Toward a New Narrative for the Automotive Strip

Publication: Gregory Marinic and Pablo Meninato (eds.), About Streets: Perspectives on Urbanism, Architecture, and Placemaking (New York: Springer).

Author: Ian Caine

Date: Summer 2025

During the second half of the twentieth century, the automotive strip emerged as an epistemological platform that allowed architects to document, explore, and theorize the increasingly unfamiliar form of the postwar city. Studies like The View from the Road (1964), The Architecture of Four Ecologies (1971), and Learning from Las Vegas (1972) employed radical empiricism to generate new understandings of the automotive landscape and, by extension, the automotive city. The following case study leverages these methodologies while reassessing the past, current, and future impact of automotive technologies on the strip. The case study specifically investigates the historical life of Fredericksburg Road–a heavily traveled arterial in San Antonio, Texas, USA. The research constructs a timeline of Fredericksburg’s growth, registering the strip’s shifting forms, programs, and narratives over 120 years and 12 miles. The exercise establishes five historical eras characterized by the streetcar, automobile, regional shopping mall, edge city, and lifestyle center. In this context, the research considers the transformative potential of more recent trends related to online shopping, shared mobility, and automated vehicles. Collectively, these developments promise to alter the strip's form and program yet again, potentially putting vast amounts of square footage back into play. The chapter concludes by proposing a new narrative for Fredericksburg Road that advocates a smaller, slower, and more local future for the road. By pushing back on a century of modern road design, this alternative narrative resists the technocratic, commodifying interests that developed the automotive strip in their own image.

*****

Today’s San Antonio planners, policy-makers, and designers can push back on 120 years of this technocratic narrative by advocating for a smaller, slower, and more local Fredericksburg Road. A smaller Fredericksburg would prioritize programmatic diversity along the strip, proactively supporting the finely-grained and local programs lost during the twentieth century. This position need not deny or even resist the impact of global capital on the strip; instead, it simply advocates for programmatic balance and economic diversity. A slower Fredericksburg promotes increased mobility, resisting the functional monopoly that automobiles continue to exercise along the strip. In many ways, Complete Streets advocates have already begun this portion of the work–introducing programmatic, scalar, and functional diversity to the famously monolithic road type. This campaign represents a necessary effort to correct a century of damage to the form and function of roads. Finally, a more local Fredericksburg resists cultural homogenization, which in San Antonio means countering centuries of institutionalized racism that pushed Latino populations to the economic margins. Eventually, a better narrative for Fredericksburg must transcend issues of road design, actively questioning the technocratic, commodifying forces that built the automotive strip in their own image.

The Fredericksburg Road case study reveals multiple instances where this narrative is already gaining traction. Small, slow, and local culture is thriving in the undersized lots and buildings that line former streetcar routes, the bustling strip malls of the Deco District, and the flea markets of Wonderland. These examples may be modest, but new technologies promise to unleash significant opportunities to expand similar scenarios. The advent of online shopping and the work-from-home culture continues to threaten retail and office programs with obsolescence, which could prime untold thousands of acres for redevelopment. Likewise, as the functional logic of shared mobility and automated vehicles infiltrates the morphology of the strip, parking lots may recede or disappear–the latest vestiges of yet another transportation revolution. Proponents of the compact city optimistically project that the latter trend will re-centralize and re-densify the city, as we find a higher and better use for the over-built and increasingly unnecessary parking lots. Others suggest that the large-scale adoption of individually-operated automated vehicles will make driving easier, accelerating horizontal expansion and increasing the overall demand for parking.[1]

The outcome of both trends remains to be seen. Still, architects and planners must prepare to embrace what could become a rare opportunity to reprogram, redesign, and reimagine the automotive strip. Whether roads like Fredericksburg can ever command the cultural authority that traditional streets have enjoyed for millennia remains to be seen. However, this uncertainty only reinforces the need to write a new narrative for the automotive strip that aligns with the real people whose lives unfold along the road every day.

*****

Notes

[1] Dominic Stead and Bhavana Vaddadi. "Automated vehicles and how they may affect urban form: A review of recent scenario studies." Cities 92 (2019): 126.

Image: Springer Nature

Undersized buildings along the former streetcar route continue to sustain local businesses well. Image: Ian Caine

Despite faded signs and dated décor, Wonderland of the Americas hosts critical community programs like medical and dental care. Image: Ian Caine

Èilan, a Tuscan-themed lifestyle center at the city’s edge, offers urban elements like streets and plazas but no connection to the road. Image: Ian Caine

Synthetic Utopias for a Post-Katrina Era

Publication: Derek Hoeferlin, Way Beyond Bigness: The Need for a Watershed Architecture (AR+D Publishers)

Author: Ian Caine

Date: Summer 2023

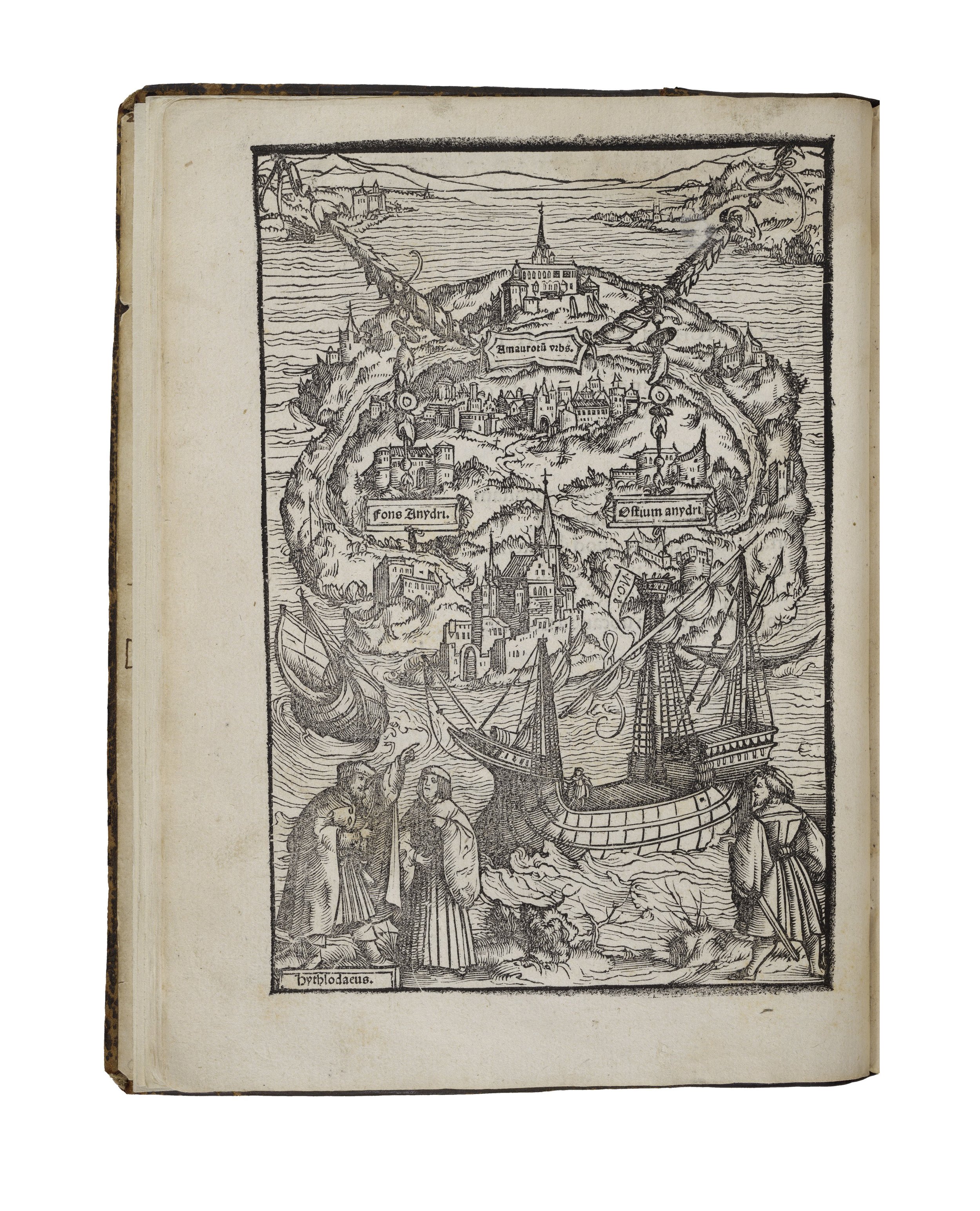

In Thomas More’s 1516 novel Utopia, King Utopos initiates the pursuit of architectural utopia with a grand act of separation. He uses water to do it, severing a 15-mile-long isthmus to construct an artificial island called Utopia. By breaking all physical or historical connections to the mainland, the fictional island of Utopia emerges as a powerful metaphor, reminding us that the fundamental impulse of architectural speculation has long been to escape the obligations of physical and political context. If the origins of architectural utopia reside in the power of water to separate, however, in the post-Katrina era water is reemerging as a synthesizing force, prompting urbanists to align their formal speculations with prevailing ecological and sociopolitical realities. Today, the opportunities and constraints associated with water are prompting architects, landscape architects, and urban designers to dramatically recast the parameters of urban speculation, challenging the veracity of the autonomous project in architecture while recovering the best utopian impulses of the Modern project. Within this context, Derek Hoeferlin positions his broad portfolio of work—presented here as Watershed Architecture—as a fully synthetic project, one that aligns urban speculations with the multiple logics of water at the metropolitan, regional, and continental scales.

*****

As designers, we crave constraint. Tight budgets and boundaries often inspire our best work. Given the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina, and more recently Gustav, Ike, Sandy, Maria, and Harvey, the existential threats associated with water are emerging as the ultimate check on our urban imaginations: while water’s most tangible limits are ecological and technical, we are learning—belatedly—that the limits are social and political too. The argument that Derek Hoeferlin presents in Way Beyond Bigness is fundamentally a response to the severe ecological and sociopolitical limits of water. The multiscalar, multidisciplinary approach aligns with that of leading practitioners in architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design. Collectively, these practices are leveraging water’s inherent ecological and sociopolitical constraints to reengage the utopian trajectories that most abandoned in the latter stages of the Modern project. This period saw Modern architecture surrender its foundational social agenda while diverting attention to issues of postmodern allusion or autonomous formalism. Such detours have pushed architects to the periphery of urban discourse, allowing real estate developers and media to fill the vacuum.26 This retreat has rendered our discipline incapable of addressing existential environmental threats during the post-Katrina era.

With Way Beyond Bigness, Hoeferlin seeks to counter these trends by rehabilitating the Modern project’s unfulfilled social agenda. Taken as a whole, the ideas presented in this book contribute to a broader, emerging urban project that begins with the postmodern attention to context, forged by figures like Colin Rowe and Reyner Banham; scales up to meet the regionalist aspirations of Patrick Geddes and Lewis Mumford; leverages the commitment to systems and ecology prescribed by Ian McHarg and James Corner; and embraces the ethical imperatives of environmental justice movements like #NoDAPL, the grassroots campaign to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline. Collectively, this deep and diverse intellectual lineage is supercharging our understanding of context and providing the terms for speculative, transcalar, and transdisciplinary projects like Watershed Architecture.

*****

Watershed Architecture finally submits that the future of urban speculation is not about building bigger or better islands; it is not about discovering New Worlds, here on earth or beyond. Instead, it offers that the next utopia will emerge from an expanded definition of context and a more sympathetic alignment between cities, water, and people. That alone is a radical speculation, one sufficient to inspire grand visions of urban futures and a new measure of what it means to think big.

Images: AR+D Publishing, The Folger Shakespeare Library, U.S. National Archives

TEXAS UNBOUND

Publication: MONU 26: Decentralised Urbanism

Author: Ian Caine

Date: Summer 2017

The drive across Texas is a glorious adventure, rewarding travelers with a dazzling array of forests, cities, mountains and deserts. The 812-mile excursion is also grueling, consuming no less than 12 hours and two full tanks of gas. The road trip itself is a powerful experience, one that compels travelers to submit to the unbound character of the landscape. Infinity is an existential quality in Texas. It radiates from the long sky, illuminating the region’s politics and people.

Texas Unbound proposes a similar surrender, to the decentralized condition that defines urbanism in the Texas Triangle. This rapidly expanding megaregion—anchored by Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth and San Antonio--contains five of the United States’ ten fastest growing large cities [1]. In 2009, the Texas Triangle was home to 15 million people, covered 60,000 square miles, and expected another 10 million residents over the next 45 years [2]. The region’s staggering growth is the result of massive oil and gas extraction, continuous immigration from Mexico and the U.S., business-friendly regulations and reliably low housing prices.

The vast majority of the 66 counties that comprise the Texas Triangle maintain population densities below 400 people per square mile, while metropolitan areas rarely exceed 3,500 people per square mile [3,4]. To put this in perspective, the population density in Los Angeles is 10,806 people per square mile, or about three times that of a typical city in the Texas Triangle [5]. Universally low density, coupled with a populace that is dispersed among five major metropolitan areas, make decentralization the baseline urban condition in the Texas Triangle. In order to build a relevant theoretical framework in this context, one must enjoin a lineage that embraces the nodal structure of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City; the cumulative growth of Patrick Geddes’ conurbations and Jean Gottmann’s Megalopolis; the spatial diffusion of Wright’s Broadacre City; and ultimately, Henri Lefebvre’s theory of complete urbanization, which obliterates the classical distinctions between city, suburb, and countryside [6]. This sweeping intellectual trajectory ends with the conceptual dissolution of the city as a bound metropolitan unit. In its place a polycentric, diffuse urban structure emerges that answers to a variety of names including urban conurbation, megalopolis, and megaregion. The following eight vignettes seek to capture the unbound characterof the Texas Triangle in words and images, generating new insights into the conditions of decentralized urbanism in the region.

The center is no longer the center. Main Plaza, San Antonio, Texas.

The edge is no longer the edge. Uptown, Houston, Texas.

Anachronism is the new history. John T. Floore Country Store, Helotes, Texas.

History (still) matters. Misión San Antonio de Valero, San Antonio, Texas.

Private is the new public. State Highway 30/Future Bullet Train Station, Brazos County, Texas.

Cars are (still) the future. US Highway 75 at I-635, Dallas, Texas.

Bigger is (still) better. San Marcos Outlet Malls, San Marcos, Texas.

Hybrid is the new mixed-use. Fuel-City, Dallas, Texas.

Decentralization is the new normal. The Texas Triangle Megaregion.

*****

Anachronism is the new history. John T. Floore Country Store, Helotes, Texas. In Texas, geographic displacement begets chronological displacement. For proof, look no further than Helotes, Texas (population 8,104), where it appears that the historical shelf life of a city may be about to expire. Helotes is perhaps best known as home of John T. Floore Country Store, the city’s iconic honky-tonk that opened in 1942 and quickly made its legend hosting musical greats like Elvis Presley, Patsy Kline, and Hank Williams. Three-quarters of a century later, country music devotees continue to pack the venue’s long, wooden family-style tables for some of the hottest tamales and coldest beer in South Texas. On a good night, they’ll catch a set from the immortal country crooner Willie Nelson.

Recently John T. Floore’s has become harder to find, its perch in Helotes bypassed years ago by a divided arterial roadway. Decades of leap-frogging sprawl from expanding neighbor San Antonio now engulf the Helotes honky-tonk, which finds itself awash in gated subdivisions, rising property taxes, and familiar big box offerings from Target, Lowe’s, and Home Depot.

It’s towns like Helotes that bring the confounding challenges of decentralized urbanism into sharp relief. As cultural phenomena go, Helotes is an enigma wrapped in a riddle: the town that began as a roadside layover for stagecoach travelers is now a tony suburb of San Antonio, one of the ten fastest growing cities in the United States. Still, in 2013 Bloomberg Businessweek named Helotes as one of the fifty best places to raise kids in the U.S., citing the great schools, small-town charm, and a median household income north of $100k. The rapid transformation has become difficult for locals to swallow--not surprising in a town that was once the stomping grounds of Willie Nelson and his band of country Outlaws. So it is that Helotes’ legacy and San Antonio’s aspiration endure an uneasy standoff, each hoping that their complex history doesn’t devolve into anachronism.

*****

Notes

[1] United States Census Bureau. "The 15 Cities with the Largest Numeric Increase between July 1, 2014, and July 1, 2015, with Populations of 50,000 or More on July 1, 2014."

[2] Kent Butler, Sara Hammerschmidt, Frederick Steiner, Ming Zhang. "Reinventing the Texas Triangle: Solutions for Growing Challenges." 14, 2009.

[3] U.S. Census Bureau. “Texas Population per Square Mile, 2010 by County.” http://www.census.gov/geo/www/tiger/index.html or http://factfinder2.census.gov.

[4] Zip Atlas. “Cities with the Highest Population Density in Texas.” http://zipatlas.com/us/tx/city-comparison/population-density.htm.

[5] Zip Atlas. “Cities with the Highest Population Density in California.” http://zipatlas.com/us/ca/city-comparison/population-density.htm.

[6] Henri Lefebvre. "From the City to Urban Society." In Implosions/Explosions: Toward a Study of Planetary Urbanism, edited by Neil Brenner, 36-38. Berlin: Jovis, 2014.

Images: Michael Wolf/BOARD Publishers (cover), BOARD Publishers (video), Chase White, Chase White, Chase White, Ian Caine, Ian Caine

INFRASTRUCTURE AND ILLUSION IN THE AGE OF TRUMP

Publication: Log 39

Author: Ian Caine

Date: Winter 2017

excerpt:

I would build a great wall, and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me…

– Donald Trump on announcing his candidacy for President of the United States, June 16, 2015.

When Donald Trump stepped up to the podium at Trump Tower to deliver these now infamous words, most observers dismissed his infrastructural vision as the fevered dream of an aging real estate mogul and reality television star. Twenty unimaginable months later, as President Trump leads a stunned nation forward, it’s worth taking a moment to dispel any notion that his administration intends to leverage civil infrastructure for civic good.

At a height of up to 50 feet and a total length of almost 2,000 miles, Trump’s great wall at best embodies grand political theater that is woefully out of touch with the real politics and landscapes of the US border region. For proof, look no further than the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, where you might excuse residents who feel like they’ve seen this drama play out before. That’s because the State of Texas ran a similar production titled the Trans-Texas Corridor (TTC) between the years 2001 and 2010. If you missed that one, the plot reads like a 1950’s horror flick: a slithering asphalt superhighway cuts a 1,200-foot-wide swath of land between the maquiladoras of Northern Mexico and the malls of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex, shuttling freight and utilities to US consumers while swallowing up all the ranches and farms in its path.

