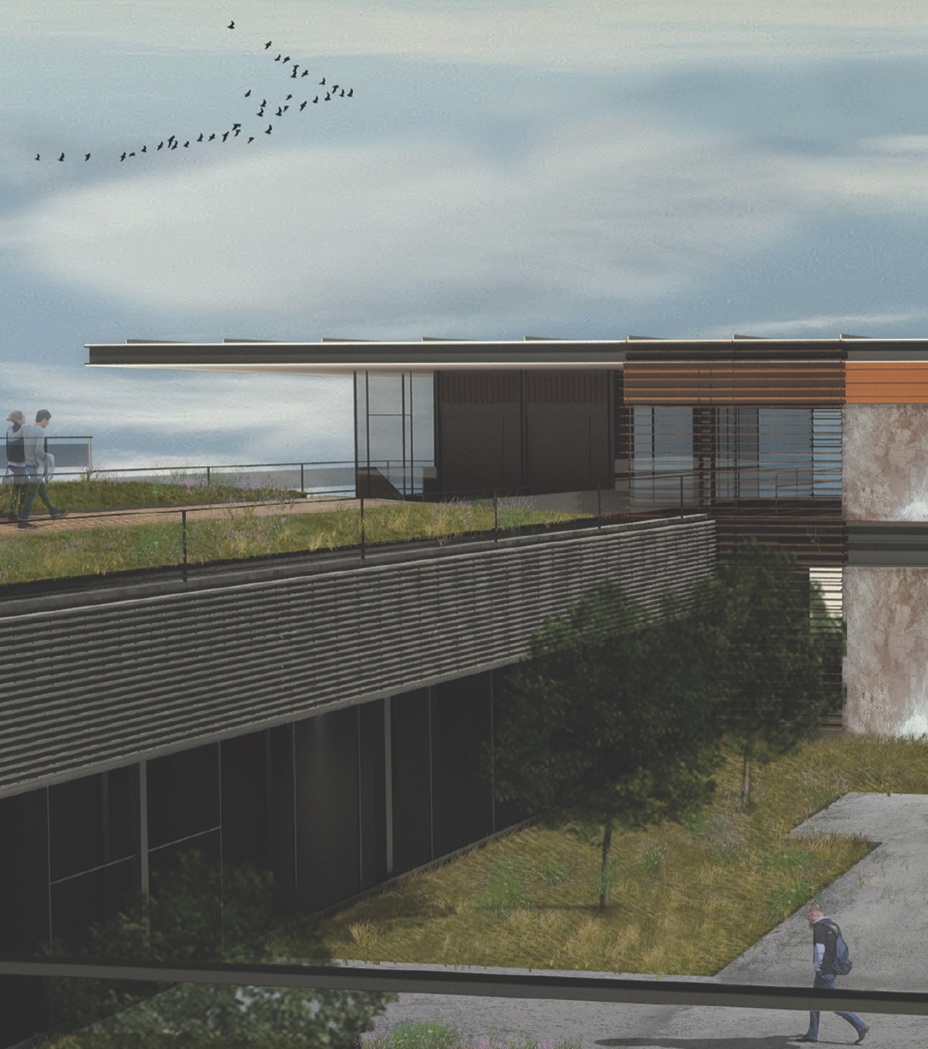

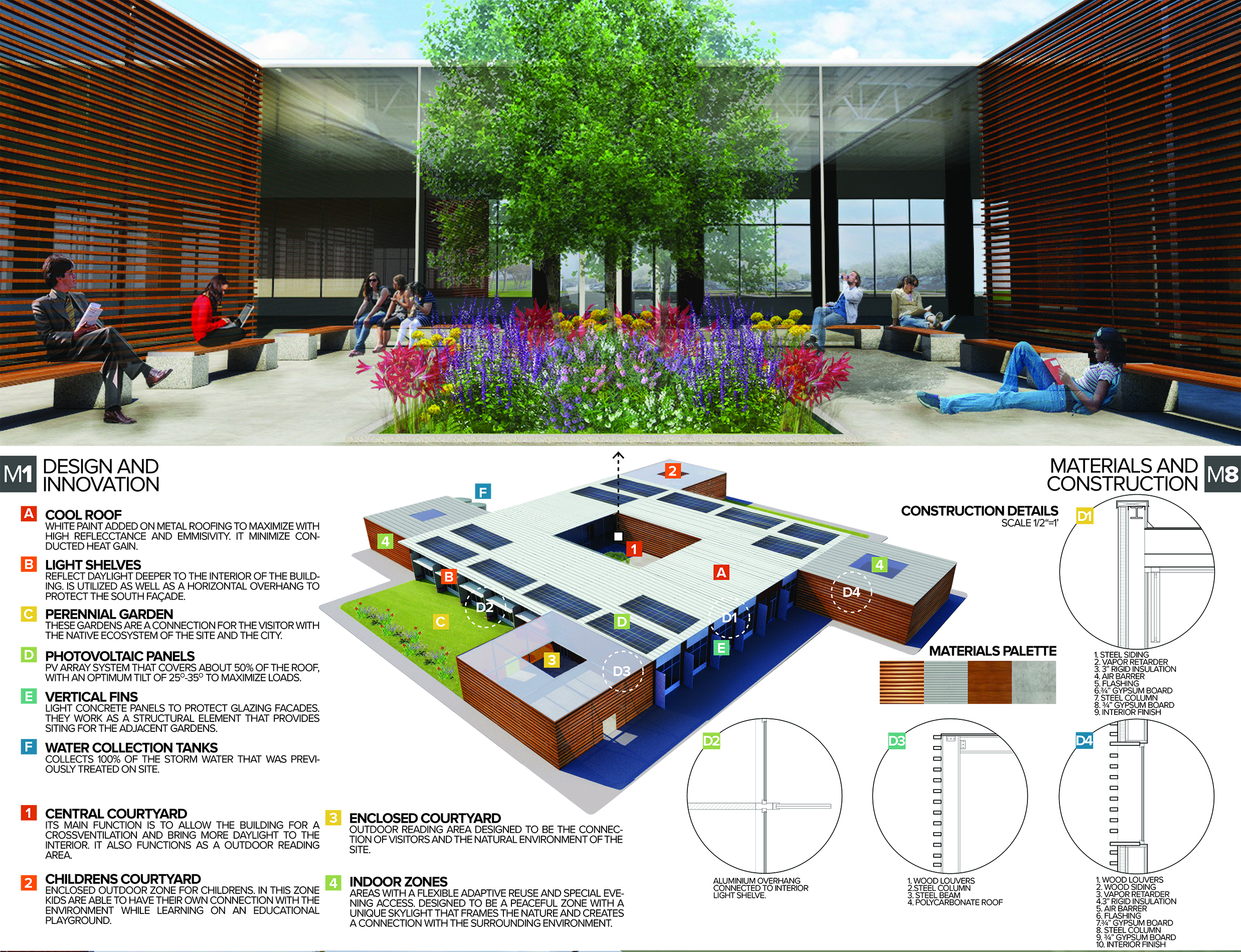

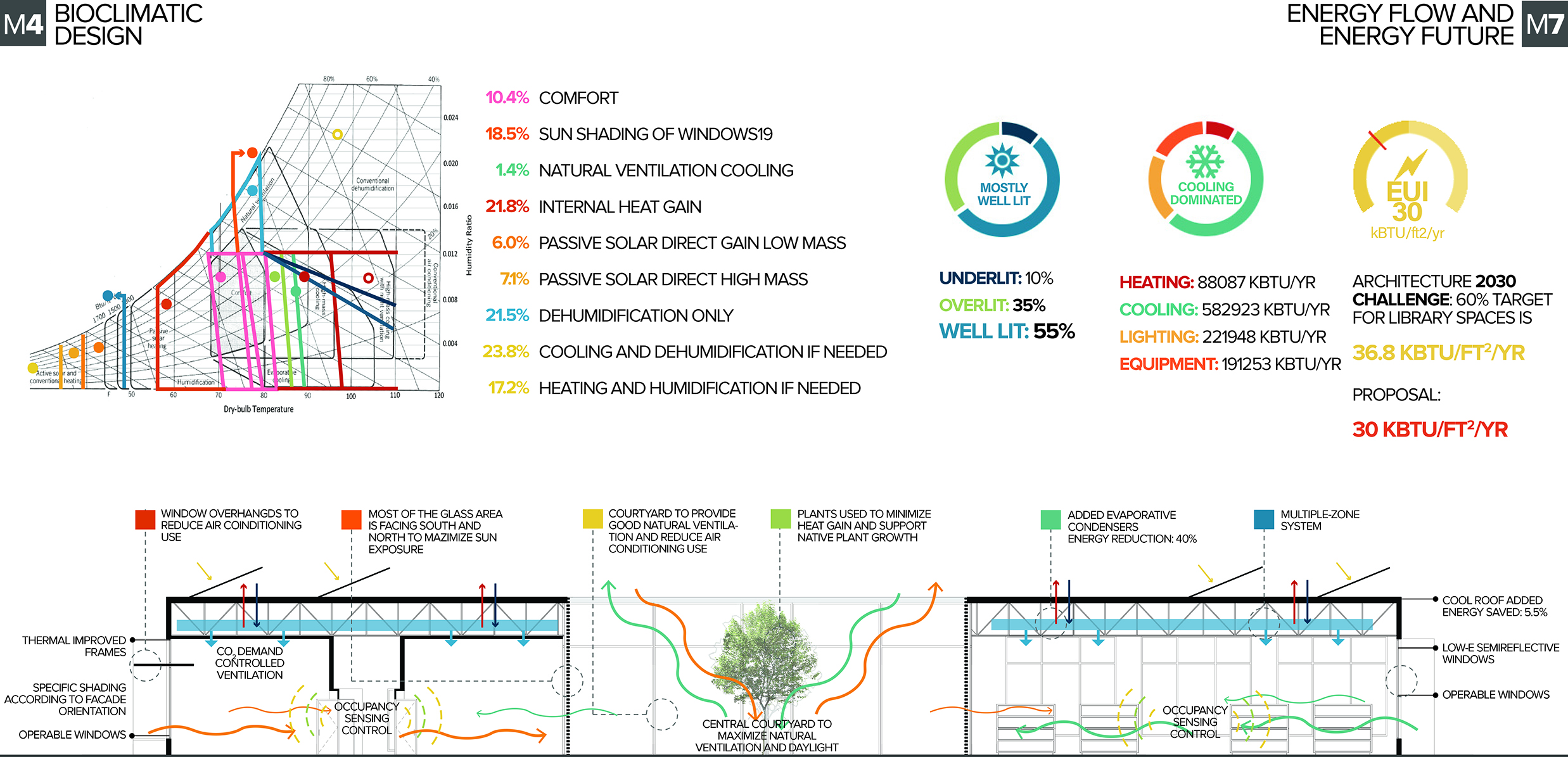

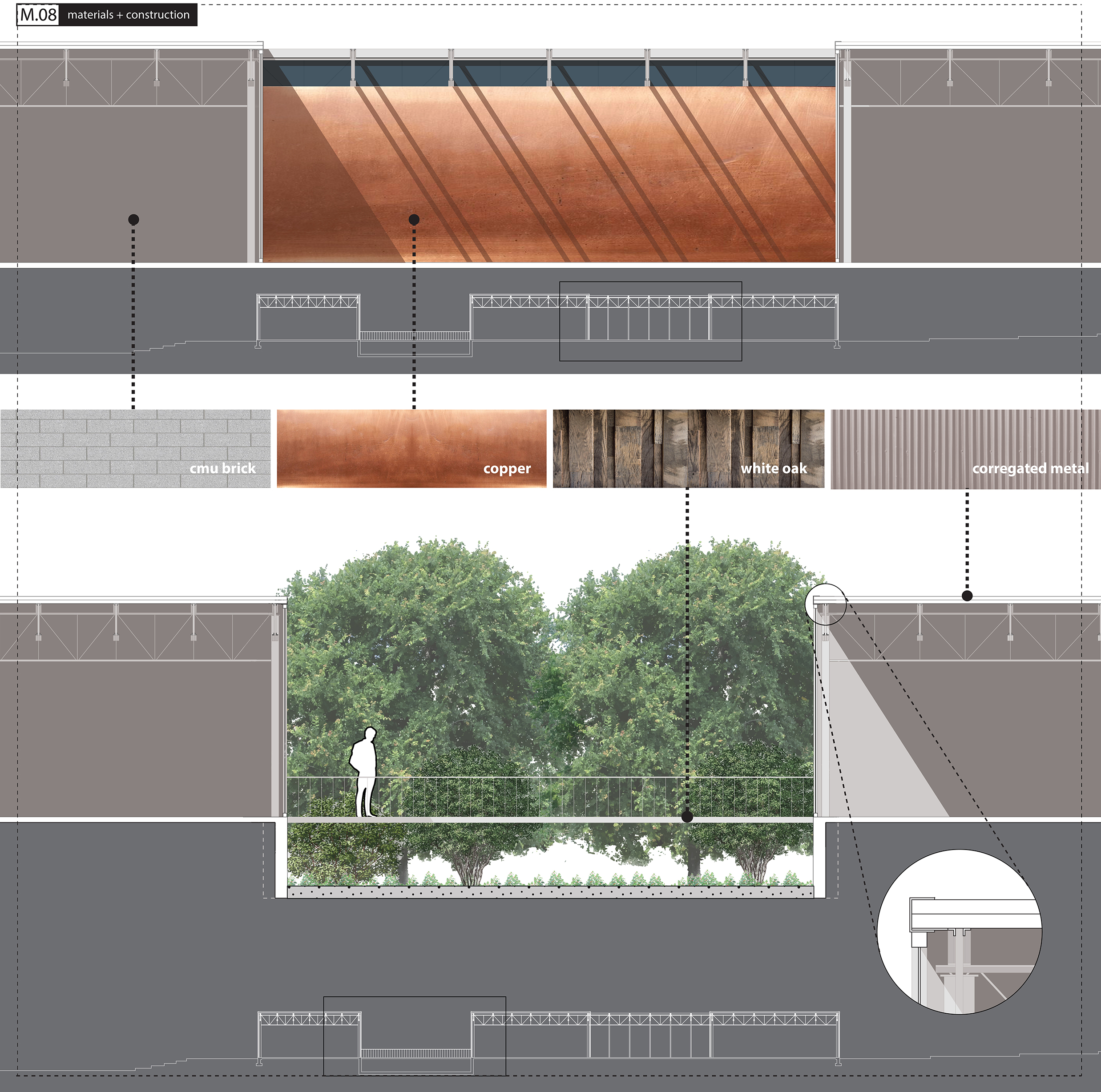

COTE Studio III-IV: Gulf Coast Resilience

University: UTSA

Type: Design Studio

Level: First Year Graduate

Co-Instructor: Dr. Hazem Rashed-Ali

Student Designers: Patricia Guerra and Molly Padilla, Ivan Ventura Gonzalez and Andre Simon

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

This graduate studio seeks to embed issues of ecological literacy and resilience into a traditional studio setting through the comprehensive integration of advanced performance metrics and design pedagogy. The two studio instructors—one with expertise in building performance and the other in architectural design—will initiate a critical feedback loop, creating dialogue between issues of analysis and design, performance and form. The studio will pursue these critical topics in parallel, with the goal of fully exploring the oft-misunderstood relationship between architectural sustainability and aesthetics.

To this end, the studio will embrace the goals and methods of the Architecture 2030 Challenge,which commits that all new buildings and major renovations will be carbon-neutral by 2030. The studio will specifically focus on the design of a eco-hotel in one of the beautiful and ecologically harsh environments in the State of Texas: Galveston Island.

Our learning objectives are as follows:

1. Develop methods to improve architectural resilience and rapid recovery in face of natural disasters and shock events

2. Advance the design of a carbon neutral built environment, in accordance with the Architecture 2030 Challenge

3. Embed issues of ecological literacy into traditional studio setting

4. Create a critical feedback loop between issues of building performance and design

5. Embed advanced performance modeling and metrics into traditional studio setting

6. Provide students with the opportunity to enter an international design competition

BALANCING EXTREMES

This semester the studio will investigate the critical topic of environmental sustainability, with a specific focus on issues of energy efficiency, adaptability, and resilient design. Resilient design is “...the intentional design of buildings, landscapes, communities, and regions in order to respond to natural and manmade disasters and disturbances—as well as long-term changes resulting from climate change—including sea level rise, increased frequency of heat waves, and regional drought [2].”

The location for our work is the site of the deadliest natural disaster in United States history: Galveston, Texas. On September 7, 1900 Galveston was a bustling port city on the Gulf Coast and the center of cotton trade in Texas. On September 8, a devastating hurricane swept through the Galveston, killing between 6,000 and 8,000 thousand residents (about one-fifth of the town) and dramatically altering the island’s historical trajectory. Galveston would eventually recover physically, rebuilding the lost urban fabric and constructing a ten-mile long and seventeen foot-high seawall to protect the island’s southern exposure. Still, the city never regained its position as a preeminent port of entry for the southern U.S., a function assumed by the Port of Houston.