At the time, the TTC was the pet project of then Governor Rick Perry, Trump’s 2016 Republican rival whom the new president summarily trounced, then picked up, brushed off, and installed as Energy Secretary. Note that historically, Governor Perry demonstrated far more affection for the TTC than he did for the Department of Energy, an outfit he famously forgot about when asked in a public debate to explain why he wanted to eliminate it.

As Texas-sized boondoggles go, Trump’s great wall and Perry’s superhighway share a lot in common: Trump’s great wall adds 1,000 miles to the already fortified southern US border and will cost up to $25 billion to complete. Perry’s superhighway would have covered 4,000 total miles and cost at least $185 billion. Trump’s great wall faces intense construction challenges and widespread political opposition from residents of the Rio Grande Valley, where most counties broke strongly for Hillary Clinton in 2016. Perry’s superhighway was similarly unbuildable, facing not only technical challenges but a resounding chorus of boos from environmentalists, property rights advocates, government watchdogs, and conspiracy theorists alike.

While the projects are parallel in scale, they are perpendicular in geography and intent: Trump’s great wall runs east-west. Perry’s superhighway ran largely north-south. Trump’s great wall is a shameless play to nationalism. Perry’s superhighway was a massive giveaway to multinational capitalism. Trump’s great wall aspires to divide nations. Perry’s superhighway sought to unite them. In this last regard, Perry’s fever dream was perhaps more optimistic than Trump’s, at least at the margins. Still, these two men are cut from the same cloth, and the grand infrastructural projects that they champion rate equally bankrupt as civic propositions.

Sadly, if either the great wall or the superhighway were ever completed, the most significant accomplishment would be to consolidate the only stable elements of Trump’s otherwise vacillating personality – that is, a calculating xenophobia and ethically rudderless affinity for corporate profits. Neither quality should give urbanists much optimism for the immediate future of the Republic, in either Texas or the United States.

-Ian Caine, January 2017

Images: Anyone Corporation (cover), U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Michael Vadon, Texas Transportation Commission via Associated Press

THE CONTINENTAL COMPACT: EASTWARD MIGRATION IN A (NEW) NEW WORLD

Publication: Scenario 6 Migration (U of Pennsylvania School of Design)

Designers: Ian Caine, Derek Hoeferlin

Team: Emily Chen, Tiffin Thompson, Pablo Chavez

Date: 2018

Full Article: https://scenariojournal.com/article/the-continental-compact/

00: Introduction

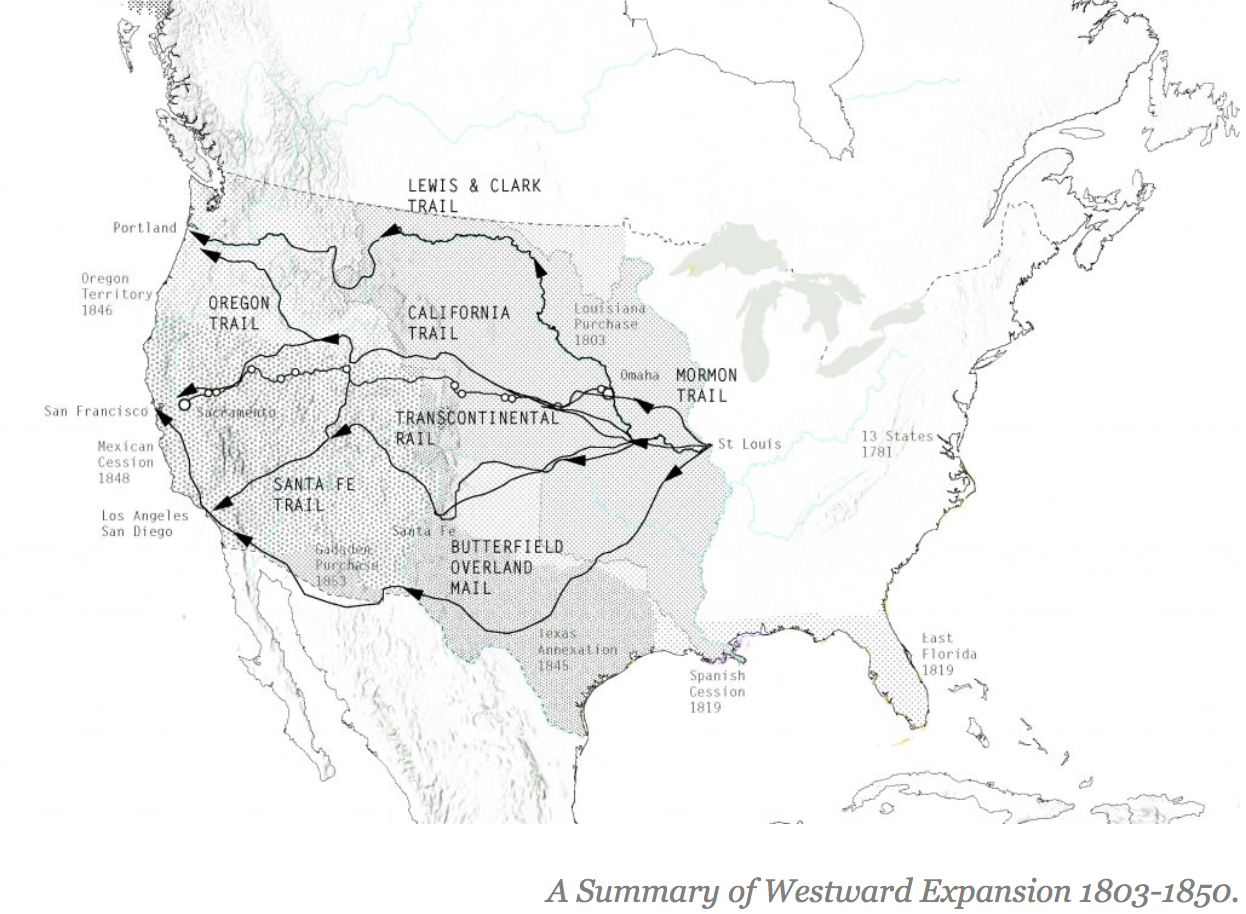

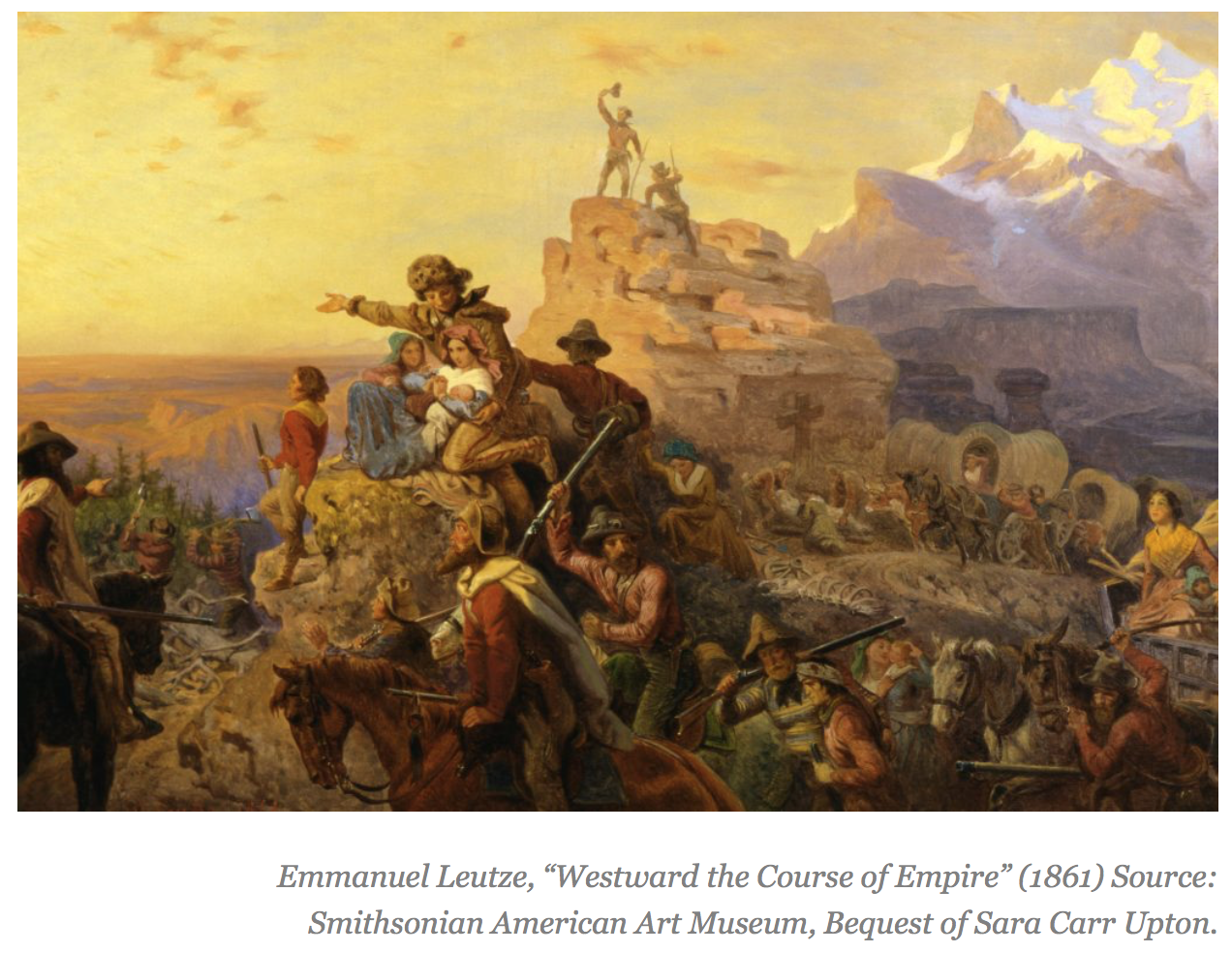

The geographic and cultural history of the United States is largely a chronicle of transcontinental migration and westward expansion. The epic story, both celebrated for its heroic conquests and decried for it devastating social and environmental impacts, comprises a number of well-known chapters including The Louisiana Purchase (1803), Lewis and Clark’s subsequent exploration of the territories (1804-06), The California Gold Rush (1848), The Homestead Act (1862), The Transcontinental Railroad (1863-1869), and more recently the massive tech migration to Silicon Valley (1970s-present) and influx of Mexican nationals to California (1980s-present).

Historian Leo Marx famously contends that the larger narrative of westward expansion was built on three foundational themes, each integral to the American psyche: the first involved the vastness of the physical territory, which was virtually unimaginable to the 19th century European mind; the second encompassed the cultural opposition between the eastern portion of the country, thought to be civilized and constrained, and the west, supposedly raw and untouched; and the third comprised the inclination towards geographic conquest, which was well-steeped in a Protestant ethos that characterized the natural world as lawless and in need of redemption [2].

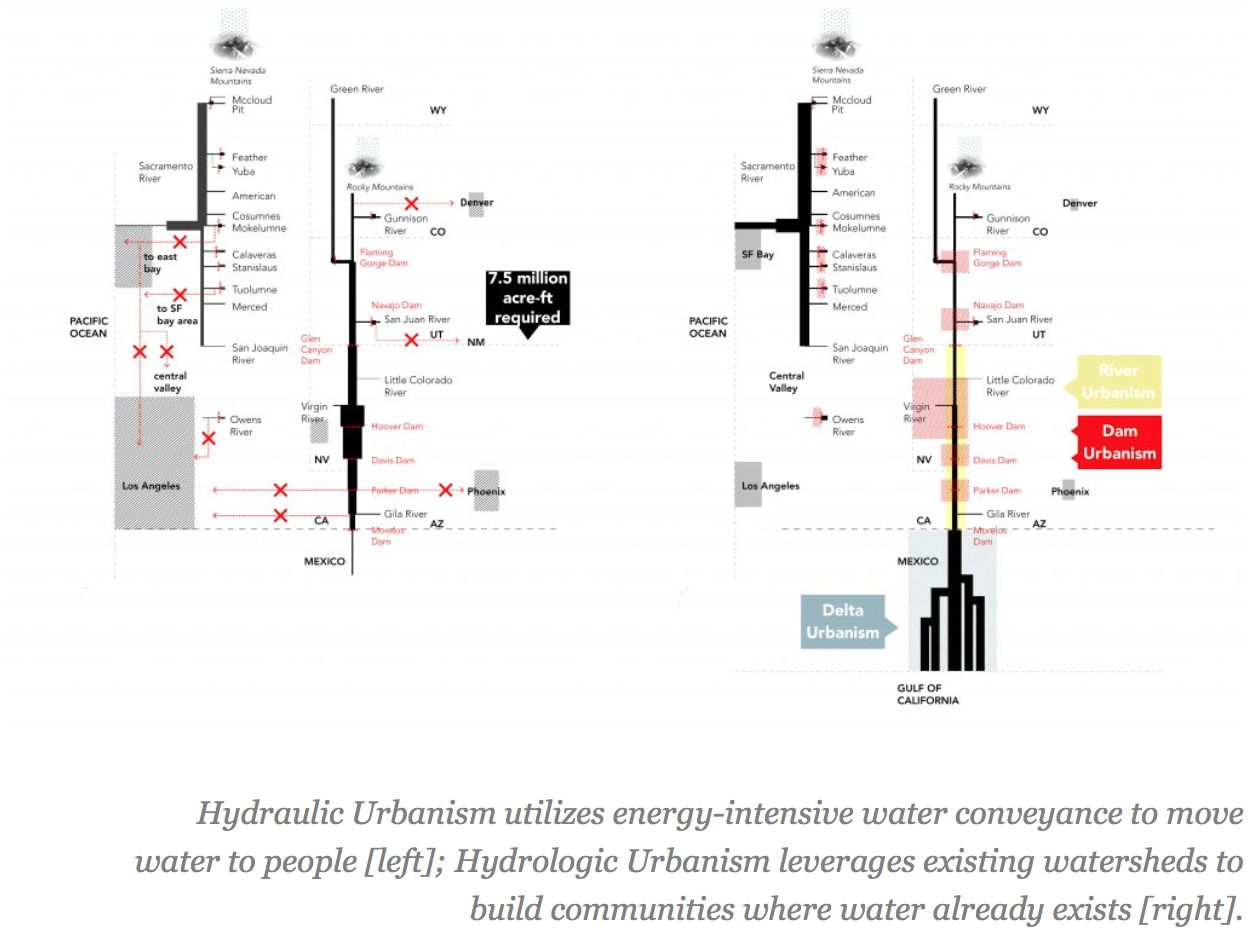

Nowhere has the American disposition towards geographic conquest been more apparent than in the cultivation and maintenance of water resources. Federal dam and water projects in the American West appeared as early as 1877 when the Desert Land Act began gifting land to local farmers who agreed to irrigate their land. The Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 exemplified an early effort to introduce flood control, hydroelectric power, irrigation, water access, and recreation. Between the years 1945 and 1975, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation undertook a dramatic dam-building campaign that impacted virtually every watershed across the American West [3]. This collective history reveals a cultural disposition to harness water resources for financial gain and perceived public good, all while enabling continued westward migration [4].

The Continental Compact proposes a new chapter for the American story, one that continues to leverage water resources for public good, but does so in a more ecologically viable way. In this alternative narrative, Americans make a radical retreat from the mythology of westward expansion, opting instead for a massive reinvestment in regions where water resources remain abundant and underutilized. This premise has very real origins in the current events of the State of California—geographic and spiritual mecca for westward expansion, yet home to recurring droughts that make continued migration virtually impossible. Continued westward migration relies on a continuous campaign of mechanical water conveyance, maintained via a massive, expensive, and ecologically devastating system of aqueducts, canals, pipes, and pumps.

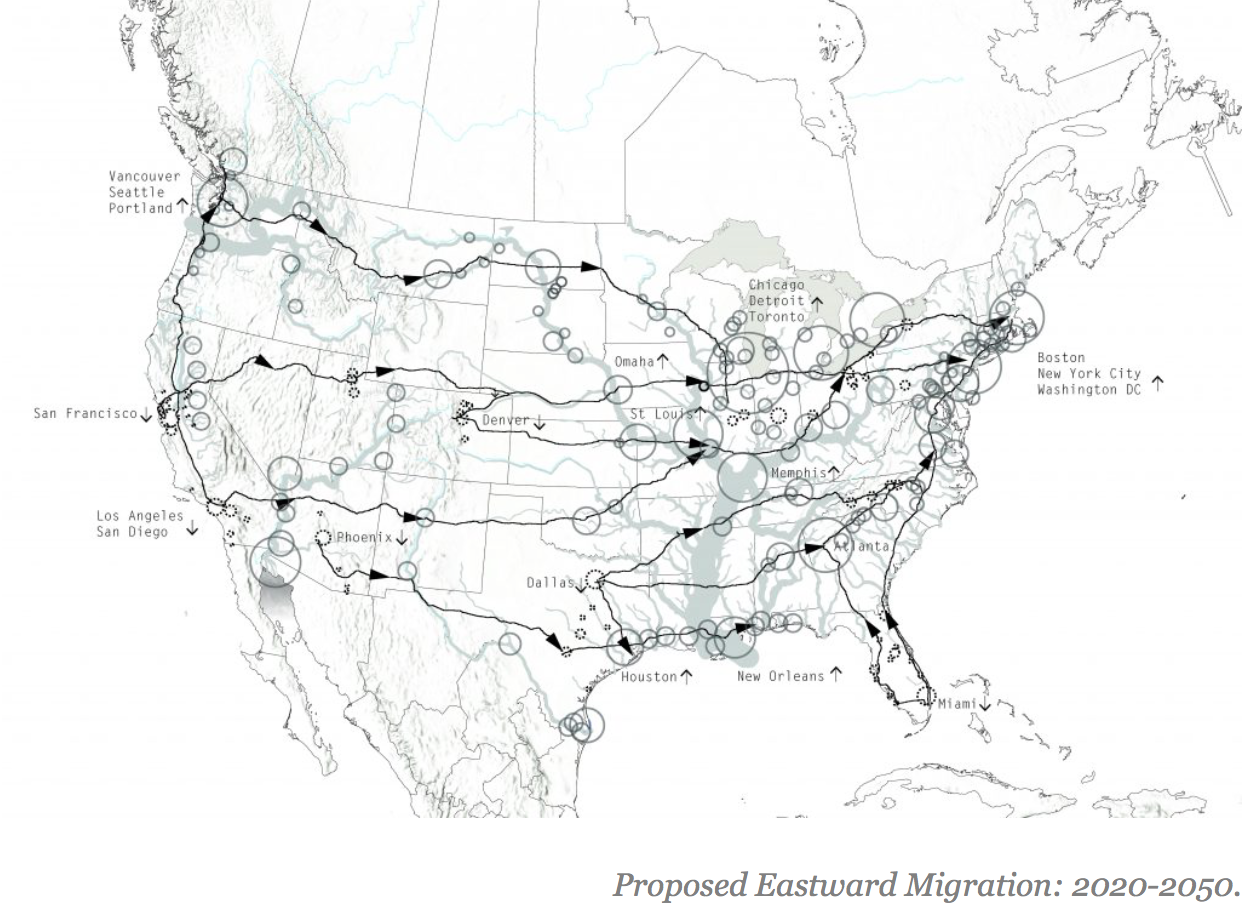

This proposal contends that the next wave of transcontinental migrations will head east, supported by shifting public policies that stop moving water to people and start moving people to water. These transformational policies will forsake a historical desire to exert dominion over natural resources, instead adopting a more pragmatic approach that acknowledges the opportunities and constraints of local watersheds.

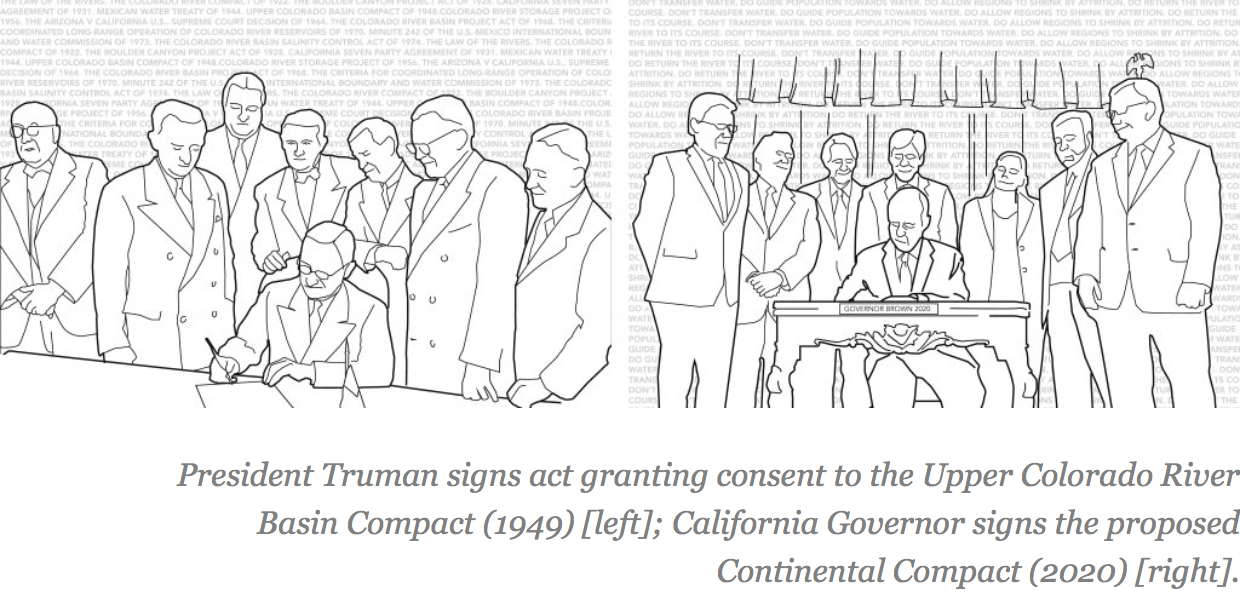

01: The Continental Compact

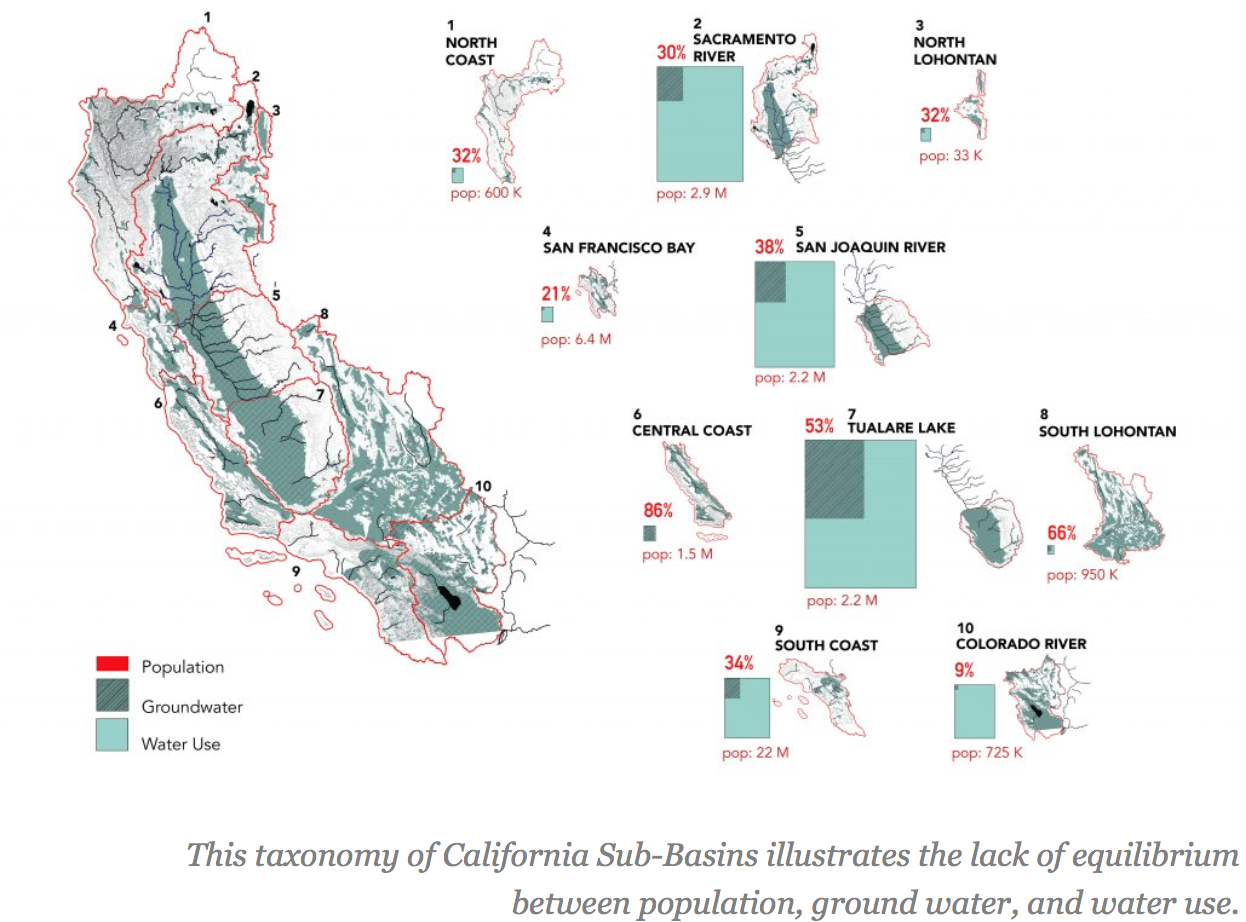

The water crisis in California is first and foremost a political crisis. Decades of public policy have created a massive system of water conveyance, fostering a fundamental misalignment between the supply and demand of water. An elaborate slew of public policies maintain the untenable status quo in California, which supports a system of water-trading between western states.

The Continental Compact sets the stage for a series of new transnational agreements that adhere to three simple principles:

+ Guide population growth towards water.

+ Allow water-starved regions to shrink via attrition.

+ Return the river to its hydrologic course.

*****

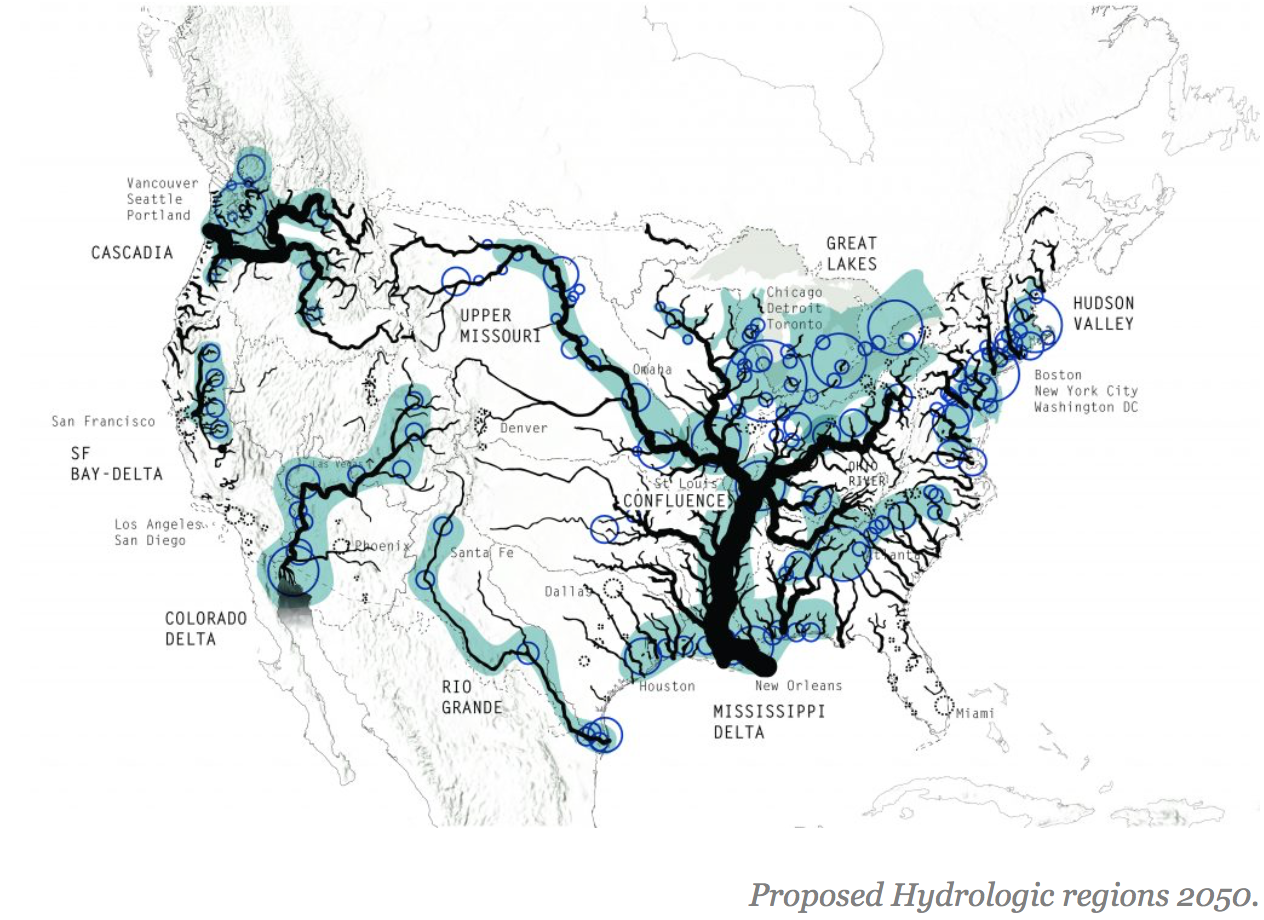

07: From Megaregions to Hydrologic regions

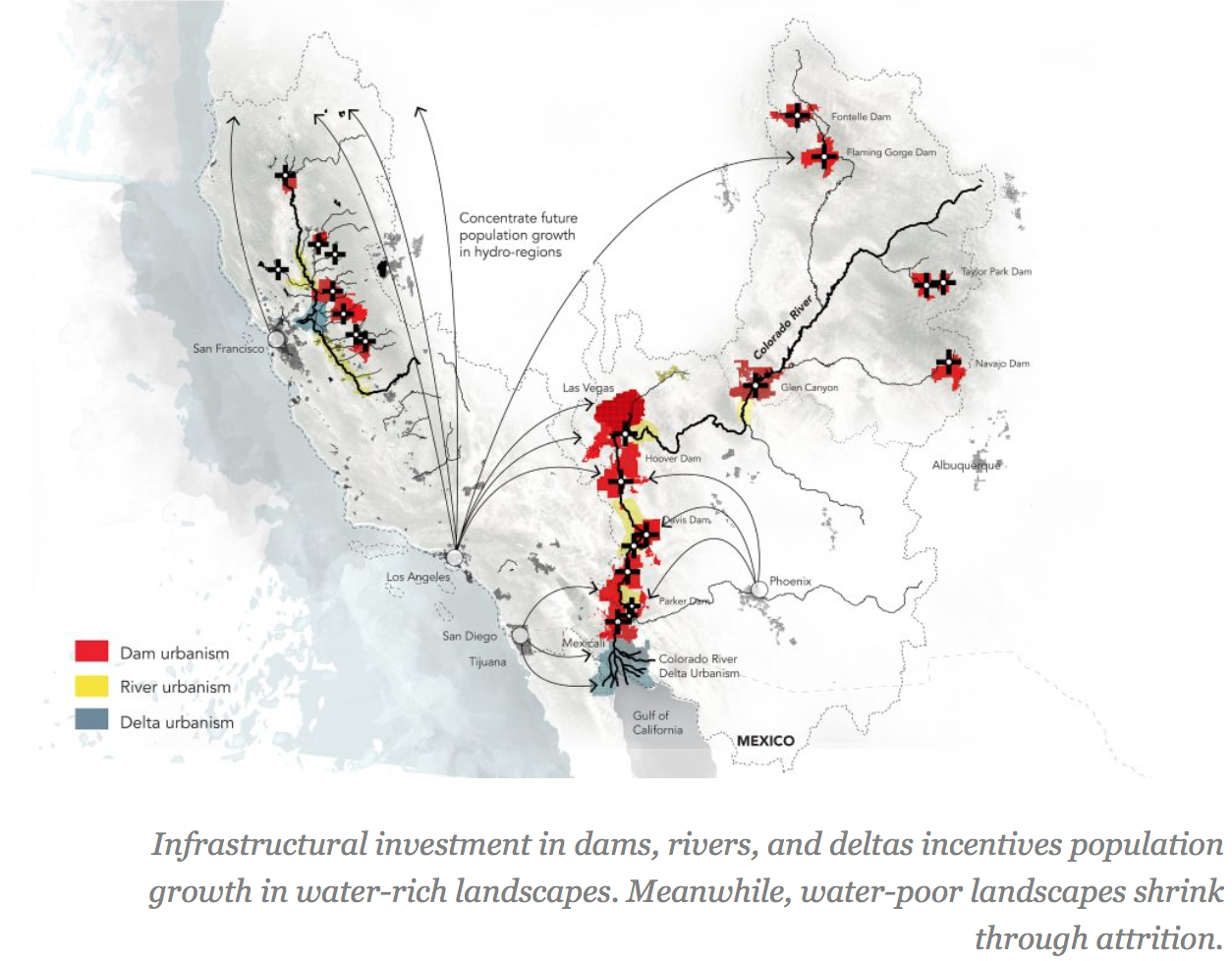

The Regional Planning Association forecasts that urban growth in the United States will produce eleven megaregions by 2050. The Association suggests that six major trends will shape the country’s growth: global trade patterns, demographic expansion, inefficient land use, inequitable growth patterns, global climate change, and aging metropolitan infrastructure. They further recommend that federal policy-makers utilize a megaregional model to guide decisions regarding large-scale infrastructural investments [5]. Remarkably, these growth projections don’t factor what will possibly become the most critical determinant of successful urbanism: water supply.

The Continental Compact recommends that policy-makers begin shifting their focus from megaregions to hydrologic regions, investing in water-rich local urban conurbations built around dams, rivers, and deltas. The Continental Compact re-invests the massive resources that support the existing aqueduct system into the construction and maintenance of new infrastructure in water-rich regions. This strategy reprioritizes ecological sustainability at the continental scale, renouncing our historically antagonistic relationship with local watersheds and topography, transcending national boundaries as required. The result will be a series of eastward migrations, supported by public policies that stop moving water to people and start moving people to water.

*****

Notes

[1] Scenario Journal, “Call for Submissions: SCENARIO 6 Migration,” accessed April 30, 2016, https://scenariojournal.com/call-for-submissions-scenario-6/

[2] Leo Marx, “American Ideology of Space,” in Denatured Visions, ed. Stuart Wrede and William Howard Adams (New York: MoMA 1991) 63-64.

[3] William Wyckoff and William Cronon, How to Read the American West: A Field Guide (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014). 265.

[4] Wyckoff and Cronon, How to Read the American West, 266.

[5] “Megaregions,” America2050, 6, accessed April 1, 2016, http://www.america2050.org/megaregions.html

Images: Scenario Journal, Inc.; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Sara Carr Upton; remaining images by Ian Caine and Derek Hoeferlin

OBSERVATIONS ON THE BIGGEST GAS STATION IN THE WORLD

Publication: Log 35

Author: Ian Caine

Date: Fall 2015

“I wanted to build a facility that was bigger than need be,” explained Arch “Beaver” Aplin III to the Wall Street Journal in 2012. When he opened Buc-ee’s--a South Texas gas station featuring 60 gas pumps, 80 soda fountains, and 33 cash registers--few observers doubted that Aplin, the aspiring architect turned swaggering developer, had just built the biggest gas station in the world.

The location of the crown jewel in Aplin’s growing chain of gas stations was no accident: he cherry-picked the 19-acre parcel for a Texas-sized pit stop along the 79-mile stretch of Interstate 35 that connects Austin and San Antonio, two of the fastest growing cities in the United States. Weary commuters know they’re halfway home when they see the colossal canopy for Buc-ee’s on the horizon, an iconic reminder that an awe-inspiring machine awaits to fuel their tanks and stomachs with a steady stream of gasoline and carbonated beverages.

Meanwhile, voracious developers continue to swallow the remaining land between Austin and San Antonio, where settlers once divided the prairie into farms that home builders are now busy subdividing into culs-de-sac. So it is that these two historically isolated cities have begun traveling the road towards a collective future, one that will pass through the seemingly endless row of self-service lanes at Buc-ee’s, transforming today’s commuters into tomorrow’s citizens of an I-35 megalopolis. Last year, Aplin doubled the number of gas pumps to 120. It’s starting to look like Beaver’s original plan was too modest: the biggest gas station in the world will turn out to be just big enough after all.