Today, Galveston exists as a successful resort city with a population of 50,000, and a popular weekend getaway for Houston residents. While shipping is still integral to the port city, Galveston’s economy has diversified to include tourism, health care, finance, and education. Despite Galveston’s physical recovery, and subsequent reinvention as a tourist destination, the reality of life in Galveston continues to be defined by the precarious geography and fragile ecology of the barrier island. To live in Galveston, therefore, requires navigating life

between ocean and bay,

between tourism and trade,

betwen mansion and cottage,

between leisure and disaster,

and ultimately between safety and danger.

As one writer recently observes:

“Most of the fast-food joints, bars and hotels look hurriedly thrown up by people suspecting it’s not worth taking much care because they’ll have to do it all over again soon.... But head to the fine homes and commercial buildings in the restored historic district near the port and it’s easy to imagine how Galveston must have looked in its Victorian heyday [3].”

Another resident explains:

“We get riding high like we are right now then we get another hurricane that knocks the socks right off of us, then we’re down in the depths of ‘how are we gonna recover, will we recover....”

Such trials and contradictions continue to define life on the island, which is still impacted by the psychic trauma of 1900. As we begin our semester’s work on August 25, 2017, Galveston residents are carefully watching the path of Hurricane Harvey, which they suspect will become the first storm to threaten the Gulf Coast since Hurricane Ike in 2008. Such natural disasters will only increase in frequency and intensity, as temperatures and sea levels continue to rise as a result of human-induced climate change resulting from C02 emissions. In light of such dramatic historical, current, and future environmental challenges, Galveston residents must find a way to reconsider and redefine their geographic and urban circumstances.

“We underattend to the future, we too quickly forget the past and we too readily follow the lead of people who are no less myopic than we are.”— Robert Meyer, a professor of marketing at the University of Pennsylvania in response to Superstorm Sandy [4]

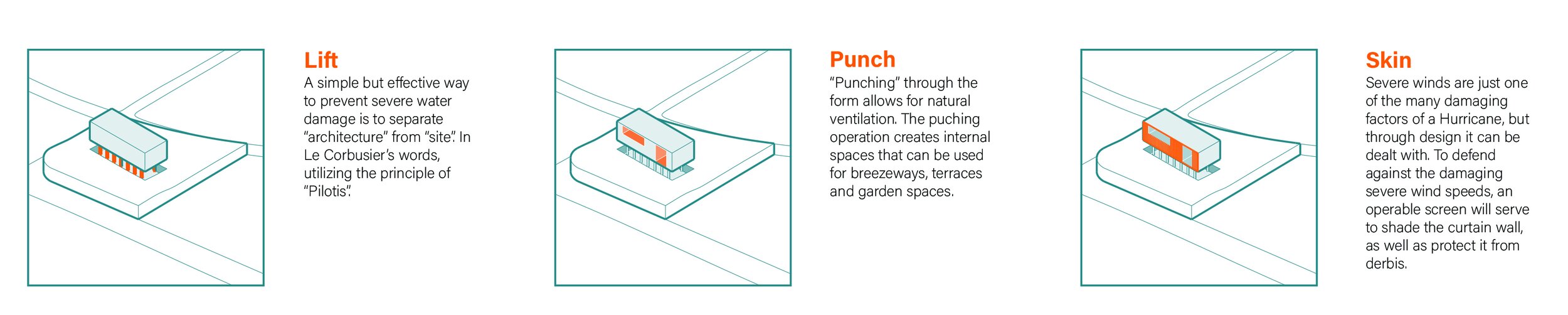

Our charge this semester is to develop an architecture that remembers the past, while confidently and creatively attending to the future. The studio will pursue this goal through the design of a single structure, located along Galveston’s most historically precarious site: the Gulf Coast seawall. The structure, a hotel that caters to eco-tourists, will seek to mediate the extreme environmental circumstances that define Galveston today, while searching for an architecture of efficiency, adaptability, and resilience. For studio designers, this means developing a form that

weathers the increasingly severe storms that roll in from the Gulf,

redefines the program, function, and image of twenty-first century tourism,

achieves a powerful and refined architectural expression using limited material resources,

redefines the program, function, and image of twenty-first century leisure,

and makes residents feel safe.