-Ian Caine, August 2015

Images: Anyone Corporation (cover), Ian Caine

THE GEOGRAPHIC AND SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC TRANSFORMATION OF MULTIFAMILY HOUSING IN THE TEXAS TRIANGLE

Publication: Housing Studies

Authors: Rebecca Walter, Ian Caine

Date: 2018

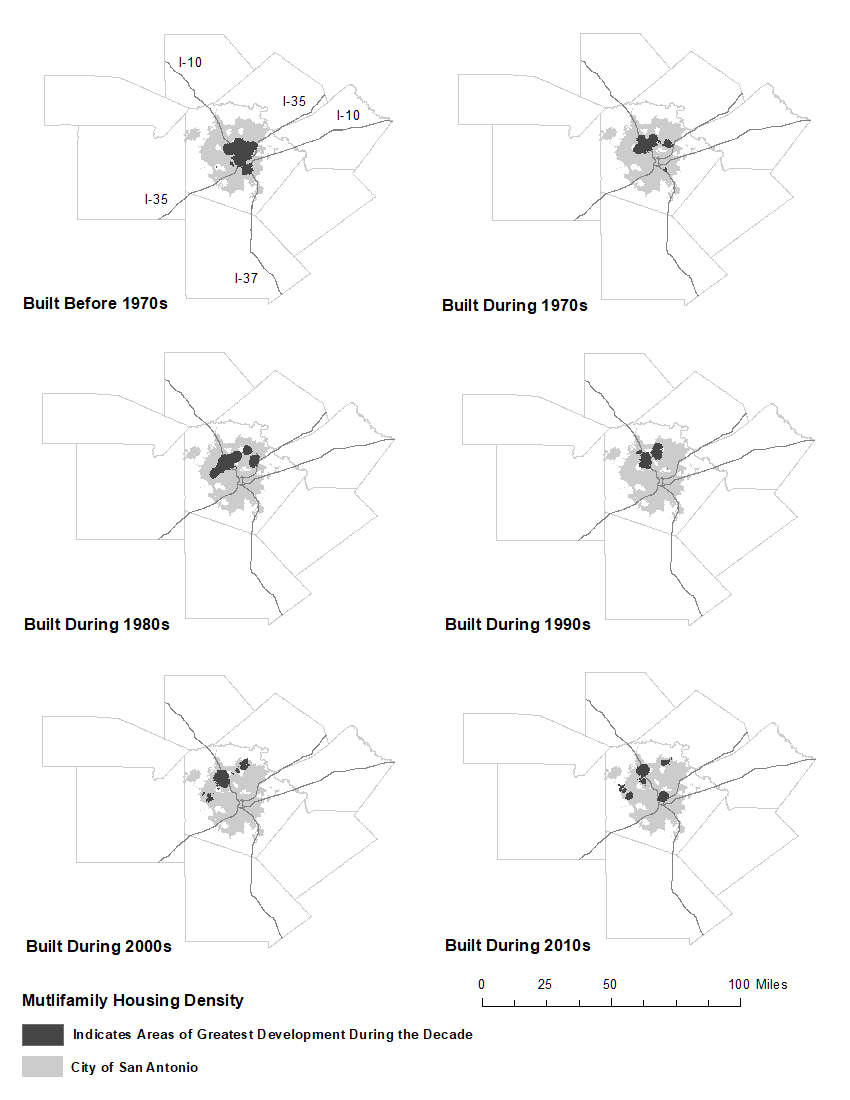

Abstract. This study catalogs the location, clustering, and sociodemographic distribution of the development of multifamily rental housingover the last five decades in the Texas Triangle, one of the fastest growing megaregions in the United States. The research reveals prior to the 1970s, apartments clustered in downtown areas; throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the development of apartments expanded to the suburbs and along major interstates; and in the 2000s, apartment growth continued in the peripheral areas while returning downtown. During this time period, apartments were developedmost often in majority White, high-income, and low-poverty neighborhoods. These geographic and sociodemographic characteristics challenge widespread conceptions that equate multifamily rental housing with central city locations and low-income populations. The findings suggest that multifamily rental housing offers a powerful tool to increase residential density in downtown and suburban locations, while also accommodating a sociodemographic diverse population.

*****

Discussion. The results of this study clearly indicate that the location and clustering of multifamily rental housing development within the four largest MSAs in the Texas Triangle do not correspond to downtown or distressed neighborhoods in inner-city locations. Rather, prior to the 1970s, multifamily housing remained clustered in the downtowns of the largest cities; during the 1980s and 1990s, apartments expanded to the suburbs and along major interstates; and during the 2000s, the development of apartments simultaneously continued an outward growth pattern while returning to the central cities. All MSAs in the study area, with the exception of Austin, experienced a concentration of multifamily rental housing development in majority White, higher-income, lower-poverty neighborhoods regardless of the decade of development. The Austin MSA remained an outlier, as multifamily rental housing development consistently clustered in lower-income, higher-poverty, and minority neighborhoods. The overall findings suggest that multifamily rental housing, despite its historical association with inner-city, higher-poverty neighborhoods, has re-emerged in the Texas Triangle in predominantly middle-income White suburban neighborhoods.

Images: Taylor and Francis (cover), Ian Caine and Rebecca Walter

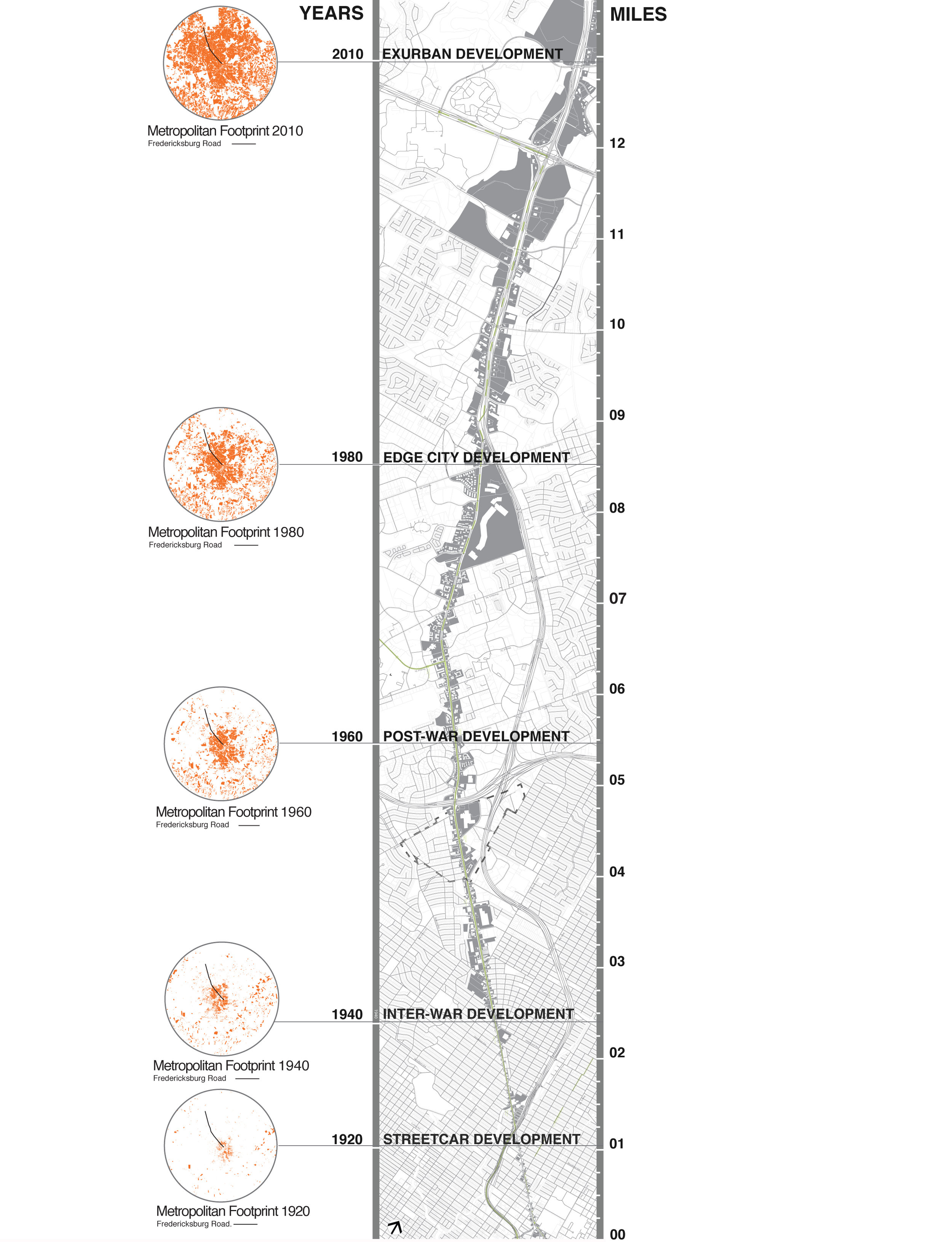

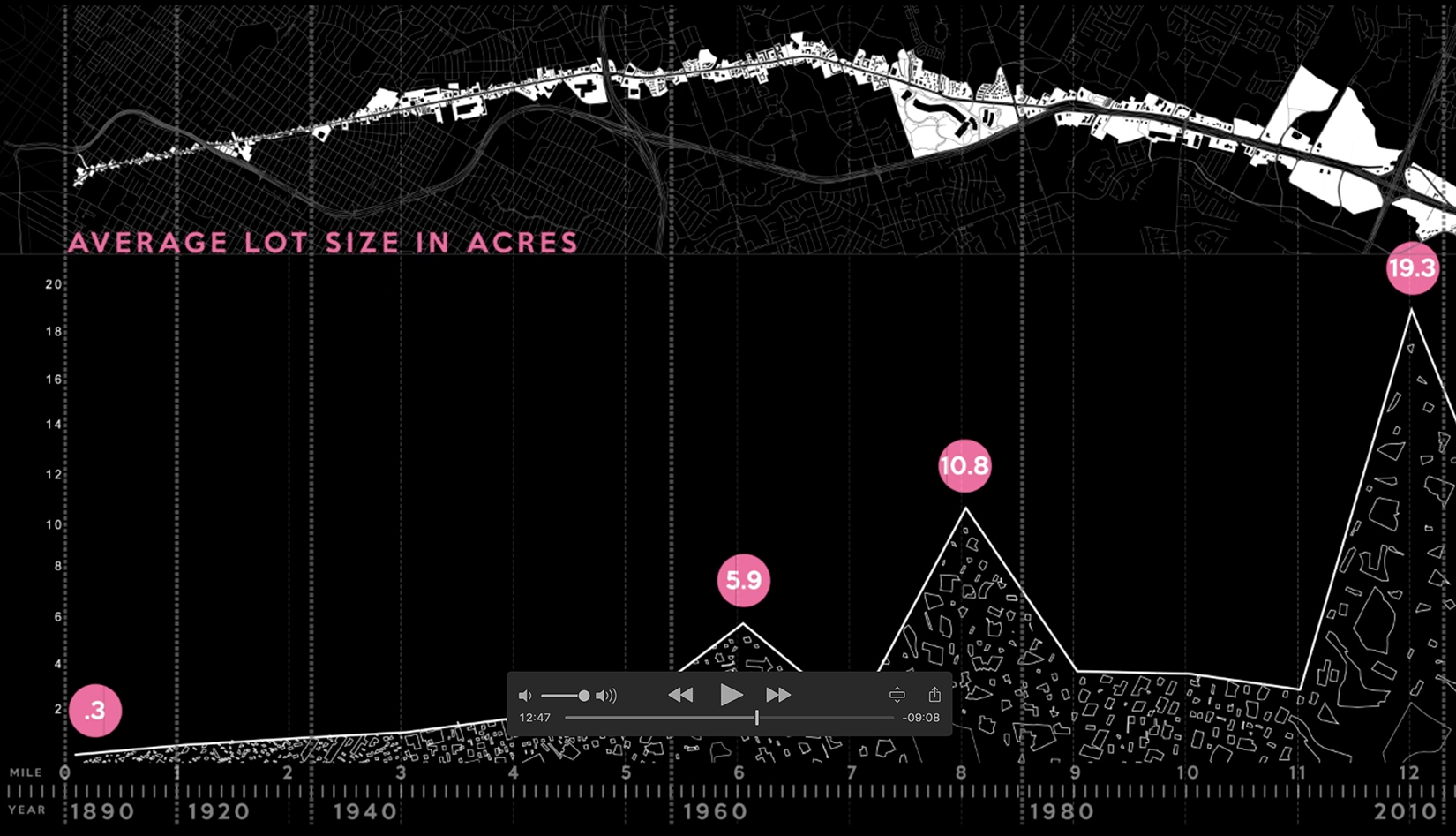

INHABITING THE LINE: A DIGITAL CHRONOLOGY OF SUBURBAN EXPANSION FOR SAN ANTONIO, TEXAS

Publication: International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing (Nicholas Bauch, Guest Editor)

Author: Ian Caine

Date: Spring 2017

Abstract

This project explores the power of lines to tell stories. For architects, lines are elemental devices: they catalyze and structure our ability to describe space. But can they describe time and experience? The following case study explores this question in depth while tracking the historical expansion of suburban life in San Antonio, Texas. The research focuses on five roads, re-imagining them as a series of concentric timelines that stretch from the city’s historical center to its suburban periphery. To date the multi-disciplinary team—led by architect Ian Caine with collaboration from a historian and an urban geographer—has utilized three distinct media to represent the chronological growth of San Antonio: 1) a large two-dimensional timeline that the team exhibited in a museum gallery, 2) a video-based spatial-temporal narrative that simulated the experience of driving through the city, and 3) a web-based interactive timeline.1 This article establishes the merits of the first two approaches—which are both complete—before speculating about the potential of the web-based version to recast the timeline as a narrative device capable of illuminating the complex relationship between time, space and experience in the contemporary city.

Introduction

Over the past three years, our design team has experimented with three distinct conceptual approaches to build an urban timeline of San Antonio, Texas. With each progressive iteration, we tested a different medium, in an attempt to more fully represent the multifaceted reality of San Antonio’s suburban expansion. Taken separately, these three efforts provide critical insight into the individual capacities of various media to construct a spatial narrative. Collectively, they chronicle the progression of our thinking about the expansive potential that digital media possess to facilitate explorations of urban history. The project phases unfolded as follows:

Drawing the Line. The team began by crafting a 33-foot long by 9-foot high, two-dimensional graphic timeline tracking the expansion of a single road across parallel time and distance axes. The installation, titled Traveling on Fredericksburg Road: 120 Years in 12 Miles, also incorporated a nominal amount of digital media, using a monitor to display oral histories recorded from local residents and business owners.

Driving the Line. In the second iteration, the team produced a spatial-temporal narrative that explored a driver’s experience traveling on Fredericksburg Road. We assembled the narrative using footage taken from a dashboard-mounted camera, digital animations and a voice-over narrative.

Digitizing the Line. In the third and current iteration, the team is generating a web-based timeline that chronicles the suburban expansion of five of the largest automotive thoroughfares in San Antonio. Our digital tools include ArcGIS, a geographic information system that permits us to compile and analyze demographic and geographic data; and Data Driven Documents (D3), a JavaScript library that allows for the production of dynamic, interactive digital data visualizations in standard web browsers.

None of the design team had previous experience working in the digital geo-humanities. Therefore, the article describes our initial excursions into this promising and relatively uncharted intellectual landscape. During our transition from physical to digital mapping, we spent the most time engaging four critical conceptual issues:

Convergence of time and space. Perhaps our greatest challenge has been finding a way to establish an appropriate hierarchy of time, space and experience. Inevitably, one of the phenomena emerges as a dominant element, rendering the other two as mere derivatives. These conceptual tensions were likely intensified by our project’s intellectual genesis within the discipline of architecture, which historically privileges spatial relations above all others.

Ability of users to interact with the timeline. We continue to experiment with the parameters of the timeline’s interface. The challenge is one of narrative control, balancing the needs of the user with those of design authorship.

Ability to convey place. We are testing new media in an attempt to find one that transcends the simple representation of space. Our goal is to utilize one or a combination of formats that introduce experience, the critical but elusive prerequisite of establishing place [2].

Ability of the timeline to incorporate data. We continue to investigate the most effective way to incorporate data into the spatial and temporal structure of the timeline.

The team is now exploring these issues through a series of design prototypes for the web interface, several of which are discussed later in this article. Through this iterative process, the team is building a timeline that is more temporally precise, more spatially fluid and one that more fully leverages human experience to build a robust and nuanced narrative of suburban expansion in San Antonio.

*****

Conclusion

These discussions return us to our original question, which involved the capacity of digital technology to recast the timeline as an interactive device capable of representing the relationship between time, space and experience in the contemporary city. Digital technologies have clearly sharpened and expanded our work: establishing a more precise hybrid relationship between time and distance, increasing our ability to convey place through the addition of multi-media elements and allowing for the productive inclusion of data. Still, their use has also raised a number of theoretical questions, primarily related to the authority and transparency of the mapmaker’s voice and the optimal level of user interface. Clearly significant epistemological questions remain involving the extent to which a deep map itself delivers narrative content [32].

One thing that our work to date has confirmed, however, is the need for architects and urban geographers to generate new research methodologies capable of establishing relationships between the multiplicity of architectural, demographic and structural forces that comprise the contemporary city. As landscape architect Christophe Girot writes:

We know that the contemporary city is no longer the product of a single thought or plan, the vision of some prince, but rather the diffuse result of successive layers of decisions rarely having anything to do with each other [33].

Our research continues to use digital technology to lay bare these seemingly unrelated ‘layers’, banking on the capacity of these powerful new tools to make previously invisible relationship visible while providing deeper insight into the contemporary urban condition.

Notes

[2] Here we utilize Yi-Fu Tuan’s classic definition of place as space instilled with experience. See Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place: The perspective of experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977. 6–7.

[32] Stuart Dunn, Lesely kadish and Michael Pasquier, International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing 7.1–2 (2013), 194.

[33] Christophe Girot, ‘Vision in Motion,’ in Charles Waldheim, editor, Landscape Urbanism Reader. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006), 91.

Images: Edinburgh University Press, Xuhua Cheng, Ian Caine, Xuhua Cheng, remainder of the images by Ian Caine

SAN ANTONIO 360: THE RISE AND DECLINE OF THE CONCENTRIC CITY 1890-2010

Publication: Sustainability

Authors: Ian Caine, Rebecca Walter, Nathan Foote

Date: April 2017

Full Article: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/9/4/649

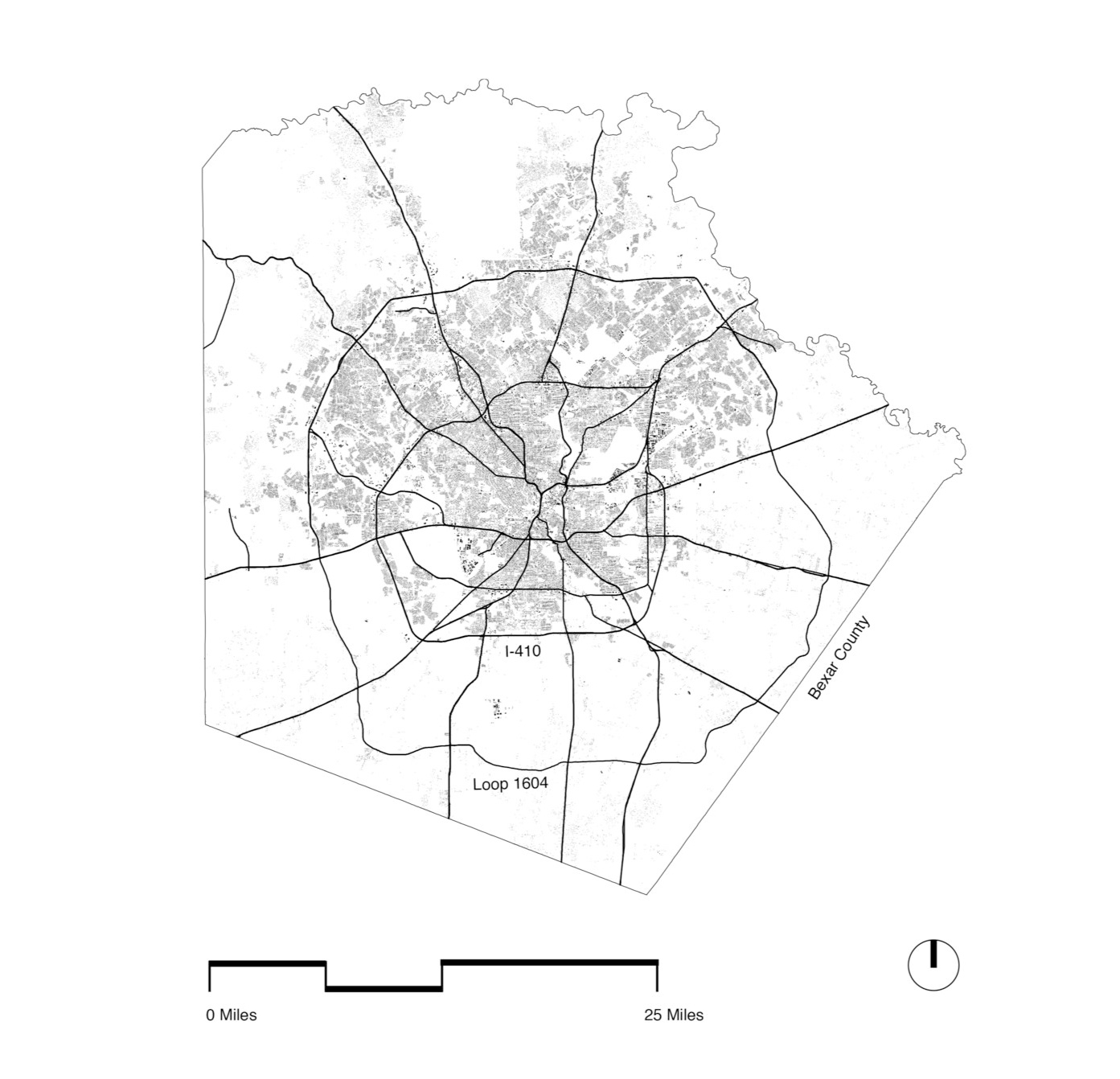

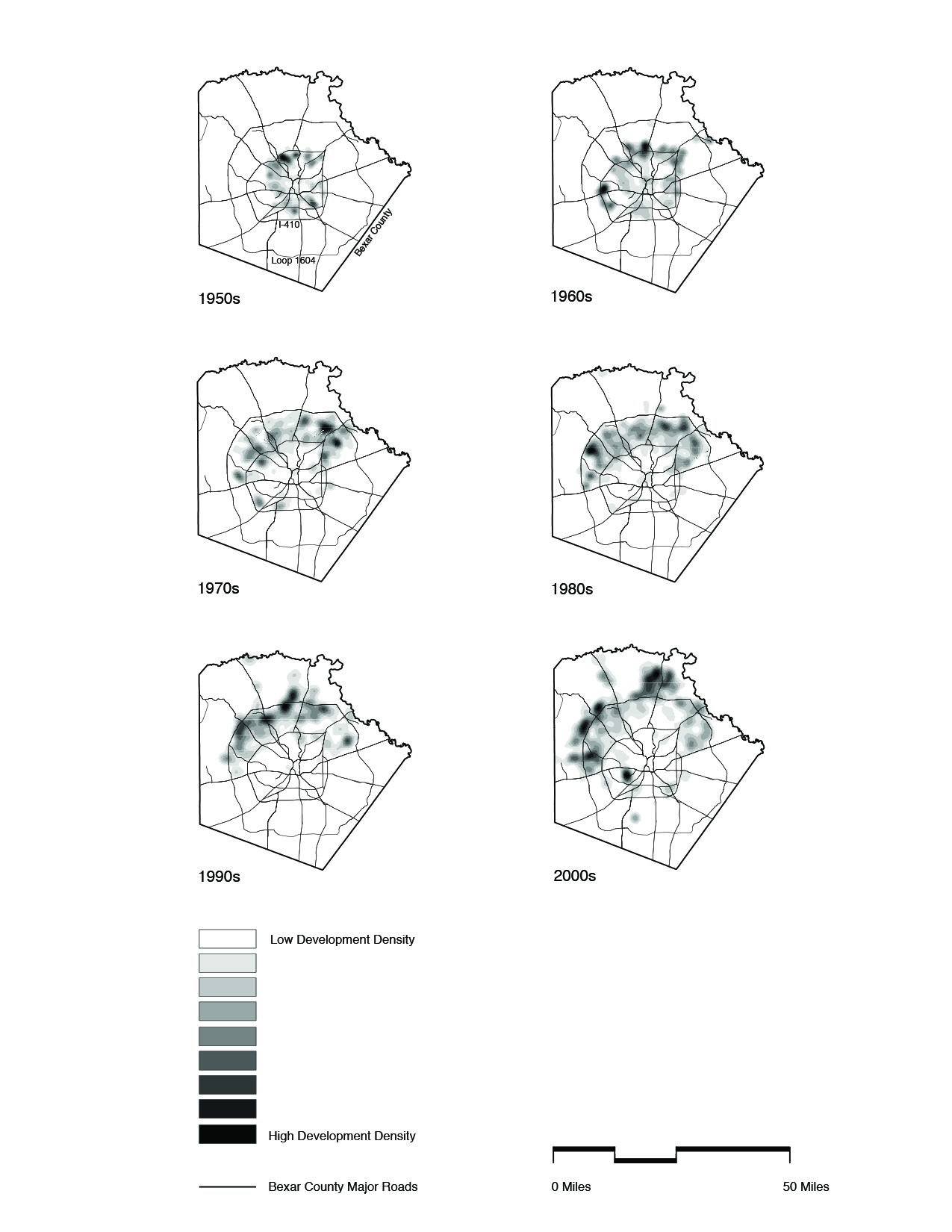

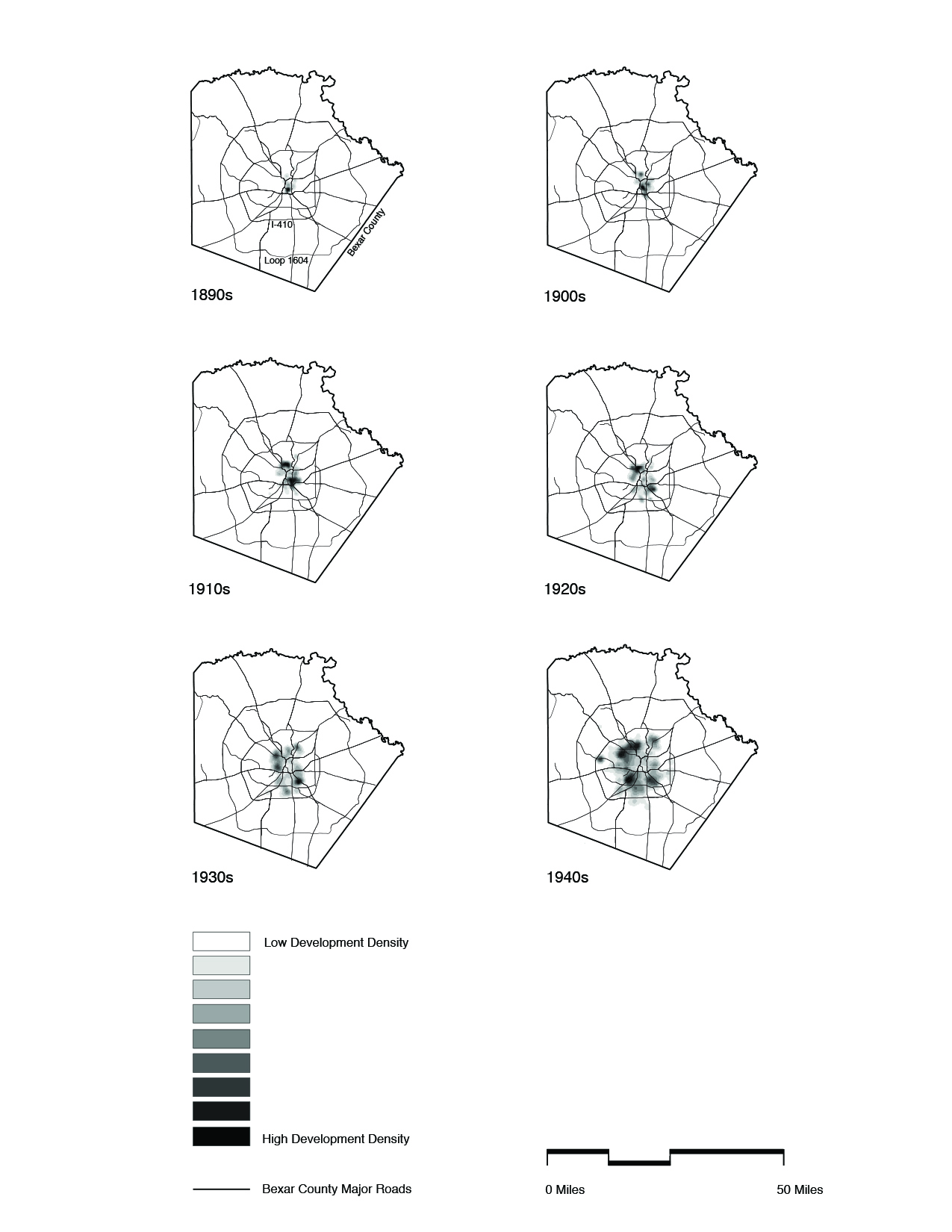

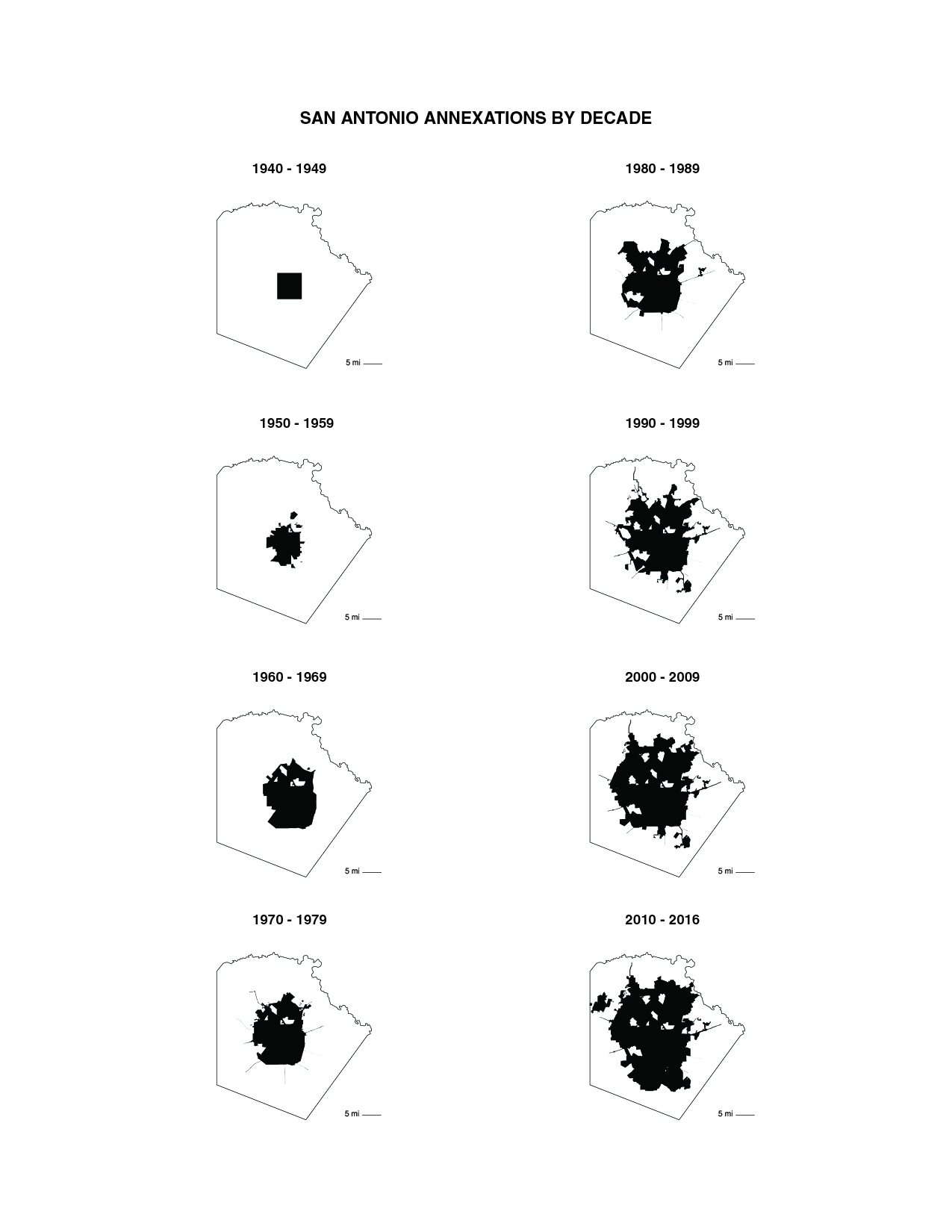

Abstract. This paper catalogs the suburban expansion of San Antonio, Texas by decade between the years 1890 and 2009, a time frame that saw the city reorganize its morphological structure four times. The city inhabited a 36-square mile grid until the late nineteenth century; expanded radially along streetcar lines during the early twentieth century; grew concentrically along automotive ring roads during the mid-twentieth century; and has assumed a polycentric organization within the past two decades. This research places San Antonio’s recent demographic and geographic boom into historical perspective, utilizing construction completions in host Bexar County to answer the following question: how did the form, location, and type of suburban growth shift over 120 years? The research reveals three trends: first, that historically concentric growth patterns began to assume a polycentric configuration in the late twentieth century; second, that patterns of centrifugal expansion began to accelerate dramatically during the same time period; and third, that the relative increase of multifamily completions has surpassed that of single-family completions in five of the last six decades. These findings suggest that the City of San Antonio, in order to establish a sustainable growth model, must prioritize the opportunities and constraints associated with polycentric suburban expansion.

*****

Discussion. The current research confirms several critical trends: first, since the year 2000 San Antonio’s urban development has become increasingly polycentric; second, the rate of centrifugal growth has increased dramatically since 1990; and, third, multifamily housing is playing an increasingly large role in defining the form and program of the metropolitan area. Collectively, these trends attest to San Antonio’s emergence as a polycentric metropolitan area, where the vast majority of growth is occurring beyond the limits of the traditional city.

While this observation does not distinguish San Antonio among Sunbelt cities, it does represent a bold reconceptualization of the metropolitan region. Prevailing public images of the Alamo City focus almost exclusively on downtown, highlighting the beautifully preserved Spanish colonial grid, Alamo, Riverwalk promenade, and Mission district. This image is magnified by the city’s impressive record of historic preservation, which became even more distinguished in 2015 with UNESCO’s inscription of the San Antonio Missions as World Heritage sites. San Antonio’s historic emphasis on the downtown core has driven tourism and urban policy for decades. Still, the data makes clear that halfway through the ‘Decade of Downtown’, relatively little of the city’s development is actually occurring downtown.

The results of this research in no way diminish the physical and cultural importance of San Antonio’s historic downtown and Missions. Rather, they question the relevance of a concentric growth model in light of persistently scattered development patterns that favor the periphery. Modarres [37] (p. 120) makes the argument that in order ‘to build a sustainable, polycentric or networked city, we need to re-think our notions of urbanism, urban planning, urban management, and development’. Increasingly, the planning community in San Antonio is taking up this challenge while recasting suburban development as something more than an unfortunate aberration.

The recently completed 2016 Comprehensive Plan successfully challenges dated concentric models that would privilege the historic downtown and central business district. The current plan forecasts that no fewer than thirteen distinct employment centers will be required to absorb the continuing economic boom [3]. This shift is noteworthy to the extent that it imagines the next San Antonio as a rapidly expanding, polycentric, decentralized landscape that will continue to resist geographic containment. Only by fully accepting this reality can San Antonio begin to generate sustainable growth policies that critically engage land use, transportation, open space conservation, and aquifer preservation.

The Comprehensive Plan’s decision to abandon a concentric model in favor of a polycentric one seems particularly appropriate given the lack of political will to implement growth restrictions, such as the ones that curtailed geographic expansion in Portland, Oregon [38]. If policy-makers truly intend to guide growth towards a more sustainable outcome, they must assertively engage the suburban periphery. This will necessitate new approaches to land development that incentivize urban infill and density, not just in downtown and inner-ring locations but also in post-war suburbs and even at the emerging edge. This approach will require the development of new suburban prototypes that can increase densities and mix uses without the benefit of traditional urban morphologies. Such an approach may also begin to challenge the conventional wisdom that emphasizes the importance of leveraging existing infrastructures, particularly those with physical proximity to the historical center. While the logic of this position is clear, it does not account for the fact that, historically, most development has occurred at the periphery of the city, a zone that has moved continuously farther from the historical center since 1890 (Table 2, Figure 3).