In order to accomplish these ambitious goals, we will utilize a systemic approach to design to emphasizes the interdependence of parts, while continually questioning the boundaries of our work. We will simultaneously subscribe to the following systemic principles of resilient design [5]:

resilient systems transcend scales

resilient systems provide for fundamental human needs

resilient systems are diverse and redundant

resilient systems are simple, passive, and flexible

resilient systems are durable

resilient systems are local, renewable, and reclaimed

resilient systems anticipate interruptions

resilient systems learn from and leverage existing natural systems

resilient systems consider social equity and community

resilient systems are never absolute

Re-examining the Relationship between Form and Sustainability. As the studio aims to balance the complex ecologies of Galveston, it also aims to clarify the complex and often misunderstood relationship between architectural form and sustainability. Specifically, we will pursue the topic of sustainability as a form generator, not a technical overlay. To accomplish this goal, we will model our design process on a highly structured feedback loop that takes into account issues of design and analysis, form and performance. We will always pursue these critical topics in parallel; never in isolation. This means that initial formal impulses must answer to feedback from simulation and software.

A similar dialogue will take place between the two studio instructors, with Professor Rashed-Ali advocating for performance and sustainability and Professor Caine emphasizing architectural and site issues. In the end, the instructors and issues will inform each other, while the responsibility for final design decisions will rest solely with the students. This robust dialogue will commence with initial sketches and continue until final renderings and models are complete.

Ultimately, all proposals must account for the fact that the built environment is a key contributor to a host of environmental pollutants, including the carbon emissions associated with global warming. This studio therefore requires designers to minimize the environmental impact associated with their building and site proposals. This will require each student to simultaneously attend to multiple aspects of site and building design including water use, energy use, resource consumption, occupant comfort and daylighting. At the conclusion of the semester, students must deliver a proposal that is formally dynamic, environmentally efficient, programmatically compelling and that engages users at the scale of the site and building.

Modeling Performance. Dr. Rashed-Ali will introduce student designers to critical software packages, allowing them to leverage the latest technology to model building performance. The studio will focus on the following software packages extensively:

Climate Consultant: Developed by the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA), Climate Consultant enables users to understand, analyze, and visualize local climatic characteristics (i.e. temperature, relative humidity, solar insolation, wind patterns, sky cover) before selecting climate-responsive design strategies.

Sefeira: This software allows users to analyze design proposals, specifically with regard to energy and daylighting performance. It also enables users identify design characteristics that optimize energy and daylighting performance.

Athena Impact Estimator: The software allows students to evaluate the impact of design and materials on the environment (i.e. global warming potential, acidification potential).

AIA COTE Top Ten Competition for Students. “The American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment (AIA COTE), in partnership with the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), is pleased to announce the fourth annual AIA COTE Top Ten for Students, offered this year in collaboration with Architecture 2030 as INNOVATION 2030. The program challenges students, working individually or in teams, to submit projects that use a thoroughly integrated approach to architecture, natural systems, and technology to provide architectural solutions that protect and enhance the environment. The competition will recognize ten exceptional studio projects that seamlessly integrate adaptive, resilient, and strategies for moving towards carbon-neutral operation within their broader design concepts [8].”

AIA COTE Top Ten Criteria

Measure 1: Design for Integration

Measure 2: Design for Community

Measure 3: Design for Ecology

Measure 4: Design for Water

Measure 5: Design for Economy

Measure 6: Design for Energy

Measure 7: Design for Wellness

Measure 8: Design for Resources

Measure 9: Design for Change

Measure 10: Design for Discovery

[2] The Resilient Design Institute. www.resilientdesign.org/.

[3] Tom Dart, The Guardian, “Glen Campbell’s Galveston: politics of nostalgia echo amid faded grandeur,” 12 August 2017.

[4] The Resilient Design Institute. www.resilientdesign.org/.

[5] The Resilient Design Institute. www.resilientdesign.org/.

[8] AIA COTE Top Ten for Students: Innovation 2030. AIA Committee on the Environment Student Design Competition 2017-2018.

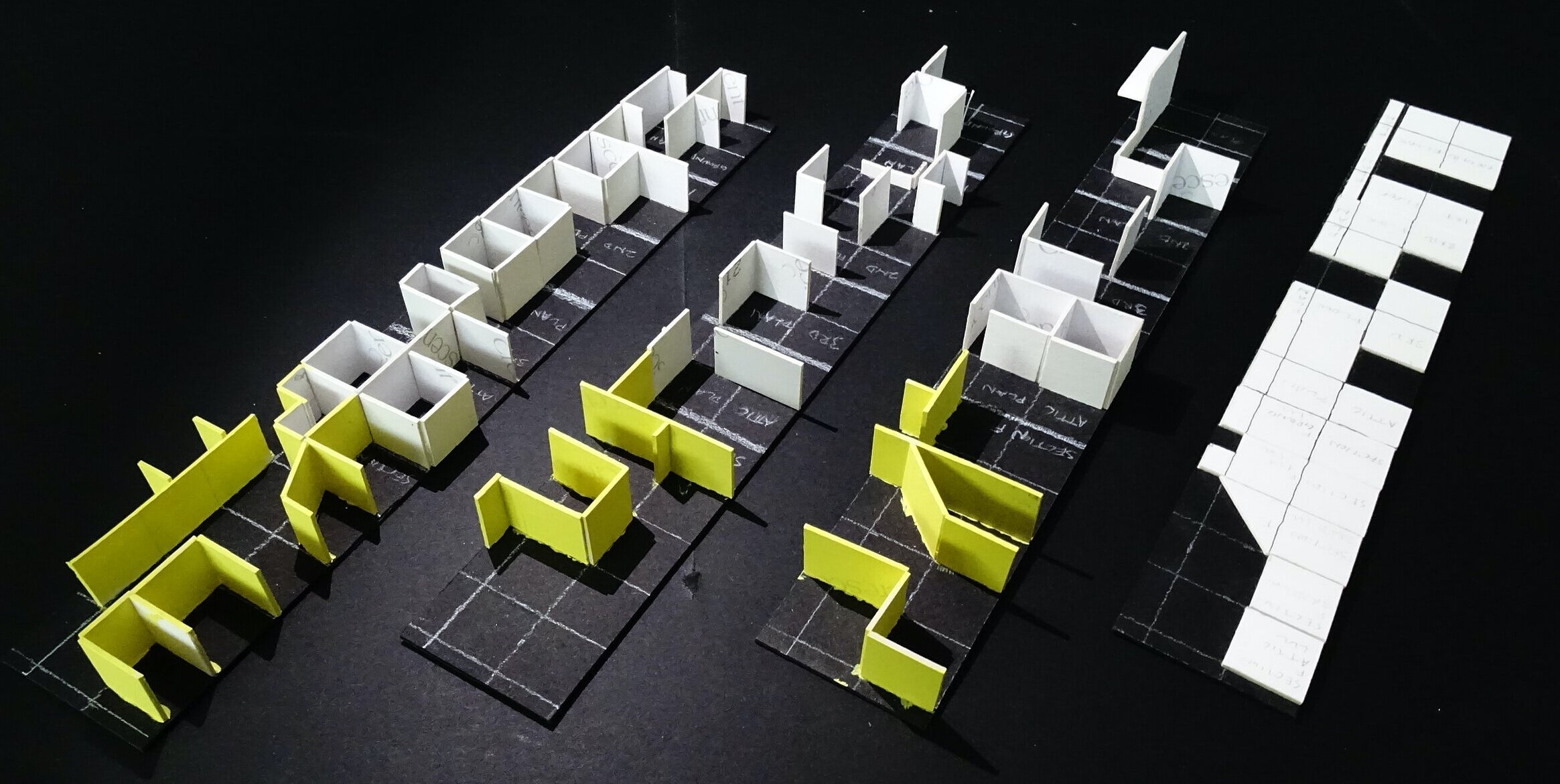

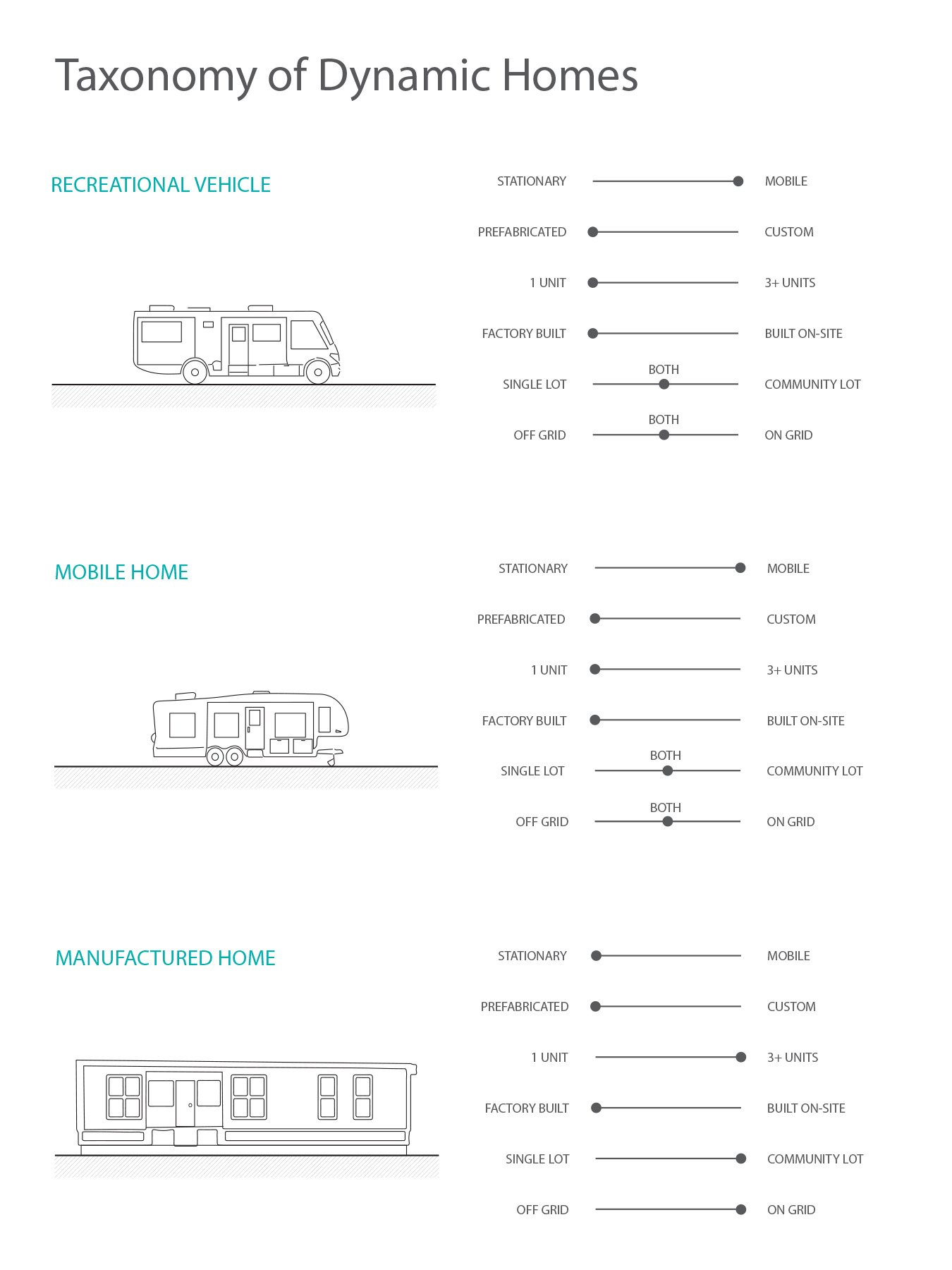

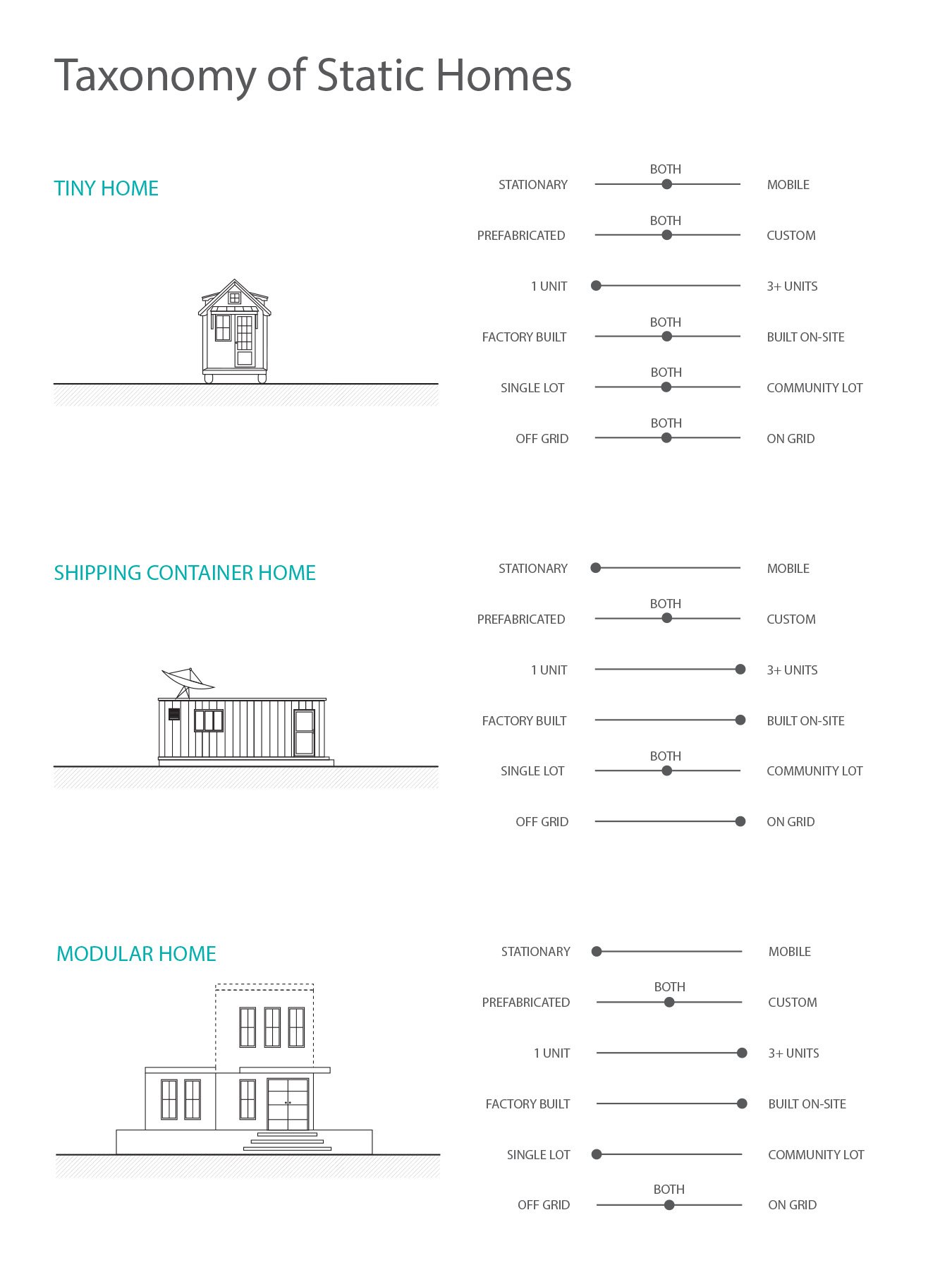

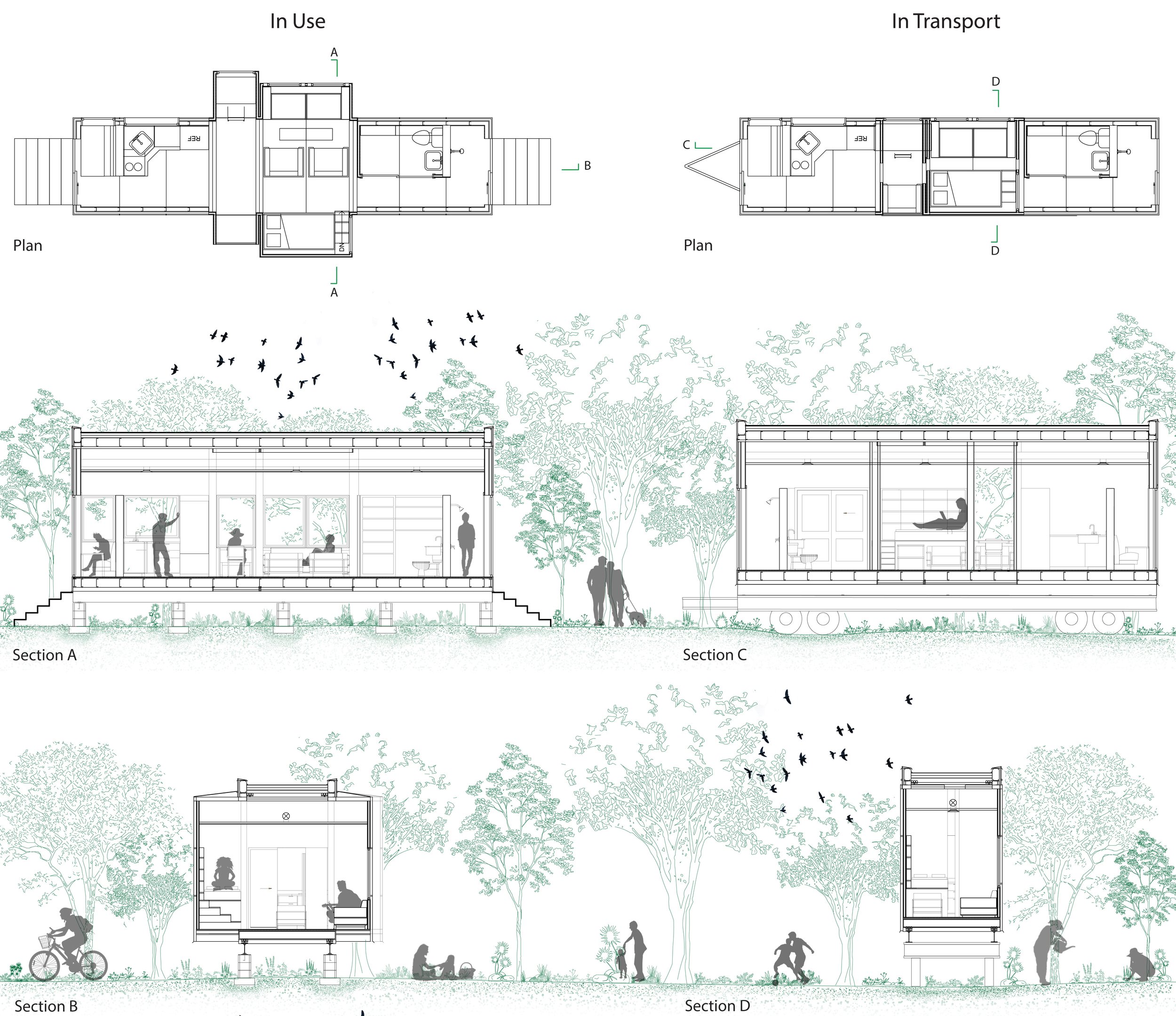

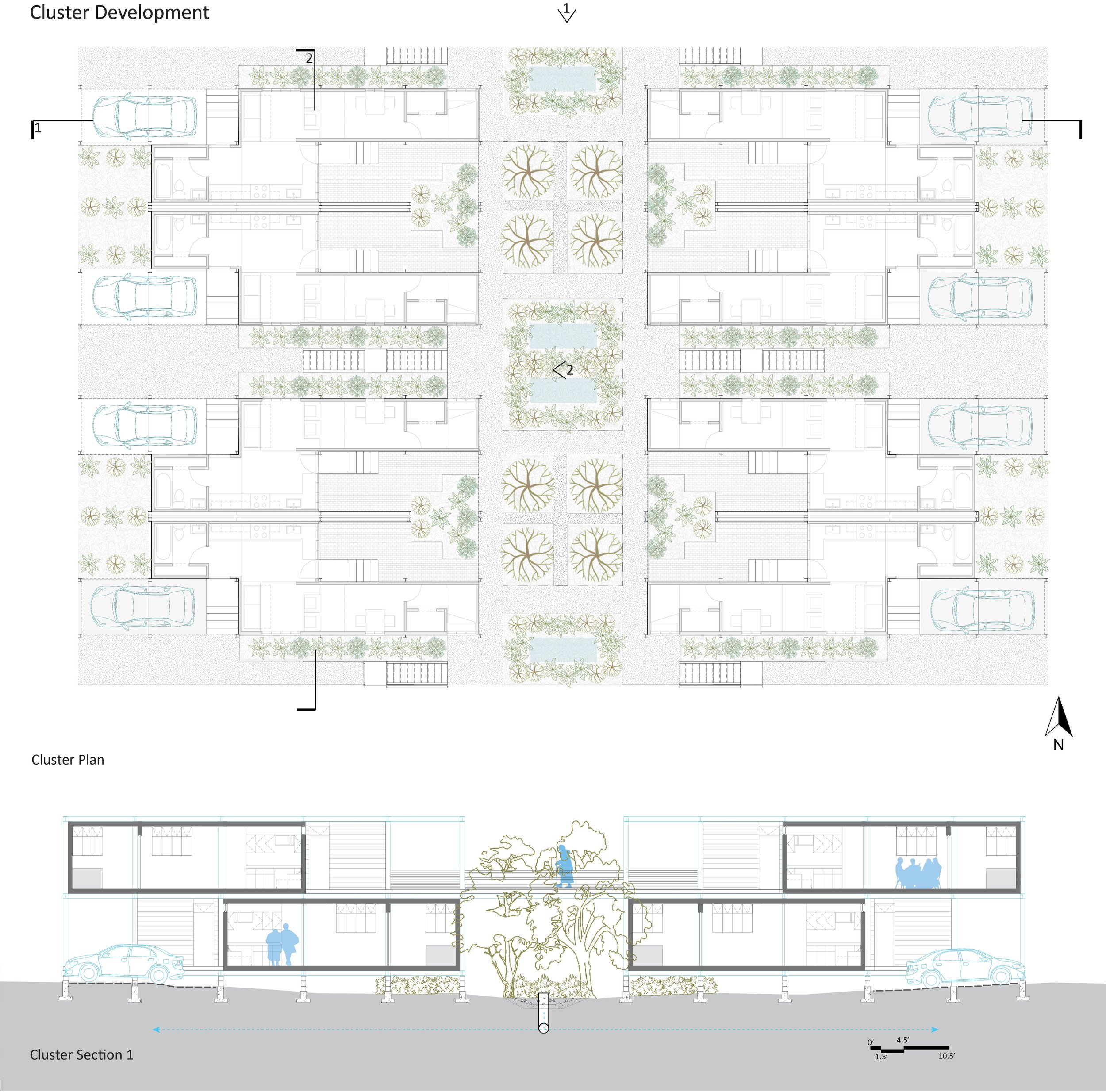

RAPID, MOBILE, SMALL, CHEAP: (RE) CONSTRUCTING THE ARCHITECTONICS OF MOBILE HOMES

University: UTSA

Type: Design Studio

Level: First Year Graduate

Co-Instructor: Gabriel Díaz Montemayor

Student Designers: Karla Ruiz, Emily Benton, Tiffany Vargas, Sarah Harvey, Emily Benton

[M]obility is not about erasing everything that exists, but adding to the infrastructure in a more environmentally sound way—a more intelligent way of inhabiting the landscape—resting lightly on the ground.

- Jennifer Siegal, Architect (2016)

This advanced graduate design studio will examine the topics of temporality, mobility, efficiency, and affordability as they relate to the production and occupation of manufactured housing in Texas. For decades manufactured homes, often referred to colloquially as mobile homes, have occupied a prominent if undefined place in the public imagination. Qualifying as neither traditional homes nor trailers, manufactured home communities occupy the vague conceptual terrain between

trailer park and subdivision,

vernacular and Modern,

temporary and permanent,

fragile and durable,

indeterminant and determinant,

landscape and building,

low and high culture,

local and global,

personal and collective,

specific and generic form.

For more than a century, mobile and manufactured homes have offered occupants an accessible and affordable alternative to traditional housing. As modular structures, mobile homes are 85-90% complete when they leave the factory. The first recreational vehicle (RV) in the United States dates to 1910, when the Touring Landau allowed drivers to hitch a RV to their car for $8,2050.

Today, manufactured housing represents a core residential typology in the United States, providing shelter for 20 million people or 6% of the U.S. population. The State of Texas leads the way, containing 108,282 manufactured housing units, far outstripping the State of Florida, which contains 38,792. Texas also leads the way in the production of manufactured housing, as 20 of the 124 manufactured home production plants in the United States are located in Texas.