In a span of several decades, San Antonio has emerged as the fastest growing major city in the U.S., easily outpacing Phoenix and San Diego, its two closest competitors [39]. This seismic shift is placing unprecedented demand on local ecologies and infrastructures. It is also stretching San Antonio’s civic imagination, requiring policy-makers and residents to confront the unfamiliar terms of contemporary urbanism while relinquishing historic notions of a concentric city that lost currency after the Second World War.

As San Antonio scrambles to accommodate this growth, it must aspire to urban models that expand the physical and conceptual parameters of the Spanish colonial grid. Within this context, the theoretical framework of New Suburbanism becomes relevant, infusing the discourse with new ideas while avoiding the lament that often accompanies discussions of suburban growth. While efforts to preserve downtown and infill the central city remain vital, the next chapter in San Antonio’s story is being written at the city’s periphery and beyond. As San Antonio sets course for the next twenty-five years, it must continue to explore a more dynamic relationship with this emerging geography, conceiving a future sufficiently complex to befit the city’s celebrated past.

Notes

[3] MIG in Association with Economic & Planning Systems, Inc.; WSP; Parsons Brinkerhoff; Ximenes & Associates, Inc. City of San Antonio: Comprehensive Plan. San Antonio, TX, USA, 2016.

[37] Modarres, A.; Kirby, A. Viewpoint: The suburban question: notes for a research program. Cities 2010, 27, 114–121.

[38] Catenaccio, G. Urban growth boundaries: Two American examples. Projections 10: Des. Growth Chang. 2011, 10, 13–30.

[39] Gonzales, F. San Antonio: Demographic Distribution and Change 2000 to 2010.

Images: Ian Caine and Rebecca Walter

Municipal Annexation as a Mechanism for Suburban Expansion in San Antonio, Texas 1939-2014

Publication: ARCC National Conference Proceedings: Architecture of Complexity: Design, Systems, Society and Environment

Authors: Ian Caine, Jerry Gonzalez, Rebecca Walter

Date: 2017

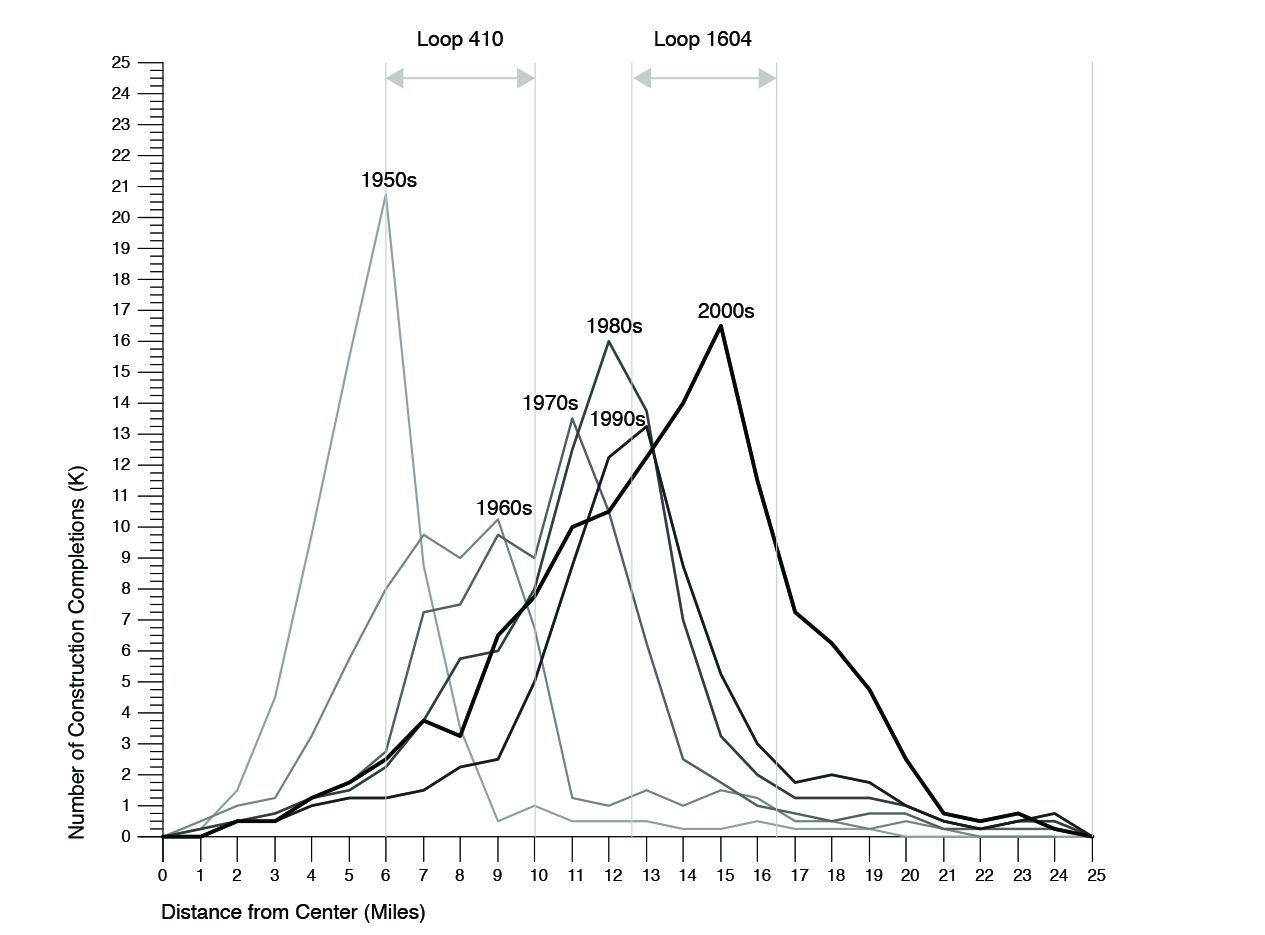

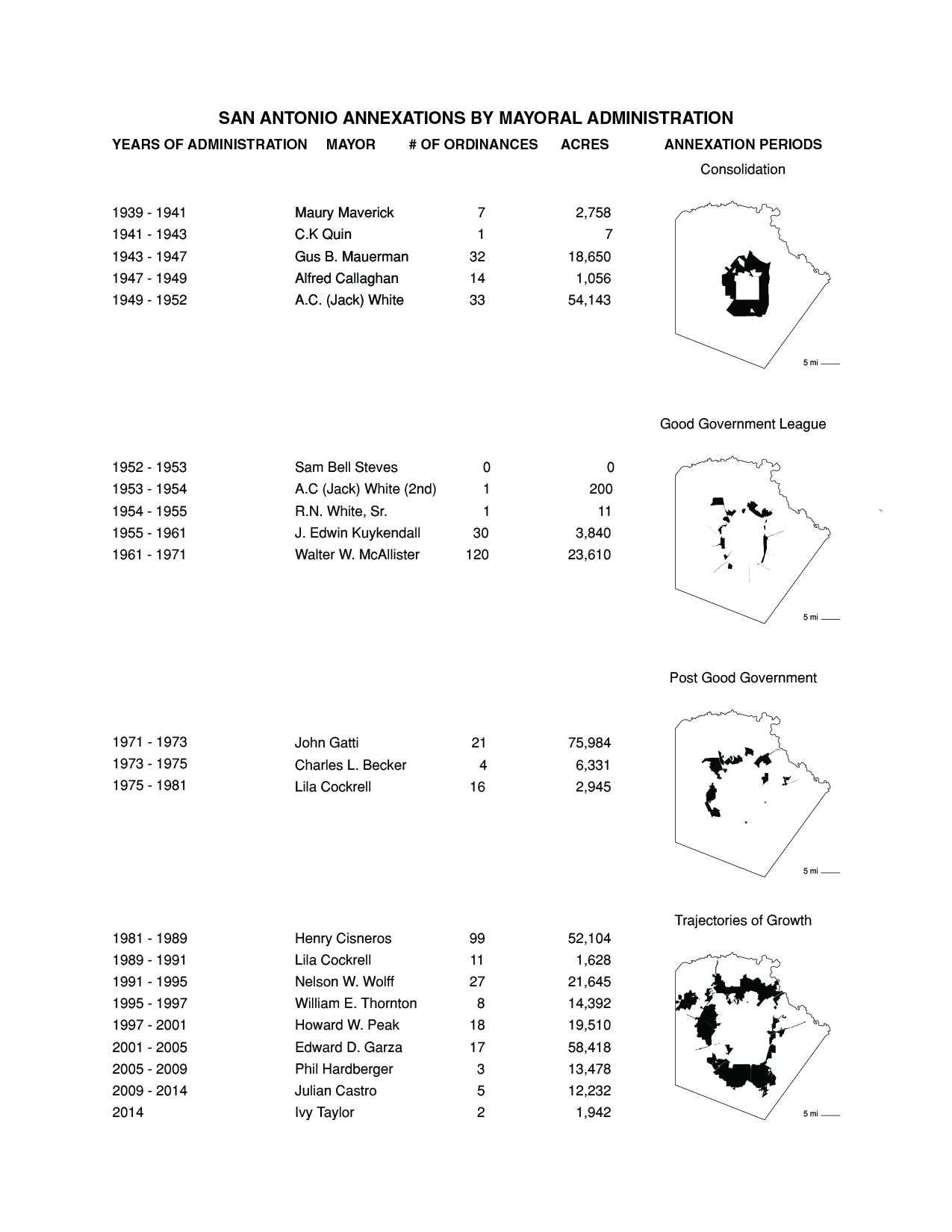

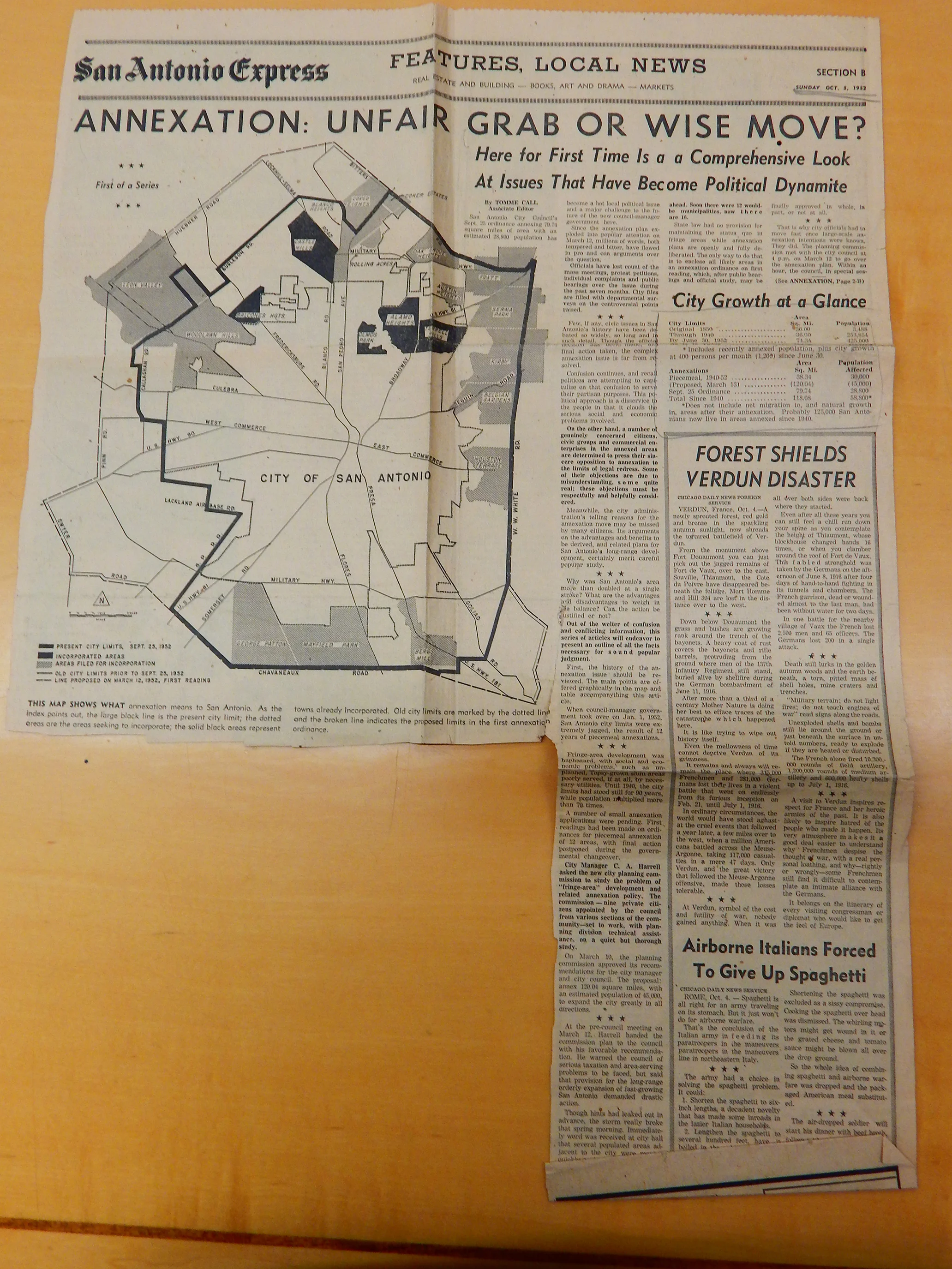

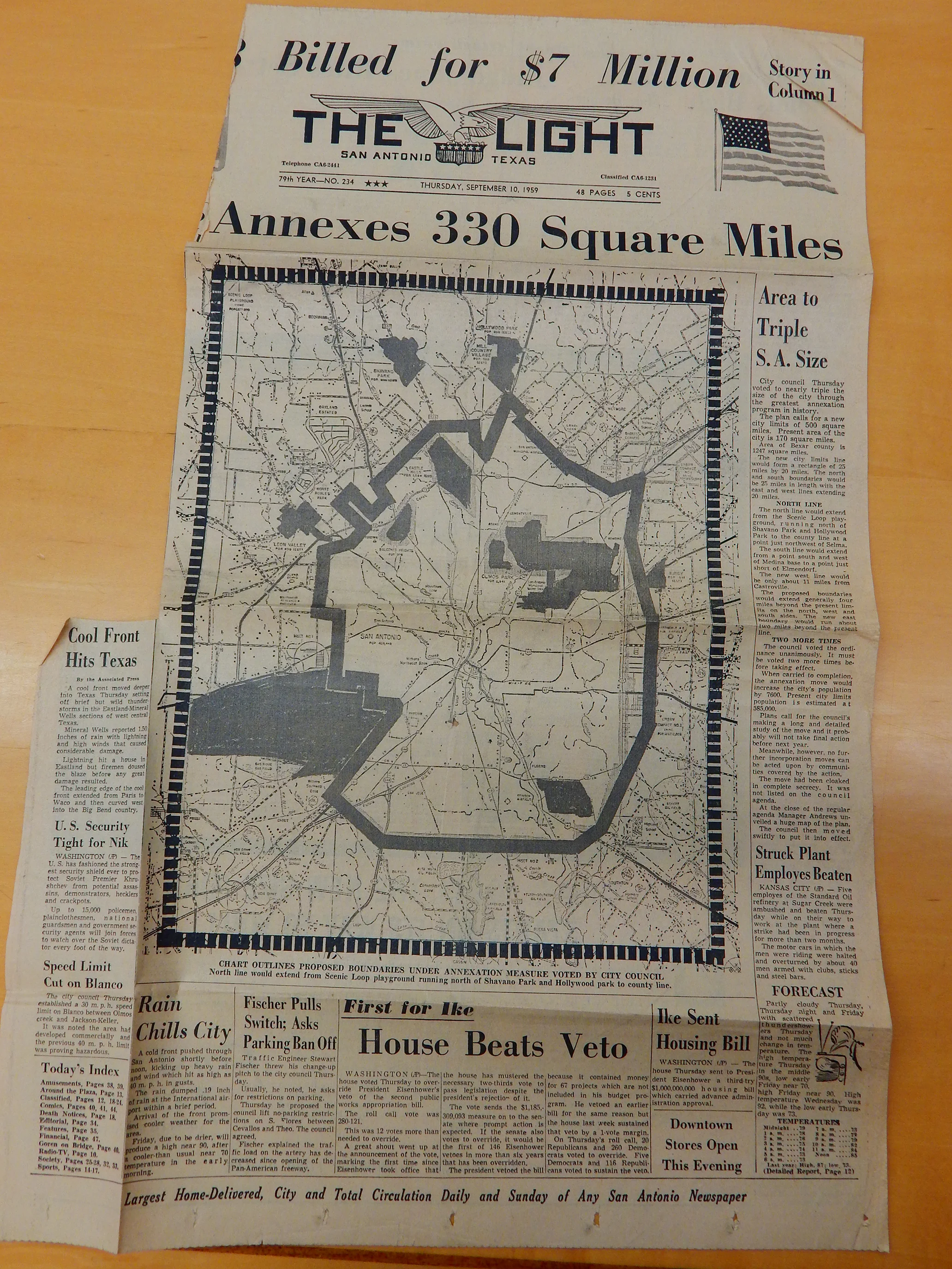

Abstract. This paper examines the history of municipal annexation as a mechanism for suburban expansion in San Antonio, Texas between 1939 and 2014. Annexation, which permits municipalities to enlarge jurisdictional boundaries by absorbing adjacent, unincorporated areas, emerged as a powerful governmental apparatus to grow Sunbelt cities across the postwar United States. Political elites in San Antonio began leveraging annexation with remarkable efficiency after World War II and continue the practice today. During the period under study, the city council executed 461 annexations and boundary adjustments, adding 497 square miles to the metropolitan footprint [1]. The same time frame saw San Antonio grow to become the seventh most populous city in the United States, adding 430,000 people in the last decade alone, with another 1.1 million expected by 2040 [2]. The continued use of municipal annexation as a way to grow the city has generated a wide array of responses among citizenry, ranging from strong support within development communities eager to access emerging markets, to opposition from historically disenfranchised neighborhoods where people contend that annexation further consolidates resources in middle- and upper-income areas of the city. This paper examines the historical roots of such positions in an attempt to clarify today’s contentious discourse on annexation in San Antonio.