In Weslaco, Texas–where this studio will focus its work¬–there are no fewer than a dozen mobile home and RV parks, many of which serve the “winter Texans” who migrate south for the warm weather and exceptional bird watching. The studio will specifically build on urban planning work that UTSA’s Center for Urban and Regional Planning Research is doing with the City of Weslaco, Texas, a medium-sized city of 41,000. Weslaco is located in Hidalgo County, the 7th largest and 11th fastest growing county in Texas between 2018-19. Hidalgo County comprises one of three counties in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, a transborder region is located in the floodplain of the Rio Grande River and adjacent to the Mexican State of Tamaulipas.

In order to gain an accurate and complete view of manufactured housing, the studio will examine the phenomenon broadly across scales, addressing the phenomenon within a cultural, regional, metropolitan, site, building, and finally a material context. At each scale, students will begin their design process with a brief but in-depth research exercise. Like the studio, these research exercises will transcend scale, addressing issues at the scale of the region and the scale of construction detail with equal seriousness. The purpose of the research exercises is to center the discussion of knowledge, precedent, and context in the studio discourse.

This site scales will be facilitated via two landscape workshops led by Gabriel Diaz Montemayor, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Arkansas.

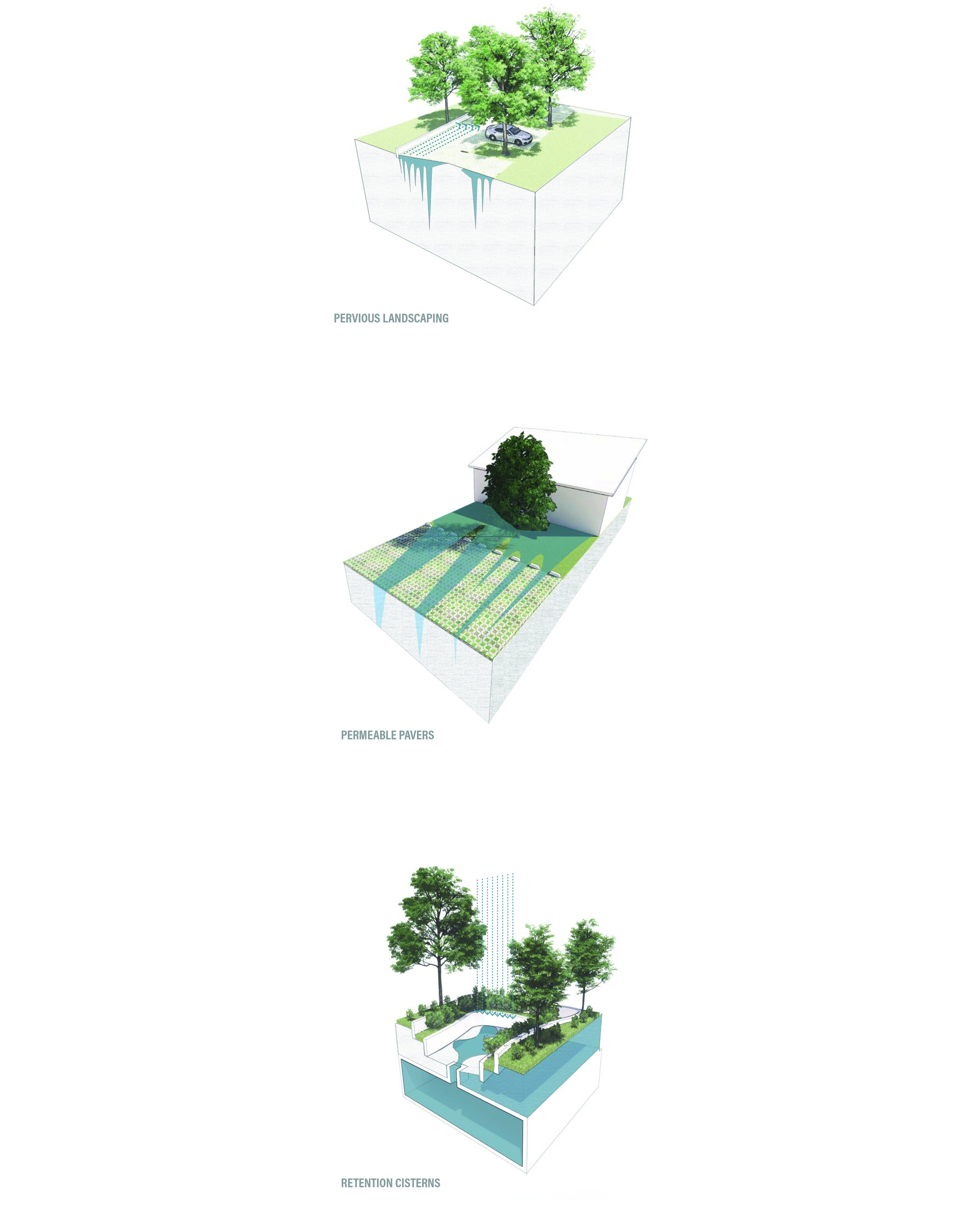

Workshop I Cluster Scale:

The scale of the cluster will allow students to begin considering issues of landscape and open space in the context of minimum-small scale-housing and critical socio-economic conditions. This one-week exercise will address the potential to trigger social and environmental ecotonal dynamics through the design of housing units and clusters. By examining case studies and readings, students will consider the design of social relational systems of spatial appropriation, i.e. how to foster and incentivize a sense of community and stewardship.

The medium for this will address environmental systems as they pertain to “siting on site” (grounding and landform), outdoor spatial definition, water management and flood prevention/response, solar orientation, natural ventilation, growing medium, and planting. The workshop will reflect on the spatial transitions from the private to the public, from the personal to the community, and consider how these can be set by employing various landscape architecture and infrastructure techniques.

Workshop II Urban Landscape Scale:

This scale privileges issues of urban landscape infrastructure, building aggregation, and collective programs. Each student will propose a formal prototype for a Modular Subdivision that addresses the arrangement of site infrastructure as well as mixed-use programming.

This one-week exercise will emphasize the same social and environmental ecotonal foundations as Workshop I, projecting the knowledge to an urban scale. The second workshop will expand on the qualities and capacities related to dynamic systems specific to the potential of mobile home communities to impact larger social, cultural, territorial, and natural conditions. The change in scale will facilitate the inclusion and engagement of various landscape infrastructure systems with the ability to integrate with the larger urban and natural landscape. Students will explore the capacity of spatial, mobility, and water systems to inform larger urban design responses.

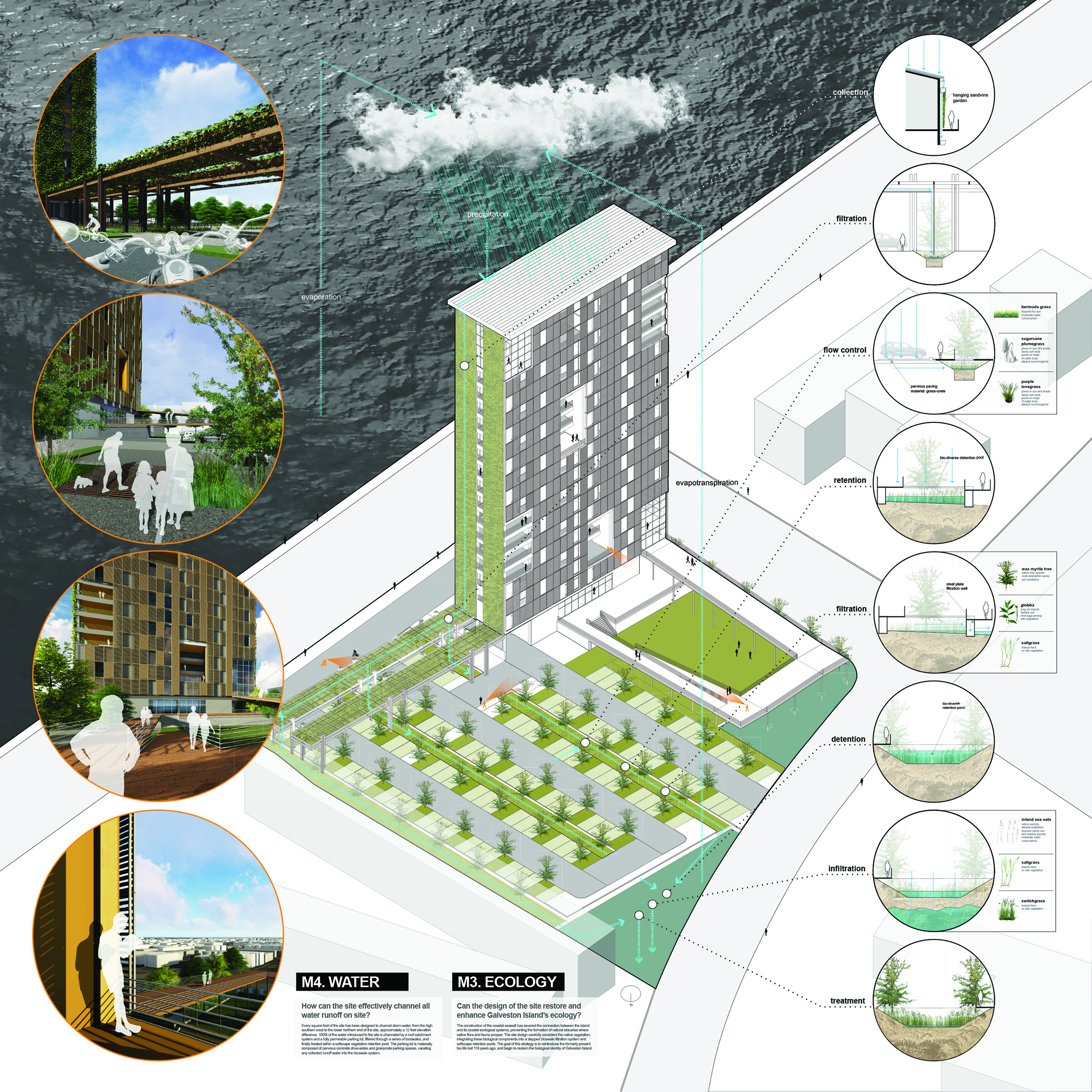

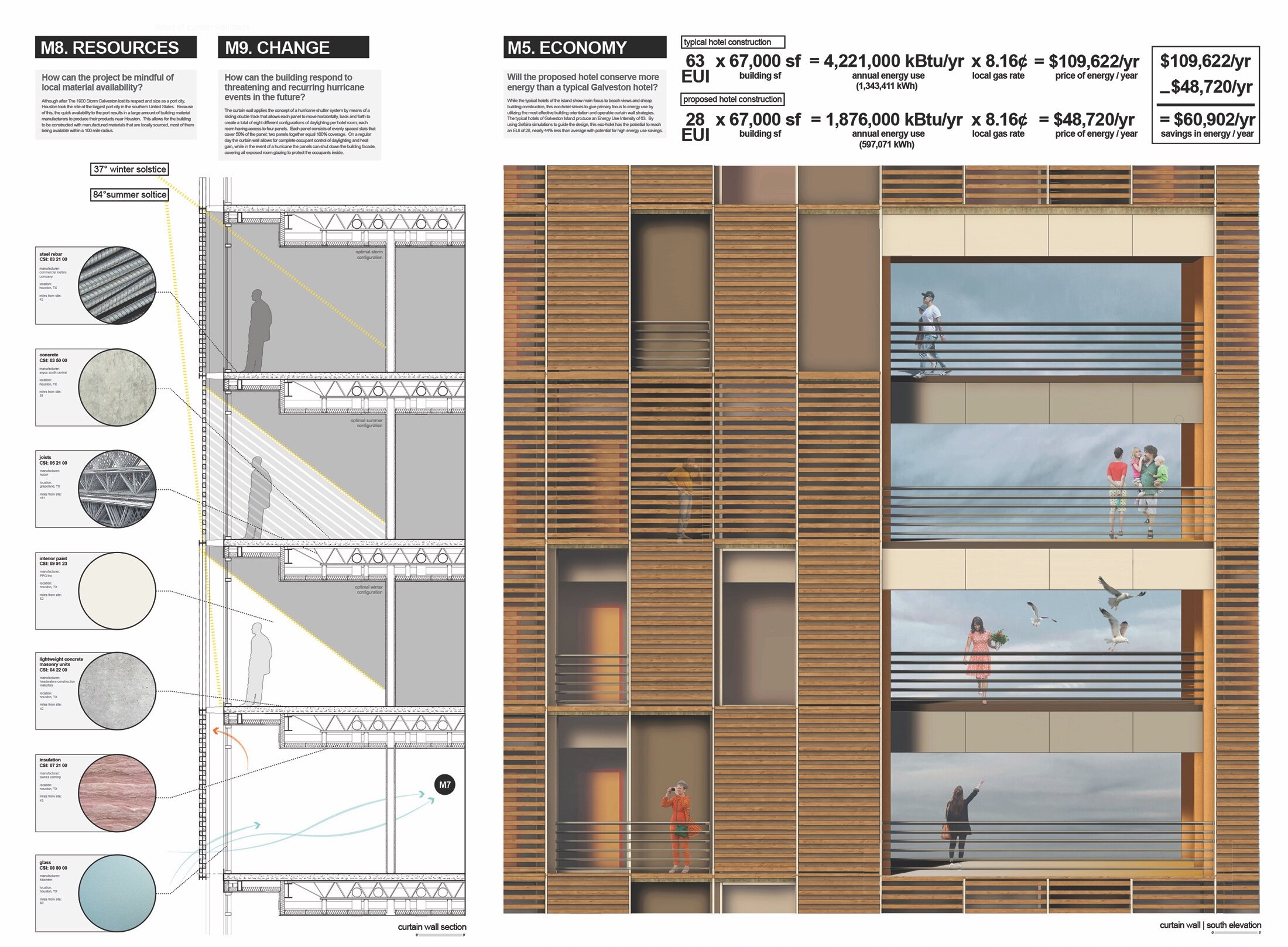

COTE Studio V: Gulf Coast Resilience

University: UTSA

Type: Design Studio

Level: Undergraduate

Co-Instructor: Dr. Hazem Rashed-Ali

Student Designers: Angel Mora + Mark Morin, Christian Garcia + Joe Valadez

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

This undergraduate studio seeks to embed issues of ecological literacy and resilience into a traditional studio setting through the comprehensive integration of advanced performance metrics and design pedagogy. The two studio instructors—one with expertise in building performance and the other in architectural design—will initiate a critical feedback loop, creating dialogue between issues of analysis and design, performance and form. The studio will pursue these critical topics in parallel, with the goal of fully exploring the oft-misunderstood relationship between architectural sustainability and aesthetics.