*****

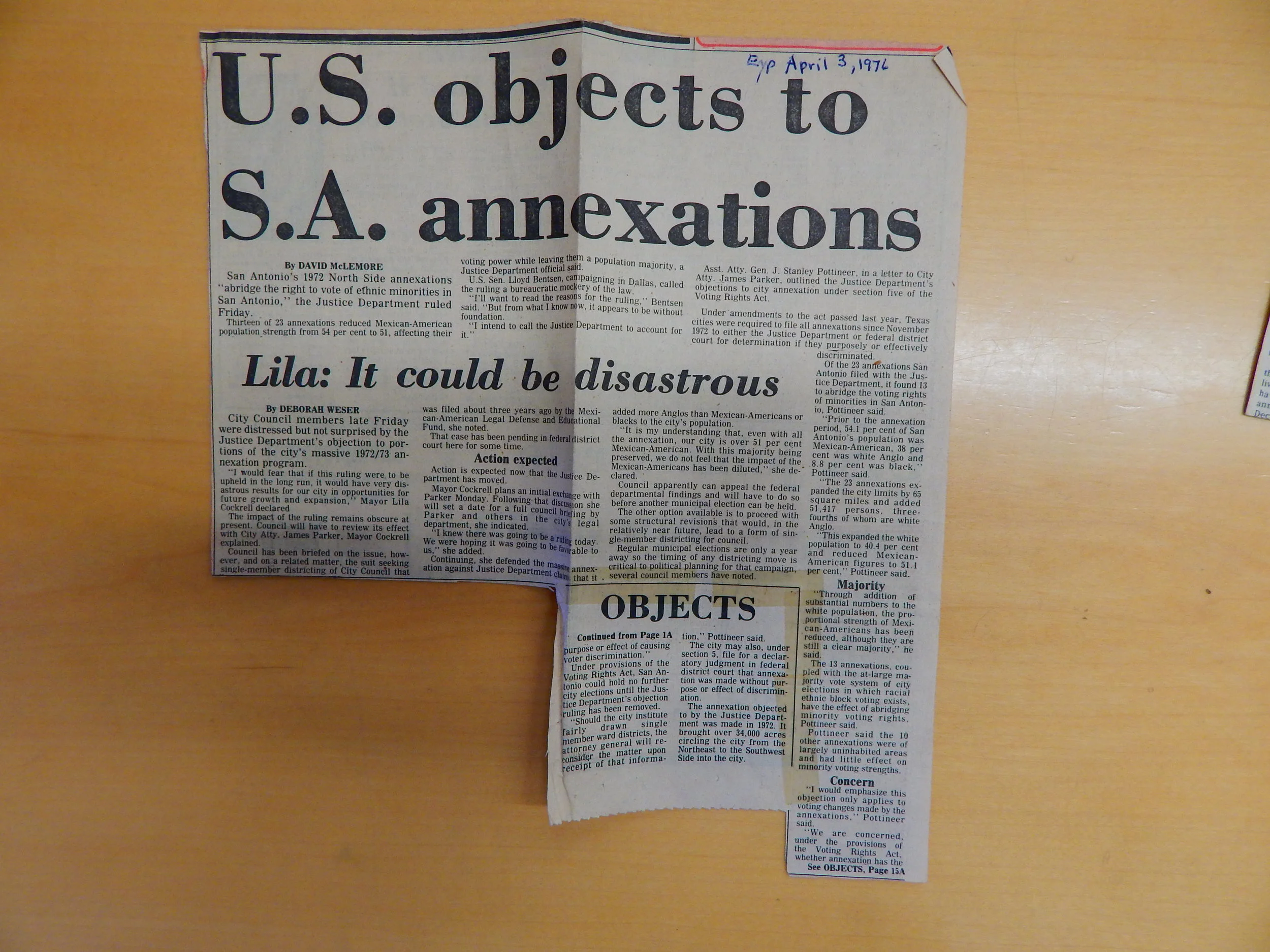

Conclusion. The history of annexation in San Antonio reveals that, where urban growth was concerned, the enduring competition between multiple, often diverging political interests produced a consistent outcome: the expansion of municipal boundaries. The city’s 461 annexations and boundary adjustments since 1940 testify to the formative role that annexation played in the political and geographic growth of the city [1]. This is not to say that proponents of annexation were motivated by singular ambitions, or that the practice has yielded a predictable result. To the contrary, the practice of annexation has generated a wide variety of impacts and opinions: what began as a way for municipal government to consolidate tax revenue has become a rallying cry for anti-tax groups; where progressive elites tout annexation as a tool for coordinated growth, proponents of localism instead see a threat to political autonomy; while the San Antonio business community enthusiastically leverages annexation to expand economic opportunity, disenfranchised groups claim that it simply allows political and economic elites to consolidate power; and while some peripheral communities hold the hope that annexation can help them acquire increased political access and municipal services, others see it as an empty promise, guaranteed only to raise taxes.

Nevertheless, we can make several critical observations about the historical impact of annexation on San Antonio’s urban growth. First, while elites used the mechanism for decades to consolidate and extend their own political power, the Charter reform of the 1970s unquestionably spread the benefits of annexation more evenly across city populations. Today, City Council and council districts represent voices that decades ago did not enjoy access to power. Still, the larger impact of the council system turned out to be more political than economic, as the vast majority of economic growth continues to appear on the north side of the city, which is disproportionately Anglo.

Second, the practice of annexation allowed San Antonio’s city government to capture a growing regional population and tax base that would have otherwise been lost to neighboring municipalities. It is no accident that San Antonio today boasts the seventh largest population among U.S. cities, despite its location within the twenty-fifth largest metropolitan statistical area in the country [3]. San Antonio’s standing as one of the ten most populous cities in the U.S. continues to enhance the city’s national profile, helping it to attract new businesses and investment—a fact not lost on Mayor Cockrell over four decades ago. Annexation additionally preventedthe political fragmentation seen in so many other U.S. cities, allowing the city to maintain a relatively cohesive—if often contentious—public discourse.

Third, the practice of annexation in San Antonio accelerated the centrifugal expansion of population and investment. Massive decentralization resulted in the dispersion of industrial and residential program away from the city center and towards the suburban periphery. With the pattern of northward growth firmly established by the 1970s, annexation did more than stretch the political boundaries of the city. The integration of existing and self-sustaining neighborhoods exacerbated suburban isolation and increased overall wariness of centralized planning processes.

Finally, despite the positive overall impact of the city council system, the patience of working-class San Antonians wore thin as their communities continued to suffer infrastructural and representational neglect. In this regard, annexation intensified tensions up and down the class spectrum, and across racial lines. When the Justice Department found the city in violation of the 1975 amendments to the Civil Rights Act that guaranteed representative government, the city was forced to redesign its charter. Despite such signal achievements, the business of growth persists and is accelerating. Slow-growth NIMBYism has since become a steady companion to municipal expansion. This tension continues to produce fierce public debates over the limits of homeownership, environmental degradation, class privilege, and the integration of underrepresented people into civic life.

Against this complex and evolving backdrop, annexation continues to define spatial politics in San Antonio today. The long history of annexation has resulted in a widespread—at times fatalistic--acceptance of the practice. As local Council member Mike Gallagher recently concluded, “[w]e’re going to grow, no matter what. Either we are going to control it or someone else will [4].” So it is that the residents of San Antonio, like so many other Sunbelt denizens, can expect to contend with the continued costs and benefits of municipal annexation in the decades to come.

*****

Notes

[1] “List of Annexation Ordinances,” City of San Antonio Department of Planning and Community Development

[2] Robert Rivard, “City Planning for San Antonio Growth Bomb,” Rivard Report, October 16, 2016 (accessed April 1, 2016).

[3] “Metropolitan and micropolitan statistical area population and estimated components of change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016 (CBSA-EST2016-alldata),” United States Census Bureau

[4] Edmond Ortiz, “City Staff Makes the Case for Annexation Plan,” Rivard Report, 1 October 2015.

Images: Integrated Technology in Architecture Consortium (cover), Ian Caine and Rebecca Walter, Ian Caine and Rebecca Walter, San Antonio Express, San Antonio Light, San Antonio Light, San Antonio Light

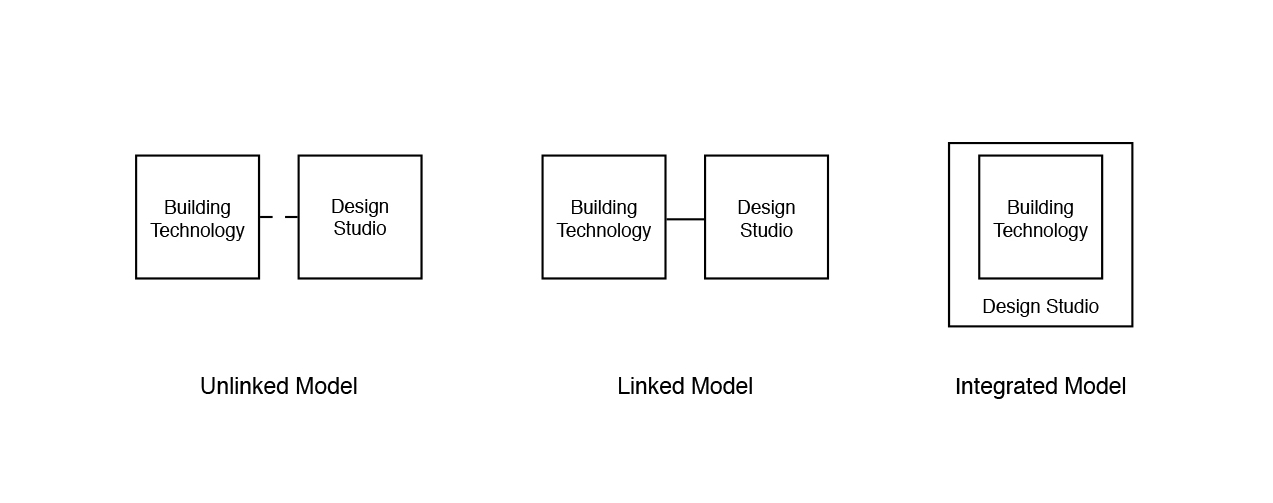

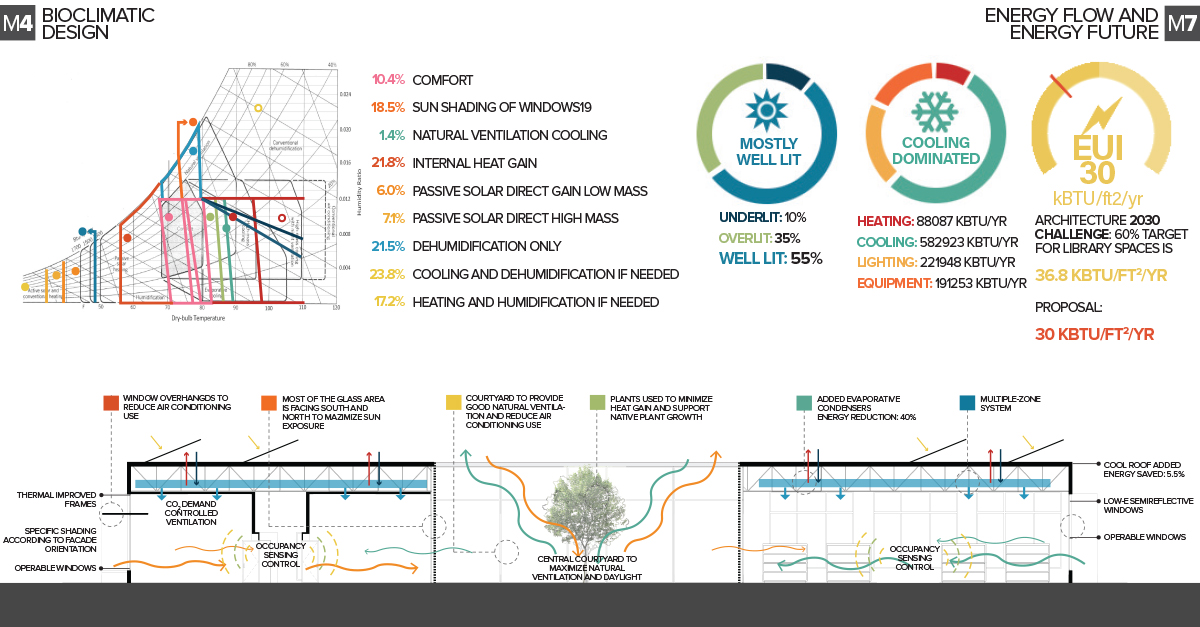

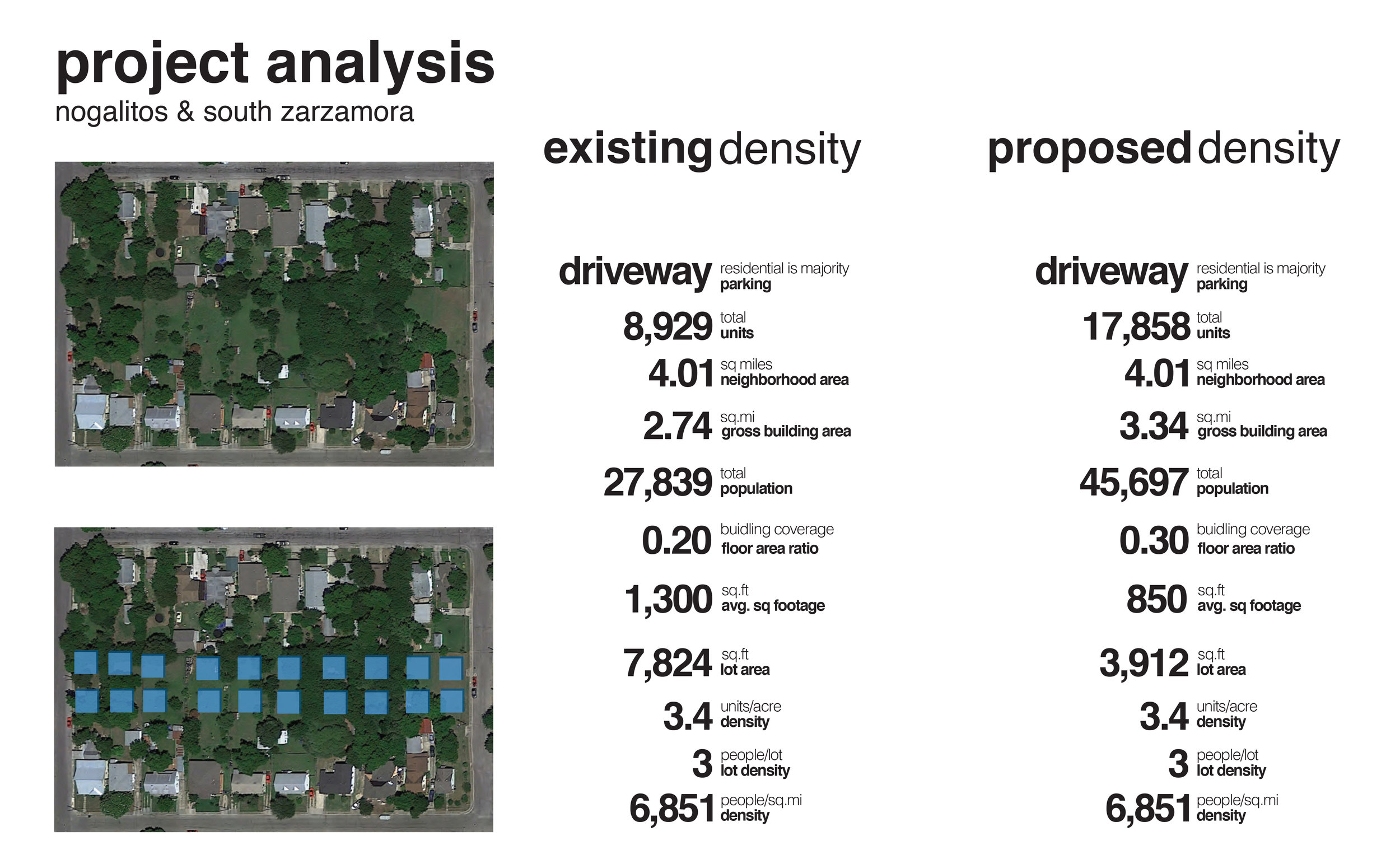

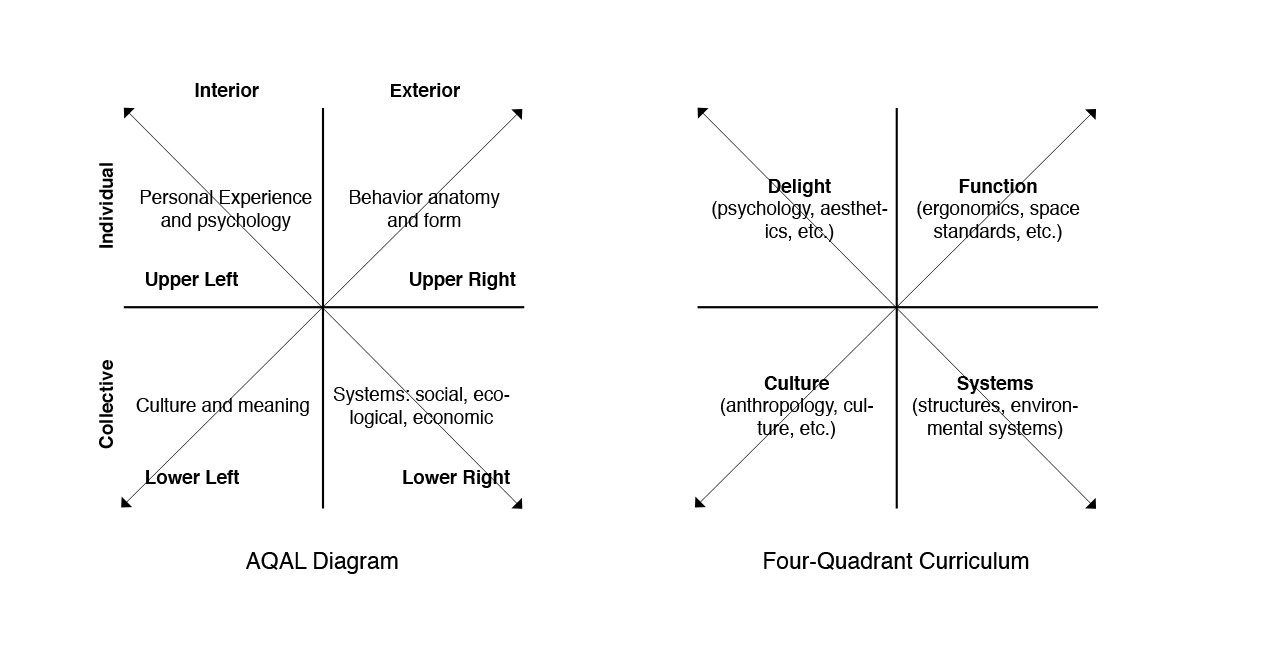

Applying Performative Design Tools in the Academic Design Studio: An Integrated Pedagogical Approach

Publication: ARCC National Conference Proceedings: Architecture of Complexity: Design, Systems, Society and Environment

Authors: Ian Caine, Rahman Azari

Date: 2017

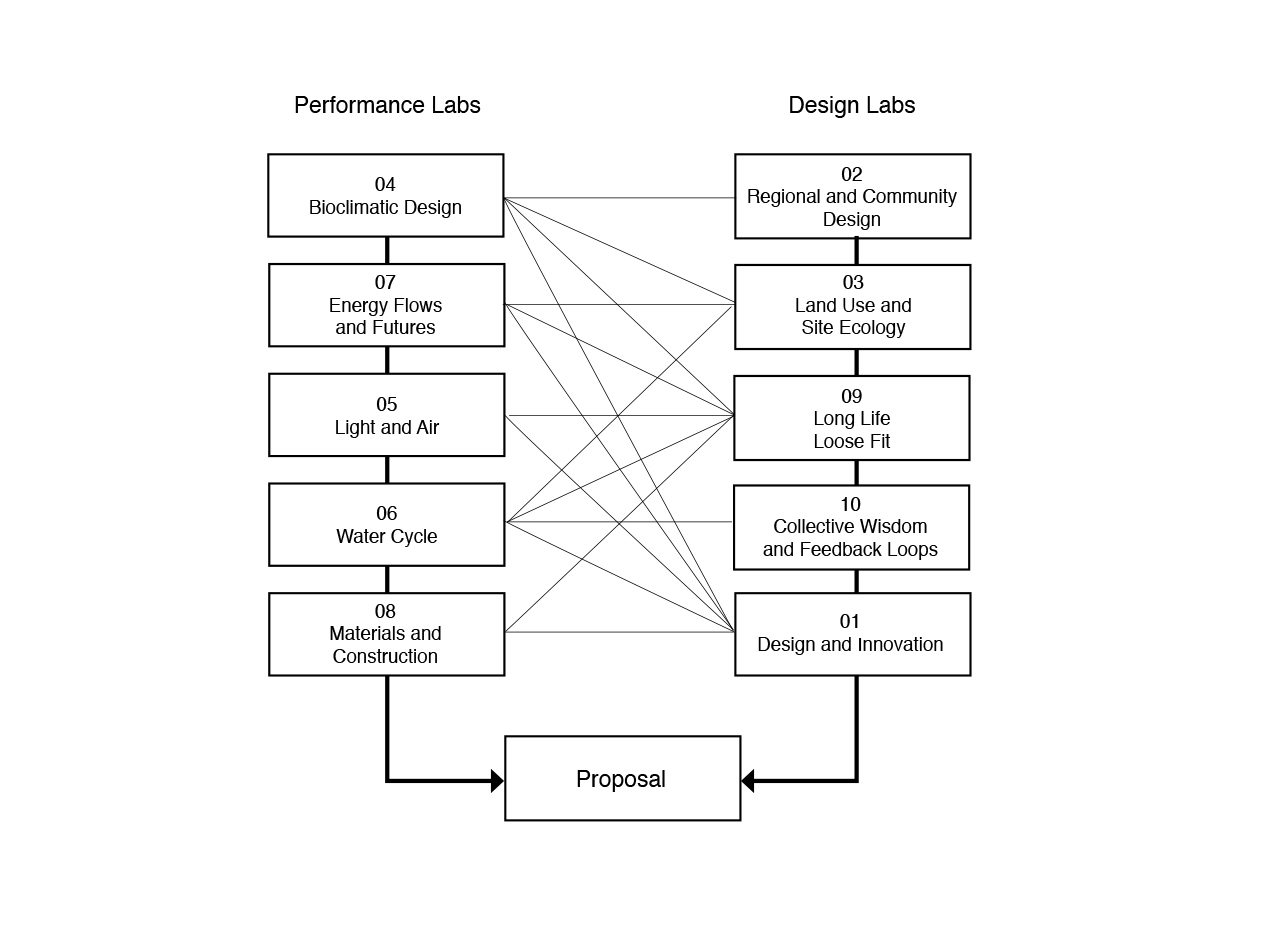

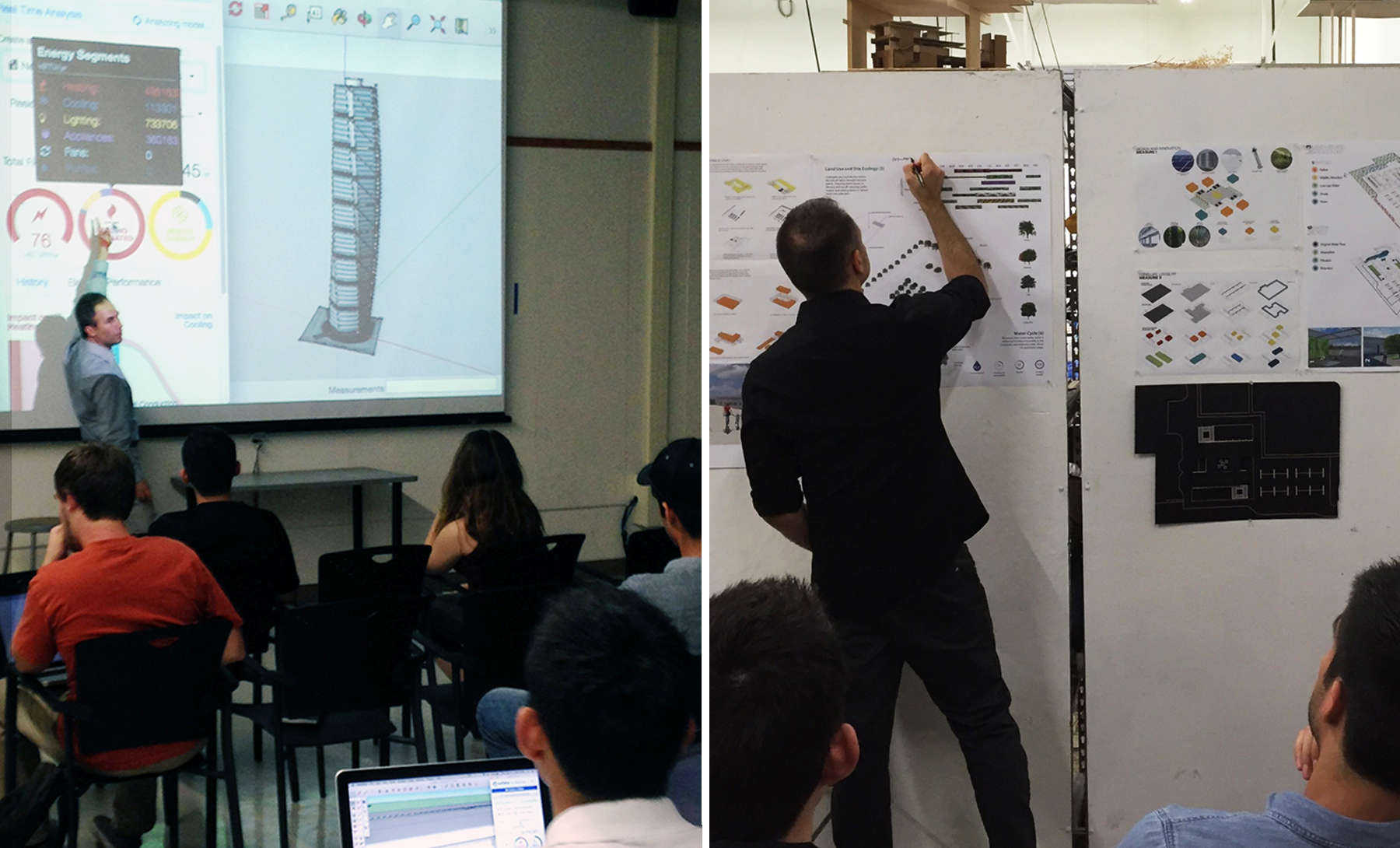

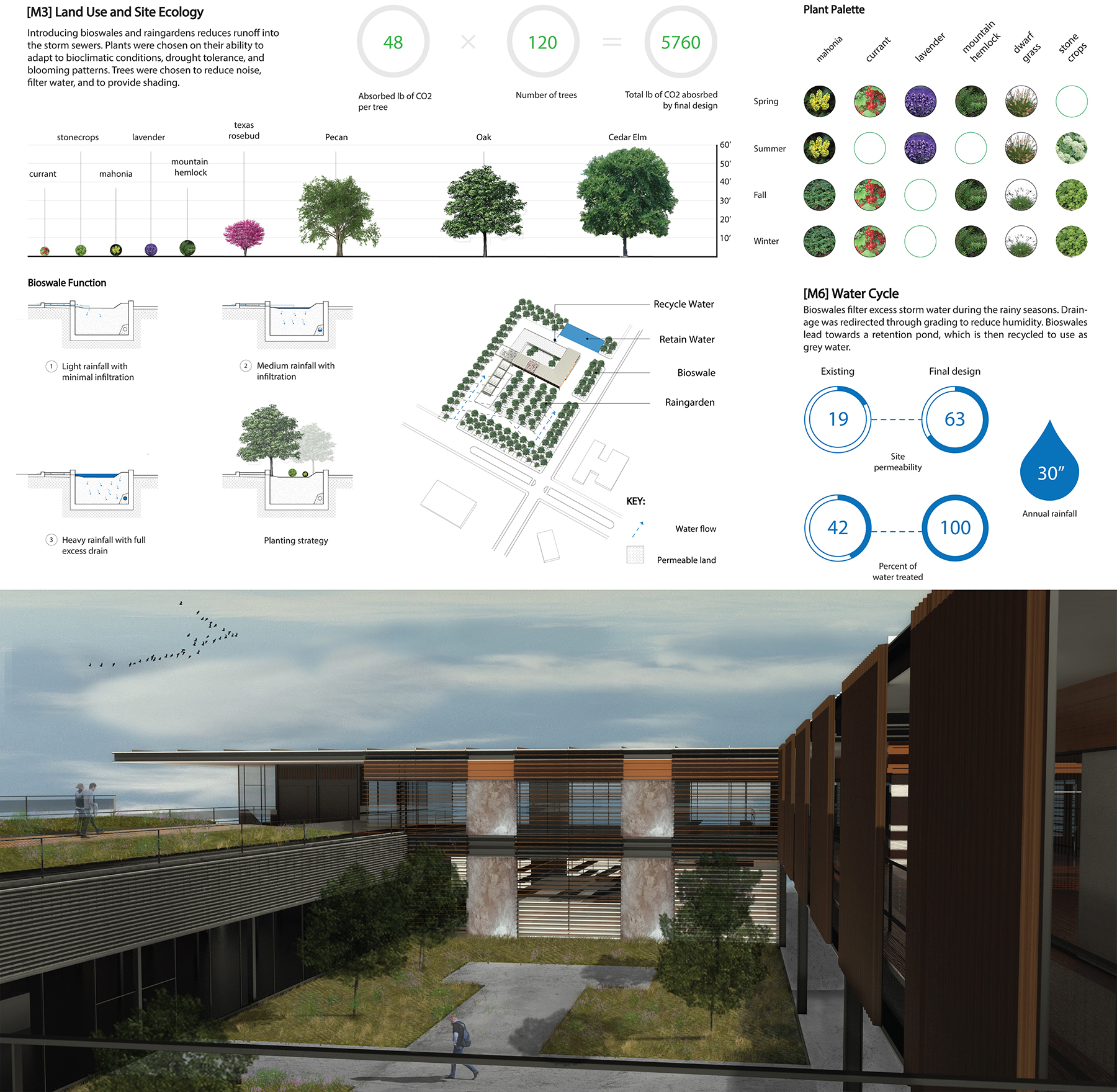

Abstract. This paper describes a third- and fourth-year pilot design studio at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA). Two instructors—one with expertise in building performance and the other in architectural design—implemented a systems-based approach to teaching undergraduate design studio that allowed students to explore the oft-misunderstood relationship between architectural performance and form. The instructorsintegrated advanced performance modeling into the design curriculum, restructuring the studio around 10 parallel and interactive lab sequences: 5 covering topics specifically related to building performance and 5 covering general design topics. The reconfigured studio required participants to pursue issues of sustainability and design in parallel, allowing students to leverage building performance as a form generator, not a technical overlay. Both iterations of the studio produced a winning entry in the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Committee on Technology and the Environment (COTE) Top Ten for Students Competition, which recognizes ten winners annually from a national pool of entries.

Introduction. The negative impacts of climate change present an existential concern for architects, as the built environment is a major contributor to the global environmental crisis. The severity of this crisis means that architects have a disciplinary obligation to accelerate the design and construction of carbon-neutral and carbon-positive buildings. Within the professional realm, architects are meeting this challenge, channeling their efforts through programs like the United States Green Building Council’s (USGBC) Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), begun in 1994,and the Architecture 2030 Challenge, begun in 2006. Both are widely accepted standards within the industry.

The response from the academy to date has been less clear. While theNational Architectural Accrediting Board(NAAB) maintains significant curricular requirementsrelated to environmentally sustainability and building performance, most schools have yet to integrate this critical material into traditional design studios. This paper describes a pilot studio curriculum at the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) that recasts the architectural design studio as a multi-disciplinary, systemic undertaking, one that considers the potentially dynamic interaction between issues of building performance and architectural form in the design studio. The two studio instructors—one with a background in environmental systems and the other in architectural design—initiated a curricular feedback loop, prompting students to engage a continuous dialogue between issues of building analysis and design. In this regard, thepilot course addressed a perceived curricular shortcoming, embedding issues of ecological literacy and performance metrics into a third- and fourth-year undergraduate design studio.

The studios fulfilled multiple learning objectives, seeking to

advance the design of a carbon-neutral built environment in accordance with the Architecture 2030 Challenge.

embed issues of ecological literacy into a traditional studio setting

create a critical feedback loop between issues of building performance and design

embed advanced performance modeling and metrics into a traditional studio setting

provide students with the opportunity to enter an international design competition

explore contemporary and competing theories of suburban design

develop new housing typologies that correspond to the suburban condition in South Texas

To date the instructors have implemented this curriculum twice, first during the fall semester of 2015 and again in the fall of 2016. Both iterations of the studio focused on programs related to the geographic and demographic expansion of San Antonio, Texas, one of the fastest growing cities in the United States. 1.1 million people will move to San Antonio in the next 25 years, a demographic influx that will bring the population of the city from 1.4 million to 2.5 by 2040. This rapid expansion will require the city to add 500,000 new jobs and 500,00 new units of housing, a significant challenge in a city that already added 430,00 people in the last decade [1].

The first iteration of the studio called for the adaptive reuse of a commercial big box, the most common and mundane of suburban building typologies. Students recast a prototypical Walmart Neighborhood Market in San Antonio as a neighborhood branch library, taking advantage of the typology’s most compelling traits: ubiquity, obsolescence, low-cost and flexibility. The second studio generated new typologies for suburban infill housing, considering the optimal location, design, and construction of these units.

In both cases, the instructors adopted the structure of the AIA Committee on Technology and the Environment (COTE) Top Ten for Students Competition. The AIA COTE Top Ten Competition required students to simultaneously generate formal and environmental responses to issues of innovation, regional design, land use and site ecology, bioclimatic design, light and air, water cycle, energy, materials, adaptability, and feedback loops.

[1] Robert Rivard, “City Planning for San Antonio Growth Bomb,” Rivard Report. August 29, 2014.

Images: Integrated Technology in Architecture Consortium (cover), Ian Caine and Rahman Azari, Ian Caine and Rahman Azari, Ian Caine and Rahman Azari, Reyes Fernandez and Carmelo Pereira, Elsa Deleon, Adriana Lintz and Veronica Rodriguez, Ian Caine and Rahman Azari (via Peter Buchanan/left and Ken Wilber/right)

SUSTAINING SUBURBIA: EXPLORING THE POLICIES, SYSTEMS, AND FORMS OF GROWTH

Publication: Sustainability (Special Issue)

Guest Editors: Ian Caine, Rebecca Walter

Date: January 2018

Special Issue Information. The impulse to decentralize has always existed as a logical response to the limitations of the spatially contained city. Historically, it fueled the creation of suburbs, which in turn provided an invaluable mechanism to accommodate people and programs that did not fit conveniently within the enclosed city. Suburbs appear across a range of cultures, spanning the ancient cities of Ur and Babylon, classical Rome, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century London, and nineteenth-century New York [1]. During the second half of the twentieth century, the cumulative impact of the automobile catalyzed an unprecedented dispersion of population away from historical urban centers and towards the suburban periphery. This trend, seen most acutely in the United States, provoked a spirited and sustained critique that begins with Lewis Mumford and endures today in the wide-ranging efforts of the Congress of New Urbanism. This robust discourse, which focuses on the well-established shortcomings of post-war suburbs, has nonetheless done little to stem the continued proliferation of these environments throughout the world.

Recently, a series of counter-narratives have emerged from a variety of sources that include authors Joel Kotkin, Robert Bruegmann and architect Judith De Jong. These arguments, which might be broadly grouped under the rubric of “New Suburbanism”, are united by two characteristics: First, a rejection of the premise that suburban processes are inherently problematic; and second, a willingness to engage suburban models as a legitimate and even desirable strategy for growth.

This Special Issue seeks to advance the evolving suburban discourse by addressing two fundamental questions:

To what extent are the policies, systems and forms of suburban development sustainable? The term sustainable in this context is understood to mean the effective and long-term maintenance of environmental, spatial, financial and social systems.

If we assume that suburban processes and forms will continue to proliferate, what critical interventions or evolutions will be required to ensure that they develop on a sustainable trajectory?

The Special Issue invites submissions that address one or both of these questions, either directly or indirectly, while pursuing one or more of the following topics:

Policy. The Special Issue will explore political structures that facilitate the process of suburbanization. Relevant inquiries might concentrate on the local scale, examining issues like zoning regulations or development practices; at the regional scale, exploring topics such as transportation or environmental policy; or at the national scale, investigating federal instruments that drive the production of suburbia such as housing or banking regulations.

Systems. The Special Issue will explore the larger networks within which the production of suburban fabric occurs. Potential topics could include ecological, infrastructural, financial or social systems.

Form. The Special Issue will examine the three-dimensional realization of suburban fabric. Relevant topics here are broad and might include shifting street and block patterns, emerging housing typologies, architectural strategies for infill development, or the changing spatial character of civic life.

The editors specifically welcome submissions that advance new theoretical frameworks, test innovative research methodologies, and develop empirical case-studies.

Notes

[1] Bruegmann, R. Sprawl: A Compact History; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005.