To this end, the studio will embrace the goals and methods of the Architecture 2030 Challenge,which commits that all new buildings and major renovations will be carbon-neutral by 2030. The studio will specifically focus on the design of a eco-hotel in one of the beautiful and ecologically harsh environments in the State of Texas: Galveston Island.

Our learning objectives are as follows:

1. Develop methods to improve architectural resilience and rapid recovery in face of natural disasters and shock events

2. Advance the design of a carbon neutral built environment, in accordance with the Architecture 2030 Challenge

3. Embed issues of ecological literacy into traditional studio setting

4. Create a critical feedback loop between issues of building performance and design

5. Embed advanced performance modeling and metrics into traditional studio setting

6. Provide students with the opportunity to enter an international design competition

BALANCING EXTREMES

This semester the studio will investigate the critical topic of environmental sustainability, with a specific focus on issues of energy efficiency, adaptability, and resilient design. Resilient design is “...the intentional design of buildings, landscapes, communities, and regions in order to respond to natural and manmade disasters and disturbances—as well as long-term changes resulting from climate change—including sea level rise, increased frequency of heat waves, and regional drought [2].”

The location for our work is the site of the deadliest natural disaster in United States history: Galveston, Texas. On September 7, 1900 Galveston was a bustling port city on the Gulf Coast and the center of cotton trade in Texas. On September 8, a devastating hurricane swept through the Galveston, killing between 6,000 and 8,000 thousand residents (about one-fifth of the town) and dramatically altering the island’s historical trajectory. Galveston would eventually recover physically, rebuilding the lost urban fabric and constructing a ten-mile long and seventeen foot-high seawall to protect the island’s southern exposure. Still, the city never regained its position as a preeminent port of entry for the southern U.S., a function assumed by the Port of Houston.

Today, Galveston exists as a successful resort city with a population of 50,000, and a popular weekend getaway for Houston residents. While shipping is still integral to the port city, Galveston’s economy has diversified to include tourism, health care, finance, and education. Despite Galveston’s physical recovery, and subsequent reinvention as a tourist destination, the reality of life in Galveston continues to be defined by the precarious geography and fragile ecology of the barrier island. To live in Galveston, therefore, requires navigating life

between ocean and bay,

between tourism and trade,

betwen mansion and cottage,

between leisure and disaster,

and ultimately between safety and danger.

As one writer recently observes:

“Most of the fast-food joints, bars and hotels look hurriedly thrown up by people suspecting it’s not worth taking much care because they’ll have to do it all over again soon.... But head to the fine homes and commercial buildings in the restored historic district near the port and it’s easy to imagine how Galveston must have looked in its Victorian heyday [3].”

Another resident explains:

“We get riding high like we are right now then we get another hurricane that knocks the socks right off of us, then we’re down in the depths of ‘how are we gonna recover, will we recover....”

Such trials and contradictions continue to define life on the island, which is still impacted by the psychic trauma of 1900. As we begin our semester’s work on August 25, 2017, Galveston residents are carefully watching the path of Hurricane Harvey, which they suspect will become the first storm to threaten the Gulf Coast since Hurricane Ike in 2008. Such natural disasters will only increase in frequency and intensity, as temperatures and sea levels continue to rise as a result of human-induced climate change resulting from C02 emissions. In light of such dramatic historical, current, and future environmental challenges, Galveston residents must find a way to reconsider and redefine their geographic and urban circumstances.

“We underattend to the future, we too quickly forget the past and we too readily follow the lead of people who are no less myopic than we are.”— Robert Meyer, a professor of marketing at the University of Pennsylvania in response to Superstorm Sandy [4]

Our charge this semester is to develop an architecture that remembers the past, while confidently and creatively attending to the future. The studio will pursue this goal through the design of a single structure, located along Galveston’s most historically precarious site: the Gulf Coast seawall. The structure, a hotel that caters to eco-tourists, will seek to mediate the extreme environmental circumstances that define Galveston today, while searching for an architecture of efficiency, adaptability, and resilience. For studio designers, this means developing a form that

weathers the increasingly severe storms that roll in from the Gulf,

redefines the program, function, and image of twenty-first century tourism,

achieves a powerful and refined architectural expression using limited material resources,

redefines the program, function, and image of twenty-first century leisure,

and makes residents feel safe.

In order to accomplish these ambitious goals, we will utilize a systemic approach to design to emphasizes the interdependence of parts, while continually questioning the boundaries of our work. We will simultaneously subscribe to the following systemic principles of resilient design [5]:

resilient systems transcend scales

resilient systems provide for fundamental human needs

resilient systems are diverse and redundant

resilient systems are simple, passive, and flexible

resilient systems are durable

resilient systems are local, renewable, and reclaimed

resilient systems anticipate interruptions

resilient systems learn from and leverage existing natural systems

resilient systems consider social equity and community

resilient systems are never absolute

Re-examining the Relationship between Form and Sustainability. As the studio aims to balance the complex ecologies of Galveston, it also aims to clarify the complex and often misunderstood relationship between architectural form and sustainability. Specifically, we will pursue the topic of sustainability as a form generator, not a technical overlay. To accomplish this goal, we will model our design process on a highly structured feedback loop that takes into account issues of design and analysis, form and performance. We will always pursue these critical topics in parallel; never in isolation. This means that initial formal impulses must answer to feedback from simulation and software.

A similar dialogue will take place between the two studio instructors, with Professor Rashed-Ali advocating for performance and sustainability and Professor Caine emphasizing architectural and site issues. In the end, the instructors and issues will inform each other, while the responsibility for final design decisions will rest solely with the students. This robust dialogue will commence with initial sketches and continue until final renderings and models are complete.

Ultimately, all proposals must account for the fact that the built environment is a key contributor to a host of environmental pollutants, including the carbon emissions associated with global warming. This studio therefore requires designers to minimize the environmental impact associated with their building and site proposals. This will require each student to simultaneously attend to multiple aspects of site and building design including water use, energy use, resource consumption, occupant comfort and daylighting. At the conclusion of the semester, students must deliver a proposal that is formally dynamic, environmentally efficient, programmatically compelling and that engages users at the scale of the site and building.

Modeling Performance. Dr. Rashed-Ali will introduce student designers to critical software packages, allowing them to leverage the latest technology to model building performance. The studio will focus on the following software packages extensively:

Climate Consultant: Developed by the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA), Climate Consultant enables users to understand, analyze, and visualize local climatic characteristics (i.e. temperature, relative humidity, solar insolation, wind patterns, sky cover) before selecting climate-responsive design strategies.

Sefeira: This software allows users to analyze design proposals, specifically with regard to energy and daylighting performance. It also enables users identify design characteristics that optimize energy and daylighting performance.

Athena Impact Estimator: The software allows students to evaluate the impact of design and materials on the environment (i.e. global warming potential, acidification potential).

AIA COTE Top Ten Competition for Students. “The American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment (AIA COTE), in partnership with the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), is pleased to announce the fourth annual AIA COTE Top Ten for Students, offered this year in collaboration with Architecture 2030 as INNOVATION 2030. The program challenges students, working individually or in teams, to submit projects that use a thoroughly integrated approach to architecture, natural systems, and technology to provide architectural solutions that protect and enhance the environment. The competition will recognize ten exceptional studio projects that seamlessly integrate adaptive, resilient, and strategies for moving towards carbon-neutral operation within their broader design concepts [8].”

[2] The Resilient Design Institute. www.resilientdesign.org/.

[3] Tom Dart, The Guardian, “Glen Campbell’s Galveston: politics of nostalgia echo amid faded grandeur,” 12 August 2017.

[4] The Resilient Design Institute. www.resilientdesign.org/.

[5] The Resilient Design Institute. www.resilientdesign.org/.

[8] AIA COTE Top Ten for Students: Innovation 2030. AIA Committee on the Environment Student Design Competition 2017-2018.

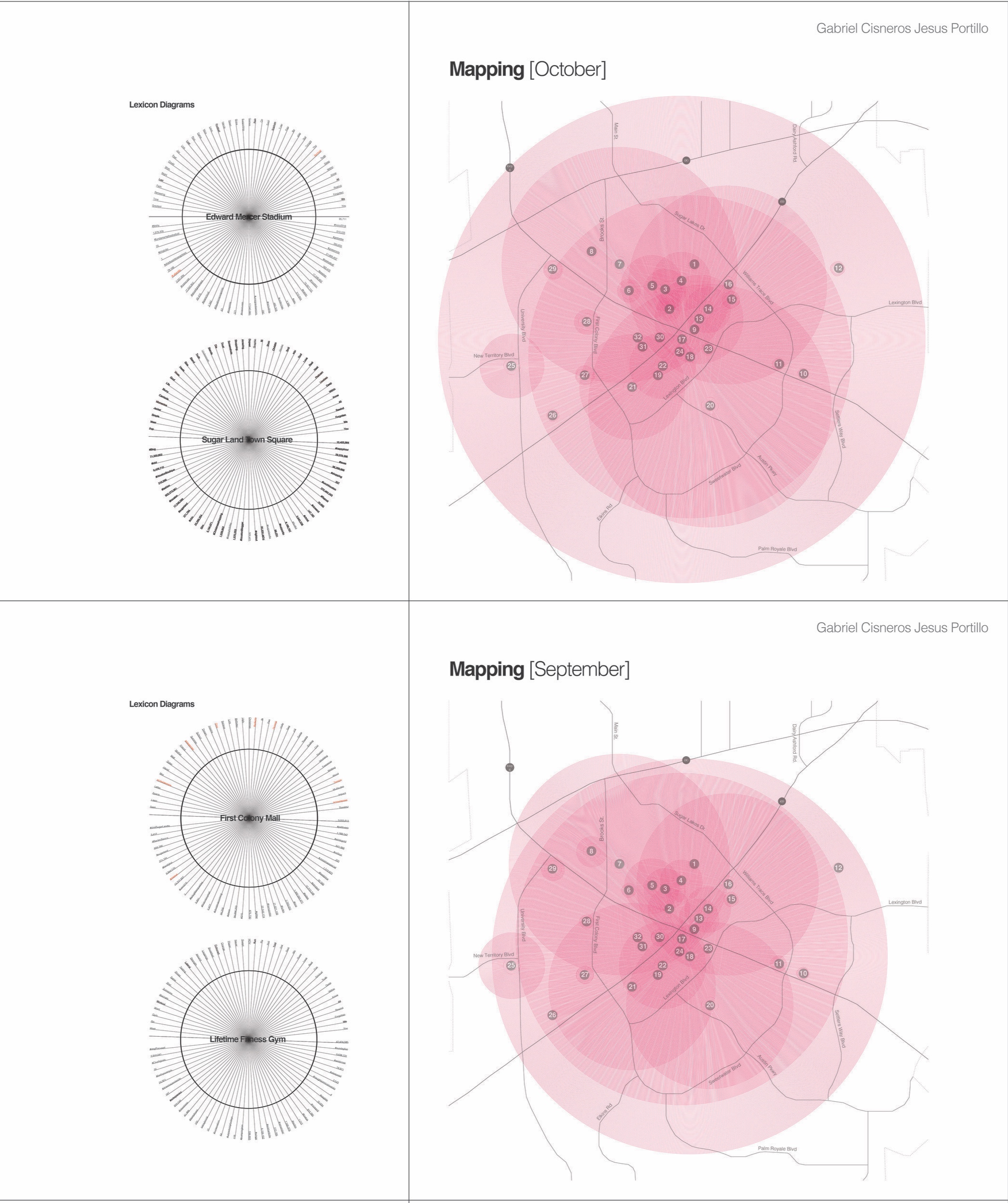

Theorizing Sprawl II

University: UTSA

Type: Seminar

Level: Undergraduate and Graduate

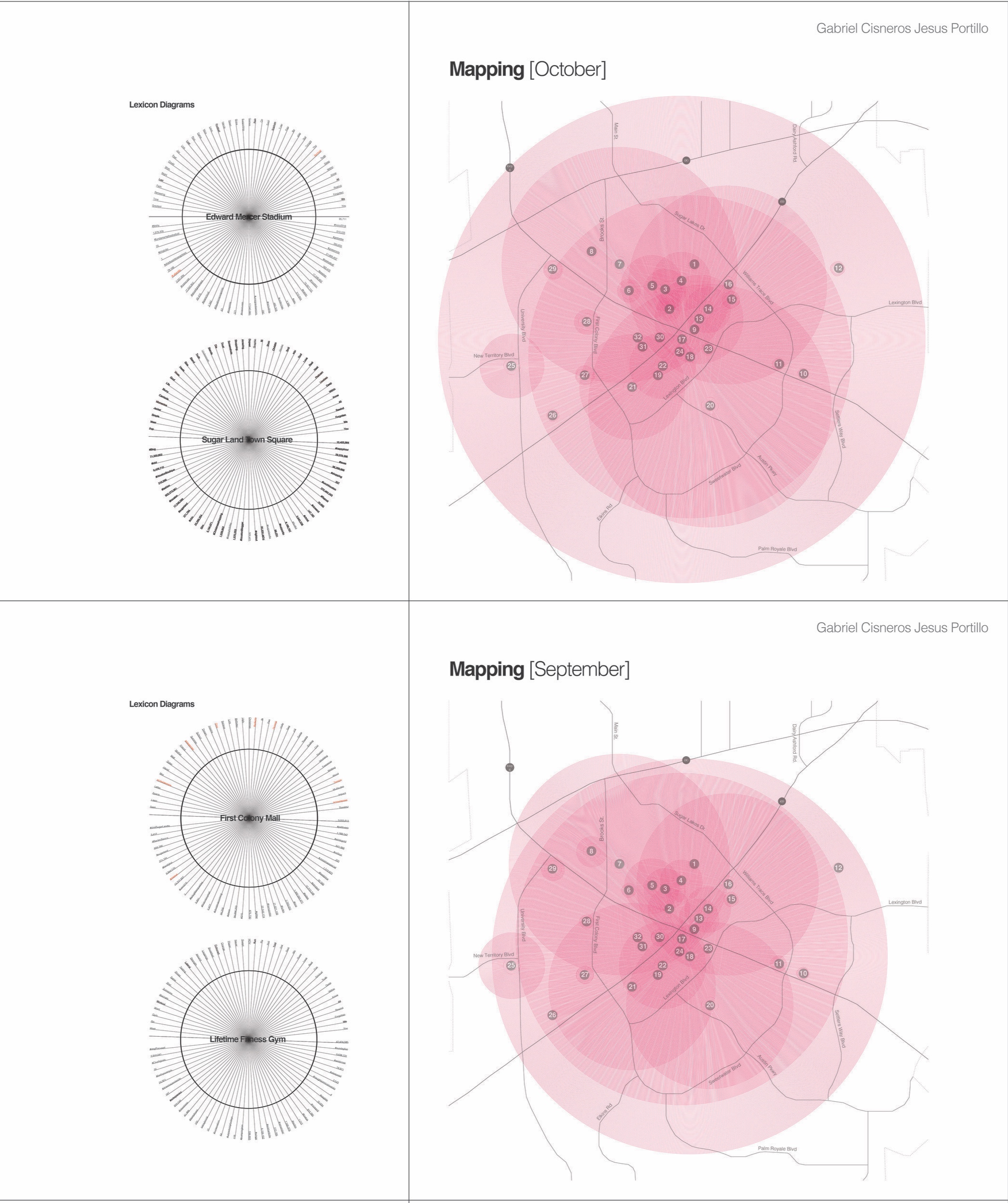

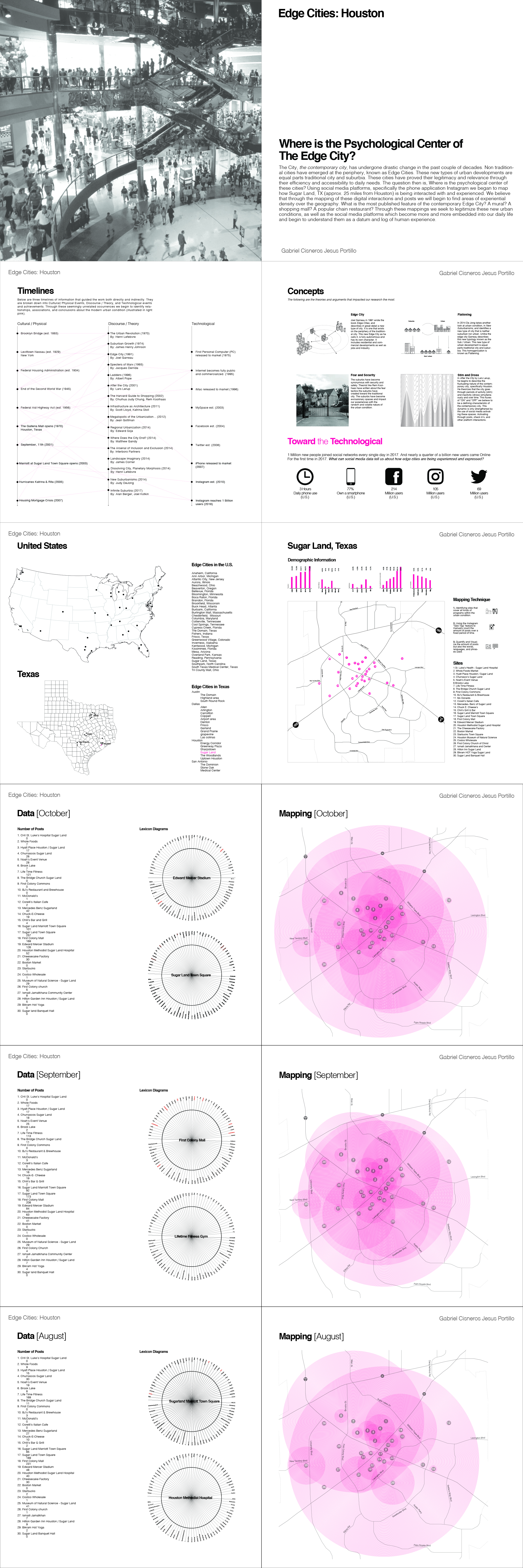

Student Projects: Gabriel Cisneros and Jesus Portillo

Summary

Sprawl is perhaps the most objectionable term in today’s urban lexicon. A wide range of urban actors including policy-makers, planners, public health officials, and designers routinely blame sprawl for the most intractable urban problems. The prevailing sprawl narrative explains that a range of urban challenges from pollution to poor health, cultural dislocation to commute times, will be solved with a return to the compact city. Is this diagnosis accurate? Are we correct to attribute such a wide array of liabilities to a phenomenon as specific as sprawl? If the answer is yes, is it even possible to reverse the prevailing trend towards urban decentralization? This seminar will re-position the sprawl narrative within an accurate theoretical and historical framework. In doing so, the class will pursue answers to the following fundamental questions: What is the most useful working definition of sprawl? Are sprawl and suburbanization the same? When, where, and how has sprawl evolved? What are the verifiable health and environmental impacts of sprawl? What are the competing theories and evaluations of sprawl?

The advanced graduate seminar asks students to undertake one semester-long graphic-based/applied research project within the most critical emerging mega-region in North America: the Texas Triangle (Dallas, Houston, San Antonio). The seminar is structured around the following themes:

Week 01 Definitions

Week 02 Polemics

Week 03 Mapping

Week 04 Form

Week 05 Aesthetics

Week 06 Culture

Week 07 Security

Week 08 Ecology

Week 09 Infrastructure

Week 10 Equity

Week 11 Health

Week 12 Edge

Week 13 Boundary

Week 14 Region

Sprawl Through the Lens of the Spatial Humanities